Have you ever felt the urge to start fresh, to shed the old and reinvent yourself in a way that allows your true self to shine? Craig Mod did just that when he left his working-class roots at 19 to immerse himself in the rich tapestry of Japan. Speaking little of the language, he embarked on a journey of self-discovery through art, music, writing, and publishing.

But it was the long walking pilgrimages, sometimes spanning 30-60 days, that remade him from the inside out. In this captivating conversation, Craig shares how committing to these extended walks allowed him to disconnect from distraction and tune into life’s riches. You’ll learn his insights on choosing fullness over fleeting pleasures and why limiting beliefs imposed by wealth and privilege shattered his reality, spurring a total reboot.

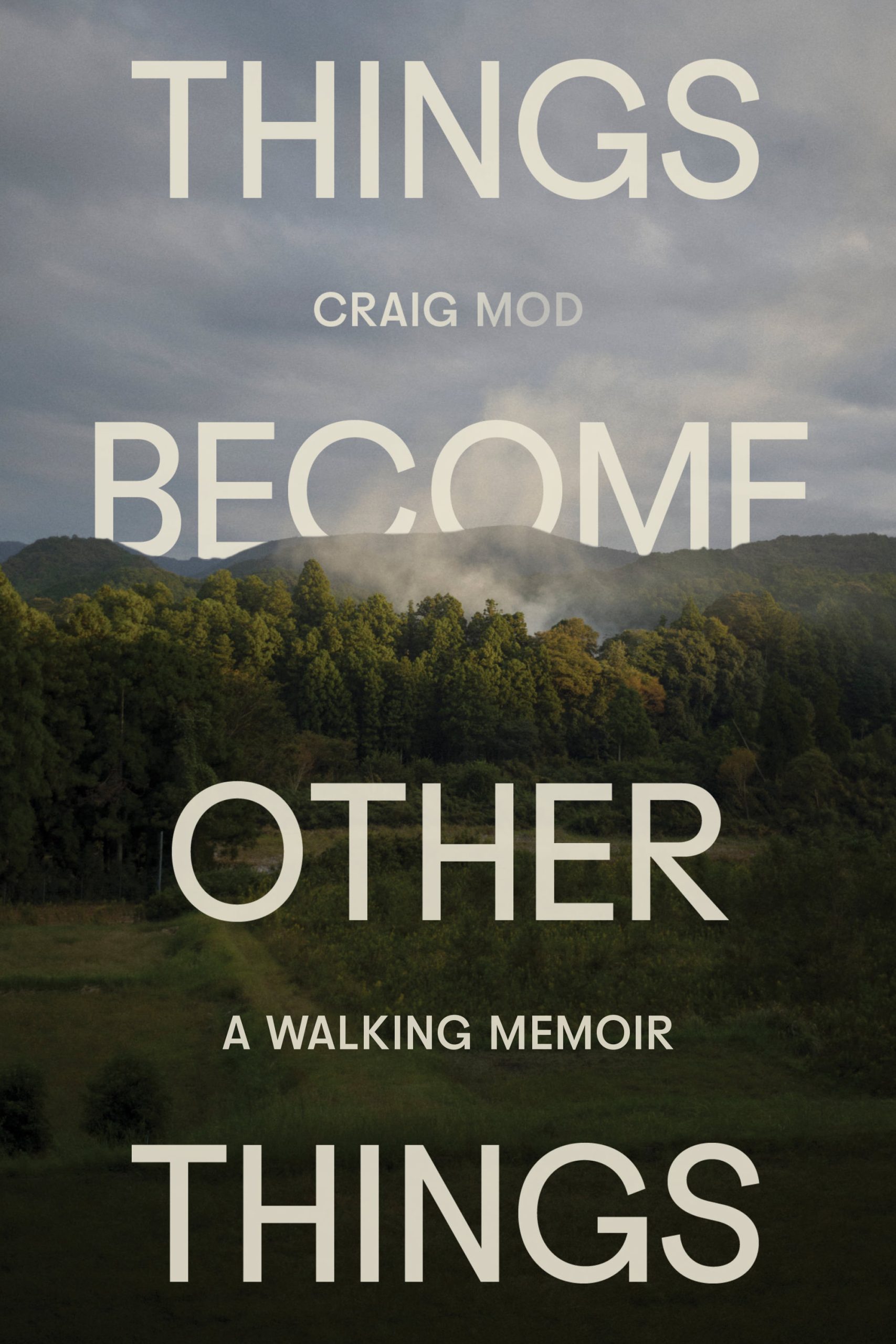

Weaving his unlikely path into the intimate letter that became his critically-acclaimed book Things Become Other Things, Craig’s story will inspire you to question every excuse for not living with unbridled expression. Get ready to rethink what’s possible when you honor your authentic self and share that gift with the world.

If you’ve ever yearned for a life of deeper meaning and adventure, this profound conversation will fill you with wonder at the extraordinary that awaits when you take that first courageous step.

You can find Craig at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Seth Godin about challenging conventional paths and thinking differently as an artist or entrepreneur.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:00] So have you ever felt like you just needed to kind of leave the life that you’ve been living? In order to create a clean slate that you need to live the life you yearn for, and maybe to be able to shed the old, stifled you, and reinvent yourself, or more accurately, reclaim the version of you that’s been kind of hiding inside for years. That is exactly what my guest today did. Craig Mod grew up in a working class town in New England, but something inside drew him across the world to Japan at just 19 years old, speaking very little of the language he wanted to, in his words, erase his old self and start fresh where nobody knew him or his story or his history. With no real plan and barely any language skills, he immersed himself in art and music and writing and eventually publishing and book making. And also along the way he started these long walking pilgrimages, like 30, 45, 60 days, that remade him from the inside out, and Craig eventually landed in what he describes as a six mat tatami room in Tokyo, which is like six yoga mats large, embracing a pretty minimalist lifestyle to maximize creative and financial independence. And that really set the stage for a breathtaking career as an author and artist, artisanal bookmaker and adventurer. And it’s all supported by this global community of thousands of patrons now who follow along with his journeys and line up to scoop up his books, selling out limited editions within hours of publication. In his latest book, the critically acclaimed Things Become Other Things, Craig weaves this unlikely journey into an intimate letter to a childhood friend while sharing insights from a recent extended walk along the way. He also shares some pretty mind expanding realizations, like how choosing fullness over distraction is the path to living each day without regret, or why tuning out quote tight feedback loops allows him to go deeper into life’s riches, experiences, and the surprising way that limiting beliefs imposed by wealth and privilege. Kind of shattered his reality at university, inspiring a Total Life reboot. And Craig also really shares a story that will make you question every excuse you make about why you can’t live with unbridled expression and adventure, and a commitment to honoring who you truly are and sharing that with the world. So excited to share this conversation with you. I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:28] Excited to dive in with you. I mean, there’s so many different aspects of you, your story, how you’ve sort of crafted living in a life that I’m just so curious about. And then of course, diving into things become other things. You grew up in a working class town in Connecticut. A kid who has access to really is drawn from what I understand to computers and music and grow up in this, in this town. And so much of it is woven through in just such like, beautiful and intimate ways. This story about a walk in Japan like decades later. But you made this interesting decision at around 19 years old, to get on a plane to Japan. This is not part of an organized program. You’re not part of, like a pre-planned school. You don’t speak the language. Take me into this.

Craig Mod: [00:03:09] I wanted to drop out of university because when I got to school, the sort of deficit gaps between where I came from and where most of the other kids were at university came from was just really shocking. I’d gotten into a good school, and it was a bunch of kids who were just from extremely privileged backgrounds, and so I didn’t have the emotional intelligence to process it or to respond to it. I think I started speaking with like a fake British accent, like accent. Like I wasn’t even trying to like it was just my brain was just completely haywire. I just remember speaking to someone and they’re like, you have the most beautiful accent. I was like, do I have accent? I was like, Oh God, now I have to pretend to have this accent. There was a lot of things that made it really uncomfortable for me, and I didn’t have any mentors or archetypes to guide me through it or talk to through it, so my plan was simply to just drop out of school. And I thought, well, while I’m still in a school context, I can use that to do something interesting. And I can I can say, hey, I’m a university student in America. Can I come for a year abroad to your university in Japan? Whereas I think if I didn’t have the school credential, that would have been harder to do. It worked out well for that. I just told my school I was taking a year off. I didn’t tell him I was dropping out because my intention wasn’t to return.

Craig Mod: [00:04:25] I felt from an early age being adopted. I think this kind of instills in you. It kind of plants. The seed of you come from elsewhere. And so the pull to discover that elsewhere or the pull to experience elsewhere, was just always so present. And Japan felt like an interesting challenge, like more than Europe, like I felt like Europe I could go to. And if I keep my mouth shut, I kind of look like a European or whatever. So Japan was sort of like going all the way in, you know, in a way to kind of erase who I was entirely, which I think a lot was the reason a lot of people pick Japan historically, but Asia more and more. I mean, I think Shanghai served that purpose a lot in the 2000 when China was sort of in this really interesting moment of ascendancy and not yet such a authoritarian grip on things. But there’s a looseness there. I mean, I used to I was in Shanghai for a few for six months in 2006, 2007, and there was like this really, really wild energy, really interesting energy. And, um, I think the people that choose these places who aren’t from these places are looking for that kind of self erasure and then the ability to rebuild, which is what moving to a culture that will never see you as part of their culture and moving to a culture where they don’t understand your history at all, allows you to do that. So it’s pretty powerful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:46] I mean, it’s really interesting also because I feel like so many of us, when we thought about college, even in the US or in a culture where we understood that we were accepted like nobody asked. That’s a lot of what we were doing, especially the first year or two. Oh yeah, I’m taking myself way back to like trying to remember freshman year. And I was like, I was really excited. I remember like this. There’s a visceral, embodied feeling of whoever I was known as up until this moment. Yeah, I actually get to step into an environment where I can choose whether I want that to follow me, or I can choose to step into it and just show up very differently, and then actively choosing to show up differently. Yeah, but what you did is the extreme version of that. I mean.

Craig Mod: [00:06:26] I mean, I tried with the British accent and at first but I was like, this isn’t enough. I need another language. I need people who don’t understand socioeconomic kind of placements. And but I think it is important to have those moments, especially after high school, after, you know, coming out of your town, wherever you may have grown up. It’s so constricting, you know? And I think that is one of the, if not the most important purpose of college is to get you to reimagine yourself, to rethink yourself, to learn how to think again. You know, these are all the things that I think are critical outside of just ticking off boxes of whether or not I have this marketable skill now. You know, it’s I probably should have gone to a really, really classic hippie liberal arts, tiny university college. That’s where I should have gone. But no one in my family had gone to schools, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:17] Like Reed College or something.

Craig Mod: [00:07:18] Should have gone to Reed. I should have, like, just shadowed Steve Jobs, taking some calligraphy courses. Like, I think that would have made me a lot happier. But it’s daunting, you know, facing that landscape. So you do. You do the best you can.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:31] Yeah. I mean, when you get to Japan, then, you know, one of the things because you didn’t have any language at that point, right?

Craig Mod: [00:07:36] I had actually taken um, two very non intensive years university. So it wasn’t zero, but it was very low like there was 13 or 14 Levels of language class at the university I went to and I was in two. So whatever that, you know that it wasn’t that great. Whereas kids who had studied at like real intensive, language focused universities were who had only done one year were entering at like 11 or 12. So it was pretty wild, like the gap there if you really put in the energy. So, you know, I’d studied a little, but I effectively knew nothing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:13] From what I understand. Also like when you show up, I know a lot of people who actually ended up heading to Japan, sort of like early 20s ish, and they would generally gravitate towards those expat communities and kind of stay fairly insular. Yeah, it sounds like you did almost the opposite. You sort of like immersed yourself and said, and it sounds like for you, maybe the language that was a little bit more connective tissue was music was drumming.

Craig Mod: [00:08:34] Yeah. I tried to not just get stuck in the cliques of foreigners hanging out with foreigners. I mean, all the people in my school actually were incredible. It was super diverse. It was folks from all over Europe, all over Asia, Australia. I mean, it really was like this idealized university experience, and everyone was curious and hard working and smart. So it was a great group. But I was also a musician, and music had been a big part of my identity as a teenager and was also one of those. It was like computers and music were the two things that were kind of like, these are tools I can use to get to a different place. So I immediately joined one of the music clubs at university, which was only Japanese people, and, um, went for it, you know. And that was, that was quite good. And then my life was just immediately filled with, you know, I was in the studio all the time, and I was playing in clubs and, and drinking too much. That’s also where, like, all the drinking started too, because like, Japanese college kids just really I mean, you think American college kids like to drink? Japanese college kids put them to shame. And it was a really great way to feel embedded in, I think Tokyo like getting access to all these secret clubs and like, you know, playing gigs and like, you know, it was great. I was able to invite all the international kids to the, to the shows and, you know, and then we had all our Japanese fans and blah, blah, blah. So it was it was pretty fun. And I had been playing as part of the reinvention thing. I’d been playing pretty much like jazz my whole life. You know, I’ve been studying jazz. I was playing a rock steady and and reggae in high school. And, um, I got to Tokyo and I was like, all right, let’s do punk. So I was I was in a three piece punk band.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:16] As one does.

Craig Mod: [00:10:17] Yeah, yeah, it was fun.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:18] So you’re hanging there and at some point, though, what starts as, oh, let me go to Japan and sort of like there’s this self erasure element, there’s this immersing in a completely new, different context. And then and then really losing yourself into it. How and when does the switch get flipped that makes you say, oh, maybe this isn’t just a moment, but maybe this is actually where I want to be.

Craig Mod: [00:10:42] In some ways, it doesn’t get flipped Ever in. In other ways, I think it flips immediately. You know, I think subconsciously something flipped in the first like week, you know, just like to go from a place where the greater whole doesn’t feel taken care of, where the resources aren’t there, you know. And that was sort of what was the traumatic part of university, was seeing people who came from obviously resource heavy places. It’s just the shock of that. The inequity of opportunity distribution in America really knocked something loose in my like, really shook me. And coming to a country like Japan, I think I could have gone to like Sweden and had probably an identical experience, you know, just coming to a country or even like, you know, the UK in the early 2000 was probably somewhat akin. It’s a little more weird now, but there was something akin to this happening if I was like studying in London. But just that sense that the people, the strangers you pass on the street are taken care of is a powerful thing. My friends weren’t even taken care of. Never mind the strangers back home, you know? And it’s just you just go, wow. Okay, that’s. This is possible. It’s, like, really hopeful. I mean, it’s really, really, really astounding. And part of what I think has kept me here, too. It’s inspiring to be near that.

Craig Mod: [00:11:59] It’s inspiring to live in a place that takes care of the people around you. You know that you feel like there is this thing bigger than us. I mean, what’s the point of building these societies, building these cities if there aren’t going to be if those resources and there is such an abundance of resources is the thing that kills me about when we talk about contemporary stuff. And I mean, really it’s just talking about contemporary America is this inability to recognize the insane, vast, absurd amount of resources that could easily be deployed in such a way that even in the States, it feels like it does here. That would be so easy to activate. And it’s just funny that doesn’t get activated. And it’s one of the things that that I think can be depressing unless you are in places where it is activated, you know. So again, like Scandinavia, big parts of Europe, Japan, and you see it functioning, you see it working not without certain compromises to certain degrees. But I actually don’t think when you talk about, oh, well, there’s this cultural compromise or this compromise, it’s more cultural compromises, more than, oh, that’s because of economic policy per se. You know, Japan does interesting things like you’re a home loan, primary home loan in Japan, the rate as of like six months ago was 0.4%, 0.4%.

Craig Mod: [00:13:17] It means that anyone first home, it’s only for your primary home. If you’re not doing your primary residence, you don’t get that rate. But banks subsidize the I mean, it’s not free, but it’s effectively a free money. You know, 0.4% is like a rounding error. And then you can add things on top of it, like there’s a point 2% upgrade. So if you you pay like 0.6%, you get a life insurance policy connected with the loan, where if you die, it’s totally absolved and that’s the end of the loan. But also if you get diagnosed with literally any cancer, like if you get skin cancer instantly, the loan is nullified. These are really, really, really kind things to do at large. And like the idea of your first home should be or your primary residence shouldn’t be. This thing of stress where you’re worried about crazy variable mortgage rates and you’re paying 6% or 8% or whatever it might be. That’s just one example of how you can kind of create structures that enable people to do the stuff they should do, which is not thinking about mortgages and thinking about paying off loans, but building companies or building businesses or raising great families. You know, these are the things that make that raise the quality of life for everybody, not just the family itself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:28] It’s just such a thoughtful way into creating, stepping into society and creating society in a very different way, like a holistic way where everyone feels like they’re taken care of. I mean, it’s interesting also because you look at, I think it was a couple of weeks ago, the latest version of the Global Happiness Study came out. It’s always the same countries that are sort of like in the top ten. Well, actually not always the US used to be, and now it’s pretty far down the list.

Craig Mod: [00:14:50] Yeah, it was like 29 or something, wasn’t it?

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:52] But it’s the ones that tend to have like really strong social ties and social safety nets, which is kind of interesting to see. All of this I’m imagining like this becomes a part of like what you get really curious about and experience over time. But like when you’re a kid, this is not what’s keeping you in Japan.

Craig Mod: [00:15:07] No, but that sense of safety, I think, I think ambiently subconsciously, you know, set a foundation to be like, oh, maybe this is a place to live. No. What? I didn’t know what I was doing. I was just completely ridiculous. I was blackout drunk half the time. We didn’t know anything about the history. We didn’t. You know, we were studying some of, uh, theology and politics here, but we really didn’t understand anything. And so when spring break hit, my friend and I hitchhiked across the country. We spent a month hitchhiking from Tokyo to Fukuoka and we got picked up by. I don’t know, 20, 25 different cars. And we would get blind blackout drunk with strangers in the middle of the rice paddies in Gifu or whatever. Or like a truck driver’s truck got stuck on a mountain, a snowy mountain near Hiroshima. And we had to, like, kind of get out and help push it up. And, you know, smoking cigarettes. And we’re like, trying to push this truck and we don’t know where we are. So it was it was pretty chaotic. And it was really just like, how do I. I was so hungry for all of it. And it was like, how do we just fill as much of this life as possible with everything we can see and everything we can touch here? And then from Fukuoka, we flew to Okinawa. We took boats down to Taketomi Jima. Ishigakijima met a bunch of interesting people down there, stayed in a crazy hostel. You know, even people I’m still friends with to this day. That was 25 years ago. I still am in contact with one of the people I met on that little trip I saw just two months ago.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:34] That’s amazing.

Craig Mod: [00:16:35] It was pretty. Pretty wild, but that it was really just okay, here’s a safe place to do as much exploring as you want to do. I think maybe that’s really critical. A critical part of it is there was no sense of ever being in danger because Japan is so safe. And, um, I think it just felt like, let’s go for it. Whatever we can imagine, let’s do it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:57] Was there a sense of urgency also? Like was there anything was there a voice inside of you that kind of said, well, this is going to end? Or was it more of just an open ended like, let me just do what I can do while I’m here?

Craig Mod: [00:17:08] Well, it’s just, you know, for a year that first that first year, the plan was kind of to go to California and do some design stuff. And the market collapsed when I was in Japan that first year. So, like, suddenly Silicon Valley doesn’t exist anymore. So I ended up applying to a different university. Um, while I was in Japan, I used the fact that I was in Japan as this kind of like lever to get into a good school, an even better school. So I ended up going back for that. But then in the summer between those two years, I came back to Japan for the summer for three months and did an internship. And then as soon as I graduated, I was back again, in part because the language component was just so compelling. Like that was the hook because I had taken Spanish classes in high school, but I was terrible. It was my worst class by far. I just couldn’t do it without immersion and Japan. I came to Tokyo and I’m immersed in all this music, and I remember we did that hitchhiking trip by day, like 25, after having introduced myself several dozen times. And, you know, you say the same things every day.

Craig Mod: [00:18:11] Hi. I’m going to this school. I like this music. I do this, I, you know, and it’s funny, it was like the wax on, wax off thing with The Karate Kid. You know, he’s like, why is Mr. Miyagi having me do all this stuff? Why am I painting the fence like this? And then suddenly it was just there. It was like, oh, I have language now. That’s wow, this is really exciting. And I think the music component in having a musical ear is a big help for that as well. And then just the kids I was surrounded by were great, great people, and they were all talented. And so they were all just a couple levels higher than me. So I was always hearing a slightly different grammatical deployment, and I was like, oh, that’s interesting. What’s that, what’s that, what’s that? That was just addictive to feel your body absorb this new language. And with it, like we were talking about earlier, the the ability to be someone else, to feel your mind move in different ways from your mother tongue. All of that was just so seductive. So I came back to go to university again and keep up the studies.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:06] And at the same time, it’s interesting because you you actually have a chapter in, in the latest book, Things Become Other Things, literally titled language where you describe like, don’t just hang out in Tokyo, go out onto the other places, but also to hear the quote, dirty language and then also then you. It really gets memory where you kind of drop into like how what you hear in like the outer areas just brings you back to your childhood, the way that you and your friends used to hang out. So there’s like a familiarity at the same time?

Craig Mod: [00:19:36] Yeah. Because I mean, all languages, like, if you’re an alien looking down all languages identical, like. Right. There’s no real difference between. No huge differences between the languages in the end. But for us, like on this kind of like up close scale, there certainly are. And so then when you start looking for analogues, you know, and when you get out into the countryside of Japan, at first, unless you’ve really learned the language, you kind of don’t hear what the local dialects are doing. That’s also part of what’s really fun about the travels is and the walking and the meeting. People in the middle of nowhere is luxuriating in these different dialects, and you begin to realize more and more it’s like, oh, okay. In Tokyo, you don’t really meet people. I didn’t meet that many people. That reminded me of where I came from. But walking on the Key Peninsula in my near was talking to like, old fisher people or boat workers or the AMA divers or whatever. It’s like their language. And where I came from, it was just like, wow, okay, there’s something, there’s something. It is in conversation with one another, even though they are literally a world apart. And that’s fun. I mean, like having the ability to do that. I think to notice that and to play with that is also exciting, because it means your language has hit a certain level as well. And, um, skill acquisition is fun, it turns out.

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:56] Yeah. Who knew? Right? Yeah. So as you decide that. Okay, I’m going to make this my home for, like, however long. Um, that feels right. You start to build a life, you start to build a living. You, as I’ve heard you describe for the better part of 13 years, live in a room that is a six tatami mat room, which is like, think of it like kind of like the size of a yoga mat, almost. And six of those. And the Western mind hears that, and they’re like, what? Yeah, but it’s not that uncommon, especially like in the life that you were talking about in the time of your life.

Craig Mod: [00:21:26] Well, yeah. Not only is it not that uncommon, but also like in New York, people live in really tiny places. In San Francisco, people live in really tiny, expensive places.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:35] Especially now, like postage stamp sized places. Yeah.

Craig Mod: [00:21:38] Yeah, it’s I think it’s even it’s worse and worse now, but Japan, I mean, I think Americans have a very perverted sense of, like, expected space. You know, it’s just like there’s America is big. There’s a lot of land, whatever. Building isn’t that expensive because of whatever reasons. So I think a lot of Americans are freaked out by this idea of minimalist. But Europe, you know, it’s like, look at apartments in Paris or in London or New York. I mean, there’s a lot of smallness out there. Italy, apartments in Venice, things like that. And Japan, I mean, Tokyo. One of the great gifts of the city to people is that you can live in pretty much any neighborhood you want, and there’s affordable housing in every single neighborhood. And if you’re okay with something that’s a little older, it’s easy. It’s easy to do. And you know, the cost is just so low. I didn’t come from an abundance, you know? It’s like my bedroom growing up was actually smaller. I think it must have. I’m just. I’m trying to. I’m trying to remember the size of that bedroom. It was. It was so small. I mean, it must have been 100ft². I want to say maximum. Is that even, like, what would that be? Ten foot by ten foot is 100ft².

Craig Mod: [00:22:46] So yeah, if that it was like that’s basically the size of the bedroom I grew up in. So like, you know, I came from I came from a very sensitive sense of, uh, of growing up. And so to, to live in these tiny rooms in Tokyo, which also were normalized. And so all my friends were living in small rooms. It wasn’t like everyone was in a big room and I was in a small room. It was like a superpower, you know, it was really incredible. And then it also meant that I could be uncompromising because rent was low and I could focus on the work I wanted to work on. I didn’t have to take jobs to pay for rent. I didn’t want to pay jobs I didn’t want to do. And I could just focus on thinking about books, thinking about book making, building relationships with printers, building relationships with writers, artists, you know, just trying to engage with that world, trying to basically give myself kind of a post-grad grad program of my own about how to be an artist and how to be a creator and how to be a writer, and that and do it all in one of the biggest cities in the world.

Craig Mod: [00:23:43] So that’s kind of what that afforded me. But yeah, it’s a good training program. I feel like everyone for a couple of years in their 20s, should live in a six mat to Tommy Rome apartment and sleep on the floor on a futon because you realize, like, not only is it not that bad, it’s actually quite comfortable and as a material. So Tommy is is pretty astounding. I mean, I’ve since then, I’ve never lived somewhere without tatami. I always bring I always have to Tommy made. So that’s the other thing that’s interesting about tatami is like, it’s standard sized, Tokyo has one size and the Kansai has another size. But tatami makers will come to your house and they’ll make perfect fit like a glove to Tommy for any room, any space, any corner. And they’re happy to do it. And it’s not that expensive. So it’s actually this kind of incredible material to create these spaces of, you know, just kind of supine leisure, you know, where you can just kind of lie on pillows and read books and, you know, take naps and roll around with your dog or whatever. It’s like, it’s an amazing building material. It’s an amazing flooring material.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:47] Yeah. I mean, it sounds super cool. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. I don’t want to skip over what you mentioned, though, because I think this is so powerful, this notion of you having the ability to live in a comfortable space and really control your means gave you the space to be uncompromising in what you said yes to. So you start to develop an interest in books and book making and design and art. And rather than saying, okay, so I’ve just signed a lease for a whole bunch of space, and I literally need to take a job largely to cover my living expenses. You make the opposite decision that a lot of people make and say like, let me minimize this. Let me sort of like really strip it down. Because the thing that matters most to me is I want to do the work that I want to do, and I want to develop the aesthetic sensibility that I want to develop, and that’s paramount.

Craig Mod: [00:25:36] Yeah, I mean, for me, it wasn’t even a question. It wasn’t like, oh God, should I move into a bigger place that I like? I had very little savings, and at that point I did have marketable skills because I had kind of spent my teenage years again seeing technology as the way out, as kind of the hack to get somewhere else in the world. So I’d done an internship when I was 19 at like kind of a big, quite boring, but still everyone was really sweet, very nice and sweet to me. Company in the Valley. And it paid really, really well. And I just remember feeling that summer I was walking around San Francisco with a friend and saying to him, Rob, I was like, Rob, I you know, I can’t do this. I’d already, in my teenage years, essentially concocted some artistic impulse that I felt I had to follow, that I felt I had to kind of, like, abide by or respect or at least see through to some degree. And so when I got to Tokyo, too, it was just I was able to kind of continue that. And because I had touched that world of kind of high paying office job stuff early on, I was really lucky. I mean, that was like just such a fluke of an internship that I got random connections, IRC stuff I was doing when I was 13 really, really, really, truly, just like sliding doors randomness. But because I had already had that experience, I’d sort of quelled that question mark inside me where I was like, well, what if I went and did this? What would it be? And that was kind of an ideal environment. Everyone was really sweet. There was no stress, kind of working on interesting problems, and it paid really, really well.

Craig Mod: [00:27:10] But the commute made me want to shoot myself in the face every morning. And I was just like, I remember making a covenant with myself in my Honda Civic, you know, with the muffler about to fall off. I’m on 101 commuting, and I was just like, we are never, ever, ever gonna ever agree to anything that forces us to do this again. I mean, it just felt death happening, you know, 19 years old already. So that kind of let’s minimize costs in order to maximize artistic exploration and artistic freedom. It was an easy decision for me to make. That said, I think that you do need stresses on the system in order to push it forward. And I do think there like, look, I’ve just been really lucky. But I also know that Tokyo can be so easy that you can tread water forever. And I know people, you know, you meet people who are in their 50s and 60s and 70s or whatever that have just been here forever, and you can just see how they’ve sort of treaded water in a way where if they had maybe been doing the same thing they were trying to do? Like in New York City? There’s kind of a pressure because there’s so many people doing competing, and I think that could be really healthy. And so it’s just a matter of finding how do you balance that? But getting the basics of like not paying $3,000 for a shoe box is pretty silly. Get rid of that. Like you don’t need that in your life. And you can kind of figure out other ways to inject self concocted or found external pressures to push you forward as an artist. But the cost of living thing is a big cornerstone of it all.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:46] Yeah, I mean, it makes a lot of sense, and it really allowed you to just lean into this other part of you that was just like more and more and more like, this is there was something speaking to you, like the aesthetics of bookmaking and art and design and also writing. You know, I know that you had sort of like a stint back in the Valley for a hot minute when the iPad comes out, then Flipboard, and it becomes sort of like the darling, you know, of the new apps for that, and you’re there for a little bit, and then and then you leave that to do a writing residency. Yeah. What’s the through line with writing for you? Is it something that was always there, or is it something that kind of emerged later?

Craig Mod: [00:29:21] Oh, it was always there I was writing. I remember I was writing Akira two like fanfiction when I was like ten or whatever.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:28] Oh no kidding.

Craig Mod: [00:29:29] Yeah, I was yeah, always there, always there. I always loved it. And yeah. And was always just compelled and drawn. I remember Stephen King, The Dark Tower, The Gunslinger, that first book. I think it was like one of the first adult books I ever read. Maybe it was like fourth grade. It’s like when you experience a great piece of art, a great movie, and you feel kind of filled with the essence of that thing and you want to emulate it. I mean, I felt that wholly with my entire body. I remember it so distinctly. I remember like the opening of, um, book two, where he’s like on an airplane and trying to eat this tuna fish sandwich. And, uh, and I like that’s seared into my mind. So, yeah, this connection, this, this love of or connection to books and like, this sort of almost like Pheromonal Modal interest in prose. And I was reading Stephen King because that’s all anyone read around us. That was the that was the deepest, most literary thing that was in, in, in town. And then as I got, I got into, you know, university and actually one of the greatest there were a couple of great things in the tumultuous first years of university, and one was freshman Writing seminar. And we read the House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. And, you know, hilariously, she’s writing about this kind of immigrant experience. And that book spoke to me, like, so, so intensely. Like, I’m definitely not who that book is supposed to speak to, as far as I can tell.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:52] Right?

Craig Mod: [00:30:52] But it was it reconfigured my brain completely in terms of like, what prose could do and what how prose should feel. And I just remember, you know, emulating her soon after. And actually, I was in this emulation mode and I was writing short stories, and I wrote a short story, strangely enough, about Brian. So, you know, this is the main character, basically the are the ambient main character and things become other things. And the first piece of writing I ever really put out in the world was this Brian short story, and actually won an award and was included in this national collection of fiction freshman Writing seminars all over the country. And Macmillan, I think, picked, you know, there was like 30 short stories from all over the country. And so that that got in there, and I was actually commuting on 101 on the way to that job. Actually, I was going on the way home from that job, and I got the call. They said, hey, you know, we’ve picked you for this thing. And I had written some insane pseudonym in For my name. Like, like I forget what it was. It was like, I think because I was really into like Doctor Octagon the rapper or something back then.

Craig Mod: [00:31:58] And they were like, you should use your real name, like, don’t use Doctor Octagon. And I was like, okay, fine, yeah, use my real name. But it was um, that has always been there, like this kind of ventriloquistic impulse, you know, and really like the house on Mango Street. Thing really shocked me. I think because of the simplicity and the power going hand in hand in a book like that I’d never seen before. There were no airs, there was no pomp, there was no pretension. It was just really straightforward, simple prose that just freaking cut right to the heart. And I was like, wow, okay, this is the kind of literature that represents where I come from in a way that none of this other stuff does. You know, like Ulysses, like, that has nothing to do with me or Pride and Prejudice. That has nothing to do with, you know, there’s there’s no I’m not seen in any of that literature, but there’s something about that prose that really made me feel like, wow, okay. Yeah. Sit in this register for a while.

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:57] Yeah. I mean, when things come together like that, it’s just. It’s so powerful. Often I feel like we don’t have moments like that often in our lives. But when we do, I think a lot of us, when they drop, they can often be so jarring that rather than saying yes and standing in a place of wonder and curiosity, we kind of reject them. We rebuff them. We even tell ourselves that this isn’t happening. I’m not seeing or feeling what I’m thinking. I’m seeing and feeling because to acknowledge this would be so jarring to my system right now that it would be disorienting on a level that I don’t want to be disoriented. So we kind of push it aside and then wonder why, you know, we haven’t found our thing or our things or our whole lives when it’s been knocking at the door of our psyche for decades.

Craig Mod: [00:33:41] Yeah. It’s funny. I mean, I think I felt the exact opposite. I mean, maybe this is self-selecting. It’s like, as soon as I feel any of those, I’m just, like, running towards it as fast as I can. Kind of, like, without looking, without even looking, you know, ten feet down the road. I’m just, like, barreling, barreling in that direction, which I think the hitchhiking across Japan trip was sort of like that. We were just like, so hungry. We wanted to just be fully intoxicated by how do we maximize, like just being here and touching everything and smelling and feeling and eating everything. And I think that trip was was emblematic of that. But yeah, I think a lot of most people are really great at creating excuses not to do things. And that’s why the cost of living stuff, I think, is great to have removed, because that tends to be the most expensive excuse. I can’t do it because I got this thing, I got to do this thing, blah blah blah, blah blah. Especially when you’re young, when you’re older, things change, and especially if you’ve gotten if you opt into a certain set of things in your 20s and then you arrive in your 30s and you kind of double down on that stuff, like by the time you’re 40, you’re not going to it’s almost impossible to change. Like if you have got a certain kind of mortgage and you’ve got a certain kind of friend group, and you have kids and you have this thing and you have all these financial responsibilities.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:55] Yeah, it’s just a lot harder. And it’s not just your decision anymore at that point also.

Craig Mod: [00:34:59] Yeah, exactly, exactly. So it’s really about baking in those impulses as soon as possible, really in your teenage years. And it’d be interesting to, to do some research on, like how do you cultivate that in a teenager to get rid of that fear?

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:12] That would be amazing actually. Yeah. It’s interesting because you referenced also, again, sort of like the, uh, the cross-country hitchhiking and also you’re running towards this impulse in, in your case, which I think brings us to also my curiosity around, you know, the big walks. So at some point years into your trajectory, you basically, you know, a guy named John McBride and Ozzy and people may or may not know his name kind of says to you, hey, let’s go for a walk. Yeah. Yeah, but not just a short walk. You know, like, it’s not like, hey, let’s meet for a walk and have a little coffee and chat. And this starts like a season of these giant walks. Kind of take me into this a little bit.

Craig Mod: [00:35:50] Yeah. John invited me. I mean, John and I met through a mutual friend, and John was involved with the art world. John has this, like, really Forrest Gump, Ian history. Like he ran Sky TV. He launched Sky TV with Rupert Murdoch here in Japan. He was setting up airline routes for Ansett, which was an Australian airline that doesn’t exist anymore. But I think he opened like the Osaka Sydney route or something like that. So he just has this. He had this really bizarre history, and then he basically retired when he was like 45, let’s say, because running Sky TV was so intense. And then he shifted into because he is at in his heart, like an academic. He shifted into the art world. And so he had been deeply engaged with Aboriginal art. I don’t know if you remember, about 20 years ago there was kind of this world tour at all, the major kind of modern art museums of contemporary Aboriginal art that was happening, these huge pieces by these kind of really old folks in the in the desert and stuff. And like, John was kind of instrumental in doing that. And he supported all of these young artists, essentially buying lots of their work, collecting it and then doing donations. So he has like he has, you know, collections at the British Museum and other museums around the world in order to give a platform to these younger artists.

Craig Mod: [00:37:09] That’s kind of that was the purpose of his collecting and donating. And he learned this all from his mentor, who was a big gallery director in, in, um, in Australia. So because he was doing all this art stuff. Um, I had done an art book and a friend was like, oh, you guys should meet. And we met and it was just like, we met for breakfast. And we stood up at 5 p.m., you know, it was just like, we just like, instant, like, you know, like mind meld. And, um, it was fun. And then he just kind of, you know, he’d invite me on little things. We went to James Charles House of light with a couple of Australian artists who were visiting, and that was kind of interesting. And then I don’t remember exactly why, but he had spent his late teens. He came to Japan when he was really young. He spent his late teens in Japan doing research, Japanese literary research on the road. So basically going walking the Tokaido, walking the Nakasendo, walking the 88 temples, walking the Oku no Hosomichi market in order to kind of understand the literature.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:06] For those who also don’t know any of those references, these are long like walks, you know, potentially hundreds of miles or kilometers.

Craig Mod: [00:38:12] Yeah. So like there could be 1000km or. Yeah, you know, 400 miles, 500 miles, things like that. So he had been doing that in his late teens or early 20s, and he kind of took a break from that. And then in his early 50s, late 40s, early 50s, he kind of came back to it. And just as he was coming, coming back to it, we met and he was like, oh, hey, you should come, like, come to Koyasan with me. You know, I was like, what’s that? It’s funny. It’s just so easy to not because history and culture can be really inaccessible, especially if you come from a place where there is no culture, there is no history. So you’re not thinking about those things. And if you don’t have someone to kind of go, hey, look, there’s a door here. Actually, you know, you’ve been standing next to this door for 20 years or at that point, like 13 years. Why don’t you open this door? Has this been here since the day you arrived in Japan? It’s like what? Oh, yeah. I guess there is a door here. Let me open it. Oh, wow. There’s historical walks and they bring you to incredible places and, you know, places like Koyasan that are just filled with this kind of power, spot energy and incredible nature and history. And then the more you dig the language and just kind of quirkiness of of culture, you know, like the the monks up on Koyasan, which is like the, the center of Shingon Buddhism, you know, they’re very bizarre people.

Craig Mod: [00:39:32] You know, there’s like one who’s a famous race car driver, you know, it’s just like, well, who what what is happening here? So he just kind of unlocked or just very gently opened the door that was always there that I could have always walked through at any moment. Like when I, instead of hitchhiking across from Tokyo to Fukuoka, if we had known there was a historical walk from Tokyo to Kyoto, oh, 100,000,000,000%, we would have done that. But like, we just didn’t know that there was no one talking about these things. There was no one exposing us to these things. So, like, what’s the poor man’s version of doing a historical walk. You hitchhike because that’s all you know. So I think the physical challenge of the walk would have, like, totally lit our 20 year old minds on fire. But like, yeah, we’re going to go do that. So he just kind of opened that door for me and started inviting me. And he had a kind of freedom because he, you know, he had done his work. He had compressed 60 years of work into 20 years, from 24 to 44. And I had come back from my stint in California, and I was back living in a shoebox.

Craig Mod: [00:40:34] You know, my cost of living again, I’m 33. My cost of living is $1,000 a month. So I had this freedom to, like, say yes to whatever he was going to do research. And we started researching together. We started walking together, and it just kept going in a way that felt intuitive and and also just like an easy friendship. That’s really what it boiled down to. You know, it’s just funny because, like, people meet us and they’re like, they’re like, oh, are you father and son? That’s awesome. You know, he’s 20 years older than me. And of course, that just pisses John off. You know, he’s just, like, totally annoyed by that. And then and then we’re like, no, actually, we’re not father or son. And then they’re like, oh, they’re like, oh, I see you got the young lover, which we also just find hilarious because you couldn’t have less sexual energy between two human beings, like two living creatures. Honestly, just an utterly effortless friendship. And I don’t think there’s anyone in the world that is easier for me to travel with than John, you know? And so if we’re together for two weeks, 24 hours a day, sleeping in the same room, essentially, you know, it’s like you get all these tatami rooms, you’re just sleeping in a row.

Craig Mod: [00:41:44] It takes zero energy for me. And in fact, it’s it feels mutually kind of like elevating and energy giving. I think that was also why we continued for so long, is because that doing these walks together, just because it was so, it really was, for me at least, maybe for John. It was terrible and he was just totally losing his mind. He’s like, oh my God, Craig, he’s complaining about this thing again. Or he’s, oh, you know, he’s doing this, or he wants to walk too fast or, you know, who knows? But for me it was just pure joy, effortless, pure joy of this world, these doors being opened. And the more doors and more doors and more doors and watching John move through the world as an archetype, the way he uses language, his kindness, his patience, his ability to manipulate people in the best possible way. So like to get into a shrine that you’re not not normally allowed to get into. Like watching him use language to finagle that or, um, just getting access to things that would otherwise be off limits or blowing people’s minds to such a degree that they say, hey, I have this thing. I’ve never shown anyone. Let me show you guys. And watching that all kind of unfold completely reconfigured my brain in the best possible way.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:51] I mean, there’s something so beautiful also about this notion that. So you’re deepening into this literally, like chosen family level friendship, and you’re exploring the world together, you know, and you’re deepening it. And you also like. And there’s a there’s a physicalization of it. Yeah. You know, like, you’re literally moving through space the entire time that you’re doing this. And it’s we rarely do things like that. Maybe we do it for a hot minute. Like I said, you know, I’m very fortunate. I live in Boulder, Colorado. Like, nobody goes for coffee. Here we go for hikes, you know? So I’m out with friends all the time for a couple of hours in the mountains, just walking next to them shoulder to shoulder, and developed astonishing friendships in a relatively short amount of time just by doing that. And I can imagine, like, what if you extended that to a week? What if you extend it to a month? What if you extend it to two months, like 30, 40, 50, 60 days? You know, the full sweep of, I’m sure, emotions physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual comfort and discomfort have to emerge and boredom. I have to imagine that’s a part of the experience also.

Craig Mod: [00:43:53] Well, boredom is when you’re alone. When I’m with John, there’s no boredom. It’s just. Yeah, well, it could be with John. The the one thing that can. It’s not necessarily boredom. It’s just information overload. I mean, John is certifiably, I would say genius level. You know, this is why he’s running a company for Rupert Murdoch in the 90s. This is why, you know, he’s setting these things up in his 20s as kind of a savant. But because of that, his notion of enough information is like 400 billion times more than a normal person.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:25] So completely different set point than the average mortal.

Craig Mod: [00:44:28] The thing with John is like, sometimes I just have to walk away. He’ll be he’ll talk with someone for literally an hour and a half more than I would talk with them. You know, it’s like it’d be five minutes would be enough for John. He’s talking for two hours. He’s taking notes on all this. I’m just like, this is. It’s just overload. So that’s the only point of boredom is when things like that happen. But it’s, you know, it’s all coming from such a good place. And I think it’s important to also note that hilariously, like my editor at random House wrote me a note about something about one of the chapters. Like a John chapter. And she’s like, oh, it’s so amazing, this fatherly figure. Da da da da. And I forwarded it to John, and he was like, just mortified because he’s like, we there’s no fatherly. There’s no hierarchy present at all in the friendship. It is just it’s just a friendship. That’s it. And there’s something really nice about that. And yet from the outside, everyone is constantly trying to like, you want to map it 100%.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:25] So when you start going out on your own, then. And when I use the word boredom, by the way, I wasn’t using it as a negative, you know, because I would imagine when you start going out on your own and okay, so now you’re taking these long walks on yourself and you meet tons of like, interesting characters and people and the places themselves become characters. And this as you’re walking. But I wonder also what the role of I’m literally out on the road, you know, and there are going to be long swaths of time where all I can do is look like, listen, smell and be with my mind. Yeah. Yeah. And how much of that is also a part of the experience of these long walks for you?

Craig Mod: [00:45:58] Yeah. I mean, that’s ultimately the entire experience. That’s the point is to get to those places, to cultivate that that kind of space of boredom in order to heighten attention, in order to heighten all the other senses. Because when you take away that stimulus of the phone, the internet, infinite amounts of information coming into your brain all the time.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:20] And we should mention, by the way, when you do these generally like technology stays off for most of this.

Craig Mod: [00:46:25] For most of it. Yeah, it’s I kind of have these rules. So yeah, I’d been doing all these things with John, and then I started tiptoeing my way out and doing things alone just because there was more stuff I wanted to do. And John would be, like, busy or he wouldn’t be in the country or something. So I started doing these things on my own and building up more and more confidence of being able to do them on my own. And, um, once I started doing it on my own, I very quickly realized I wanted to I needed a set of rules. And I’d actually done Vipassana, a ten day Vipassana retreat. At the same time, I started doing a lot of these solo walks, and Vipassana retreat was a ten day. No, obviously no technology thing. And I think what was shocking about that was feeling the my physiological addiction to information constantly entering my brain. I just wanted that so badly. And doing Vipassana showed me how to move beyond that and actually how present that really was. And so I kind of came out of that way more sensitive to how my phone was making me feel, or how certain websites like Twitter made me feel. And I tried to cut as much of that back as possible.

Craig Mod: [00:47:26] And so on the big walks I had my rules of like, no social media, no news, no podcasts, no no anything that allows you to teleport, essentially, and you have to be fully present in the walk in that moment, in the walk. When you do that, you really do open up these spaces in the mind. So when you when you get rid of that inundation of information, which I think we’re all suffering from for the most part, like everyone listening to this right now is probably jogging and doing something else. And like, you know, it’s, ah, they’re cooking while they’re listening to this. There’s like, you know, multiple levels of multitasking constantly going on. And I think what’s great about walking is a physical act is it’s really hard to do other things while you’re doing it. It’s like you can walk and chew gum, but, you know, walking and looking at your phone is really stupid. And it’s like both things are kind of suffering. And so while walking and getting rid of all that information, you just feel your mind open up. You feel these, those parts of your mind that were otherwise filled with essentially meaningless information. It’s so much of the news that we consume. Wait a week and get the summary of it, because it’s going to change anyway, especially now with the chaos of of these news cycles.

Craig Mod: [00:48:32] So the idea that everything has to be consumed in real time is sort of a contemporary pathology that we’d probably be better without. And when you start to get rid of those, those sort of inroads into your mind. Yeah, that boredom thing kicks in. But what that boredom thing, that space of boredom allows for is just, at least for me, an incredible amount of writing. So I just find my mind immediately wants to write. It fills all of that stimulated space with words, sentences, paragraphs, thoughts, and desires to connect with people and desires to synthesize what they’re saying. And it heightens my awareness for quirky things that they might say, strange things they might say that are unique to that person or of that moment. And I’m just way more receptive. It’s like the antennas are just so much stronger for all of those things. And then also, just like patterns in the world and looking for like in Japan, all over the country, there are these hidden Christian signs that are sort of present all over the it’s very weird, these strange little black and yellow signs about Jesus’s blood. I mean, it’s like very much like you’d see driving around North Carolina.

Craig Mod: [00:49:39] And it’s like, why are these signs in Japanese all over the country, you know, on like little barns and stuff. And so it’s noticing that and which. Otherwise you just pass by and you kind of never take a second look at it. Or like the Kissaten. It’s like when I first walked the Nakasendo, which was from Tokyo to Kyoto, I didn’t intend to eat pizza toast every day. I didn’t intend to go to Kissaten, which are these mid-century Japanese style kind of diner cafes. But I’m walking. I don’t have any stimulation, and I’m hungry. And I start noticing that everything is shuttered except for barbershops. And like kissaten, it’s like, okay, this is another pattern to investigate. So it just it gives your mind the space to engage fully with the world in a way that being plugged in doesn’t. And the walk acts as kind of a forcing function for it all because it gives you purpose. I like walking, but for me, and I’m lucky in the sense that my body likes walking too. Like I can do 3040 k a day. I can carry a big pack. I was always really, like, self-conscious about my my like very muscular, but, you know, as like because, like, pants like never fit me. Because my.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:49] But now I finally understand why it’s there.

Craig Mod: [00:50:52] Yes. It’s like finally this, but has a purpose. It’s like I could climb, you know, seven mountains a day with a 30 pack. And, you know, it’s like whatever. Like my butt’s like, yeah, give me more of this. So it’s it was just funny. So, like, I’m lucky in that sense that, you know, I can walk for 40 days. And my body, for the most part, is okay, but the walking itself is not the thing that I’m ensorcelled by. I’m not. I’m not seduced by walking. Walking as a physiological act opens up in the mind and makes it easy to say, I’m going to get rid of these other things, because it that point to point purpose lays a foundation of purpose for your day. I’m going to I have to get to this place, okay? I’m going to get to that place. That’s the work for today. And it makes it so much easier for me at least, to say, okay, no social media, no news, no teleporting. And so that’s really the power of the walk. And that’s what I really love about the walk and also biking. It’s just too technical. It’s like you have to think about gear and maintenance and okay, you got a flat and you got to deal with that with walking. It’s just like there’s a purity to it and a simplicity. Just your feet. That’s the only thing you really have to care about. Like, worry about your feet. Make sure they’re okay. Make sure your knees are okay. That’s about it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:03] I mean, I love that, and it sounds like for you, like there’s an attunement that happens when you’re walking. It’s like especially like, without the technology out there, you’re like, you’re paying attention to the environment, to everything around you in a way that you wouldn’t be if you were cycling or if you had tech or if you were hitchhiking or whatever it may be. And then, like when you get to a place, at the end of the day, I know you’ve written about sort of like oftentimes the cycle that you have when you’re on these longer walks where you’re out in the walk and then in the evening you might sit down and then like basically collect your images and your thoughts and maybe write for 4 or 5 hours that evening, you know, like and do this day in, day out. I remember I think it was it was probably pizza toast, that book, if I have it right and tell me if I, if I don’t, we’re basically you were sharing in real time with a select group of people, but and they could write back to you, but it didn’t get passed on to you until you finally returned. And then you basically got everything all at once. Was that the book or was it kiss by kiss?

Craig Mod: [00:52:55] Yeah, the Kiss by Kiss is the book that came out of that walk. But as I was doing that first big walk, that was kind of member. So I have a membership program and it was sort of the first member funded walk. I kind of designed some permission from the members to do it. I built this really weird SMS messaging system where I could message a little note in a photo every night, and then people could respond, but I didn’t see the responses and they were collected on a server. And then ideally we were going to have it auto kind of lay out this book, but that was too complicated. So I just gave the Excel file of responses to a designer and said, hey, can you lay out this book? Here’s the templates, don’t show me the messages. And and then he laid out the book, hit print on blurb, got one book it was waiting for me at home at the end of the walk. So just to again, like thinking about the tightness of contemporary communication, like of these loops, these communication loops, like until 40 years ago with before email, it was like you had you wrote a letter. That was it. I mean, it’s so crazy how how recent that was where that, you know, or you made a phone call.

Craig Mod: [00:54:02] But if you really wanted to like, sit with your thoughts and like send someone something considered, it was like you wrote a letter that took a couple days, and then they took a couple days and they came back. So that loop was like maybe a week long of communication. And now all of our loops are on the the millisecond level. It’s like people are watching in real time. There’s read receipts, which I think are one of the worst things that we’ve ever self-inflicted harm that we’ve ever done to ourselves is like putting read receipts on messages, uh, talk about like, traumatizing teenagers. Like, that is absolutely the worst thing we could have done in messaging apps. And so all these loops are just so stupid and tiny and knee jerk and reactive. And the expectations are that the responses are going to be immediate. And so when you can kind of subvert that, you just find people open up in a way that they don’t say, like normal email or normal social media. And so I got this book at the end of The Big Walk, and it was just really mind blowing, like kind of the stuff people were writing to me, just the intimacy of it, because they knew I wasn’t going to see it immediately.

Craig Mod: [00:55:00] So I think that gave him a little bit of a permission to kind of dig, dig emotionally more deeply. And then I went back and responded to those in essays over the course of like several months. So we were able to take what I was able to mix, sharing how I felt in real time with kind of this older analog level of communication loop in terms of time frames, and then fold that back into doing newsletters that were then doing email essay responses to some of the questions that were posed in the book. So it ended up being this really kind of beautiful experiment that was, for me, extremely successful, hammered home important it was to protect yourself from those loops, from the quickness of social media to to enable your mind to really luxuriate and sit in the boredom spaces and what your attention is drawn to in those moments of boredom. Because when the loops are tight, you’re constantly getting pinged and there’s always another dopamine ping hit waiting for you. And so say I was doing real time communication on the walks. A piece of my mind always thinking about, oh, has someone responded what I should look? Maybe I should respond.

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:08] Yeah. And like, how much would you miss? I mean, by not being there.

Craig Mod: [00:56:11] Yeah. You’d miss everything, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:13] It’s like when I go to a concert, right? And I see everybody holding their cell phones up over their head. And I wanted to sort of, like, capture the moment and get credit for it. And just, like, constantly. I’m just like, what if you were just here? Yeah. Like, you’re never going to see that again and you’re just sending it out for social currency so other people know that you were there, but like, you’ve just missed something that could have been just gorgeous. Yeah. You know, and we do that all day, every day in our lives now in everyday events and everyday interactions, like with a barista or in like the great moments. It’s just like we’re partially there but rarely ever fully there. And I’m always wondering how much of our lives are we missing through this simple quirk of technology and behavior?

Craig Mod: [00:56:51] All of it. We’re missing all of it. We really are. I mean, I get traumatized by people on Instagram who do like 20 to 50 stories a day. I still use Instagram because when I’m doing these big walks and people want to connect. It’s actually a great way to connect with businesses out in the middle of nowhere, or young people out in the middle of nowhere, and it kind of creates these threads back to those places that have paid really meaningful dividends over the years, just of staying connected or being able to call on for favors or something if I’m going back to the area. So for me, Instagram has that kind of value. So I open it every now and then to just take a peek. And I’m just shocked at these people who every day are doing 20, 30, 40 stories and hour. You just realize are so manipulated by the system itself. And some of these people are quote unquote artists or creators. And I want to kind of just shake them and go, okay, take a month off. You’re not allowed to post any stories. You’re only allowed to do your work. Just work on your work. Get the writing done. Go take photos without thinking about Instagram. It’s like sit in that space because I think it’s easy to forget what life outside of that dopamine loop feels like. And I do think the art suffers. I think it is impossible to make great art, which is art that is getting to certain kinds of truths, or art that you know is offering a new perspective on things when you’re plugged into those systems. Because those systems.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:20] Are so.

Craig Mod: [00:58:21] They’re so anodyne. That’s the thing that is so frustrating about it. It’s like no one has ever made great art in an Instagram story, ever. There’s no one’s ever like, you know, no one’s seen an Instagram story and been like, this belongs in the MoMA. That will never happen because the system doesn’t want that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:40] Although somebody may have taken a picture of something that’s great art that’s hanging in the chair with Instagram, but I so agree with that. In fairness, though, I mean, I think a lot of people, especially like people with an artistic impulse, people who are makers and artists and like they really want actually, they want to make great art. They want to figure out what is my truth in this moment in time and figure out how can I express it in a way that feels aligned with me. And and at the same time, they bought into a mythology that says, you have got to spend a substantial chunk of your time out there actually being sort of perpetually public, because that’s how you’re going to get the work out. But we never look at the opportunity cost of that. Right. And then we’re always wondering, why do I always have to keep being here and here and here and here over and over and over and over and never asking the question is part of this because I’m taking a pretty substantial chunk of my bandwidth, my instinct, my attunement, my attention, my creative expression, and allocating it towards that rather than allocating it to the craft so that I can create something so that when I do step into those platforms and those communities and those spaces, what I have to offer is now at that level that you’re describing where instead of people saying, oh, they’re just like, oh, sweet, what? Oh, wow, I’m in tears. I need to actually tell everyone and bring everyone that I know here, and we want to participate in this. I think so often we don’t think of the opportunity cost to the work itself. When we’re doing this.

Craig Mod: [01:00:09] There’s a huge opportunity cost. Community is so important to creative practice. It’s so critical. And I think the the real move for young artists is to find ways to create community in physical space and create recurring community events, connections, Actions meetups that can be completely divorced from social media stuff. And I think very quickly you realize the richness of that is 100 billion times greater than whatever phony kinds of connections you feel like you can make on Instagram Stories. It’s like Instagram stories aren’t worthless. Tiktok isn’t worthless. But you have to, I think, be very careful of how you engage with that space, because that space wants you to just live there forever. That space is not. It’s not your friend.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:57] What am I saying no to by saying yes to this? I think we don’t ask that question enough, and we’ll be right back. After a word from our sponsors, I want to dive into that notion of community a little bit more. You mentioned earlier, um, a membership, people that are literally I mean, you built this fascinating model. I’m absolutely I’m so fascinated by this. We’re effectively you have a community, although I’m actually curious whether you actually call them a community. You have a group of people who’ve raised their hands to say, like, what you’re doing is interesting to me. It’s cool to me. For some reason. I want to not only ride along with you and participate in the things that you’re sharing and what you’re experiencing, both in terms of whether it’s a newsletter or, you know, every couple of years, you know, beautiful social objects that really distill it into things. They’re not just saying, I want to participate in it. I want to live vicariously a little bit, but I also want to pay you so that you can go and do these things and then create these things. Take me into this model because it’s also not different, because you’ve also, you know, you’ve incredibly generously written something like 40,000 words, basically over a six year window of having this paid model explaining, like, this is what I did, this is what I learned. This is how I’ve changed it. This is the evolution of it. And not too long ago published this sort of like the rules of this, of the special projects that you do. And early on in that list, you say, let me be really clear here. This is about me making books. Yeah. This isn’t about me managing a community. No, it’s beautiful and also really contrarian.

Craig Mod: [01:02:25] That’s how you have to operate if you want to be a quote unquote artist or, you know, kind of untethered, creative person in the world, you have to be militant about protecting space for you to do your work. The membership program started in 2019, January 2019, and it just kind of came out of frustration with not being able to sell bigger articles to bigger magazines. And I had a whole set of writing I wanted to be doing, and I didn’t know how to do it in the sense of I was never trained to be a long form writer in magazines or whatever. And like I’d done all these writing residencies, but it was all kind of fiction. I was just having a really hard time selling these pieces, and I finally just hit this wall and I was like, fine, I guess I’ll do a membership program because it was right around when everything was kind of emerging. Substack was courting me like crazy back then. They really wanted me to join, but I don’t like constricted spaces, and so, like, Patreon wasn’t interesting to me. Like, I like feeling as a creative person, unrestricted in I love rules, but I love when they’re my rules. I don’t love it when some other ding dong is making the rules for me.

Jonathan Fields: [01:03:30] I love rules as long as I said them.

Craig Mod: [01:03:32] Yeah, I love them and I love setting them. And I love and I love sticking by them until I don’t want to stick by them anymore. And then I’ll make more rules. But. So I ended up building my own system, using Memberful to do payments and stuff like that. But it’s Memberful is very open, and back then it was even more barebones. It was really just this kind of NPR style, like, I’m literally giving you nothing. You’ve just been reading my work for, say, 12 years and want to support me, and I’m going to just try to be more radically independent now. That was kind of the pitch. And so it started with that. And then, like I said, my first big walk from that was the Nakasendo walk, and that really unlocked the sense of power that a community supporting you financially can bring to your work the kind of permission that comes from that. And I’d say that was that’s been the biggest thing I’ve divined from this community is permission. And that first year I didn’t have a cohesive manifesto. I didn’t have rules, really. I just wasn’t going to make anything. I knew that from the beginning. I didn’t want to make things just for the community, because I didn’t want to get caught in this catch 22 of like, you’re doing a community to make your work, but you end up making work for the community, and so you don’t do the work you want to do in the beginning, like that’s what you want to avoid. And then that second year, 2020, when Covid hit, it put the brakes on, like me traveling anywhere.

Craig Mod: [01:04:51] I was like, okay, well, let me do a book, because that one off book I did with the responses from everyone was so powerful to me. And it reminded me, because in my 20s I’d been making books, beautiful books. That’s how I connected with John. And then in my 30s, I sort of stepped away from books a bit. I was kind of focused more on my own craft. I didn’t want excuses to not be writing, and so I was spending all of my time doing residencies and just living in my, my craft. And I was like, well, maybe. Yeah, you know, I do love, love, love books. And I want to like, what if I went back and on my own, entirely independently, on my own. Because in my 20s I had a kind of a business partner, and we were running this publishing company, and I was like, what if I did this completely on my own, where it’s just me? And we really went crazy because it’s Covid. We can’t do anything anyway. Like, just try to make a really beautiful book. And I leaned into that. And then that book priced at 100 bucks, I thought based on my my history in publishing, I was like, okay, this will take me a couple of years to sell a thousand of these. And I wanted to be able to offer a discount, a coupon to members and the membership program. I was like, okay, this will be the first like, membership perk.

Jonathan Fields: [01:06:00] Beyond just like patronage. Thank you for doing what you’re doing.

Craig Mod: [01:06:03] Yes. It’s like this is like going to be the first tote bag, the first NPR tote bag. And I was like, okay, I want to offer a discount to members, especially early members who are paying me 100 bucks a year. I want to give them a discount. And I looked at Kickstarter and like, you couldn’t do you couldn’t do coupons with Kickstarter. And I was like, this is bullshit. I looked at Shopify for the first time ever in my life. And I wish I looked at it earlier because I would have bought Shopify stock so much sooner. Like, it’s just such a good product. I was blown away by how freaking good Shopify was. And I was able to build this is pre LMS pre like code helpers. I was able to build a Kickstarter clone called Craig’s Starter in Shopify. Over the course of like a week, I was like, okay, this is cool. And I could do coupons and da da da. And so I launched that and it was just bananas. The we sold out in two days a thousand copies of that first edition, which I was just like, wow, I didn’t think that was going to happen. And so many people joined the membership program to get that discount. And I just realized there was this incredible potential for even deeper symbiosis between me wanting to produce this work, which to me felt like just the apotheosis of giving shape to what I was doing, and then people wanting to support that and support me as a patron and get a little kickback with the discount. Like that was just. Whoa. Okay, that was not planned. And then in that moment, it was like everything reconfigured itself and it was like, okay, this is what we’re doing for the next 20 years.

Jonathan Fields: [01:07:31] When you say a book, by the way, because people heard you say $100 for a book, like, wait, what? We’re talking about a book that is a beautiful like, literally, it’s a work of art. It’s a it’s a very small, limited run. So it’s this is like a limited edition piece of art. Like, this is something that’s extraordinary. Um, that said, and you having a really strong like, as you used that word earlier in our conversation, uncompromising aesthetic when you’re like, okay, I’m going to put this first thing out into the world. The typical book is like, you know, the actual price is 26 bucks, but people end up paying like 15 to 20 bucks. I’m charging $100 for this. And yes, it’s a special book and it’s and it’s beautiful and it’s handmade and nervous about that at all. Were you freaked out about it at all or were you just like, this is this is what this is worth?