What if pursuing mastery wasn’t the goal? What if there was profound joy, meaning and even transcendence in being intentionally average at something you love?

What if pursuing mastery wasn’t the goal? What if there was profound joy, meaning and even transcendence in being intentionally average at something you love?

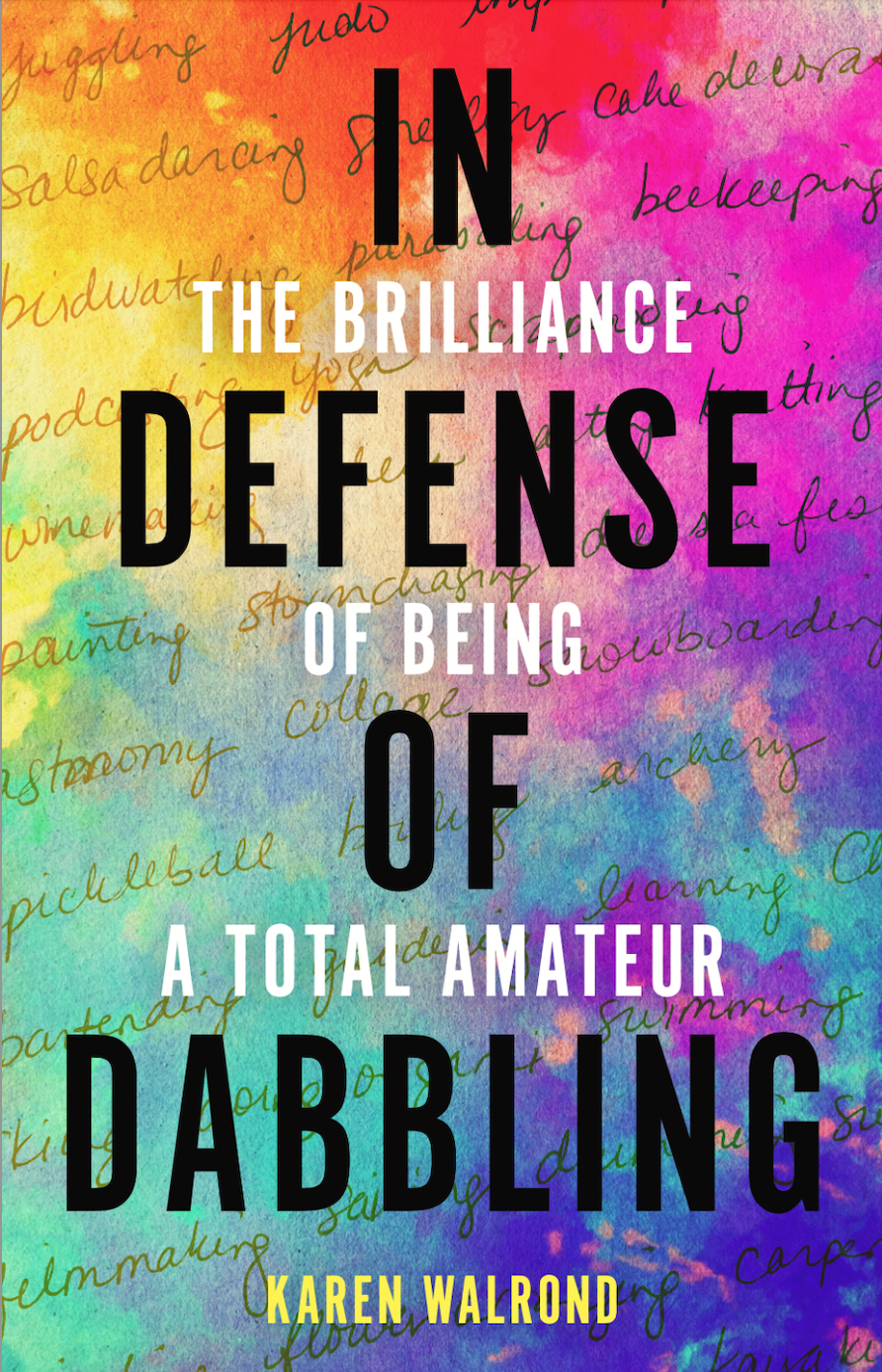

In this illuminating conversation, leadership consultant and author Karen Walrond shares a revolutionary perspective on hobbies, creativity and personal growth from her new book “In Defense of Dabbling: The Brilliance of Being a Total Amateur.” She reveals the seven attributes that transform simple activities into portals for self-discovery, from mindfulness to wonder.

You’ll learn why letting go of excellence can lead to greater fulfillment, how “intentional amateurism” builds resilience and self-compassion, and why community forms naturally around shared interests. Karen explains how activities like pottery, surfing, or metalworking become spiritual practices when pursued purely for joy rather than profit.

This conversation challenges the cultural pressure to monetize every passion and offers a refreshing alternative pursuing activities simply because they light us up. Whether you’re considering a new hobby or questioning the need to master your current ones, this episode provides permission and practical guidance for finding profound meaning in being perfectly imperfect.

Perfect for anyone seeking more play, creativity and authentic self-expression in their life, without the pressure to turn it into a side hustle or achieve excellence. Join us to discover how being an enthusiastic amateur might be exactly what your soul needs right now.

You can find Karen at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with James Victore about making your art and owning your point of view.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:00] So what if the pressure to master everything, be excellent at it, or even just one main thing was actually holding you back from experiencing genuine joy in your life? What if being intentionally not great at something or many things made you way happier, more fulfilled, and in love with your life despite being told that it’s a road to mediocrity and slackerdom. What if mediocre was actually pretty awesome? These questions sparked a fun and eye opening conversation that challenges everything we’ve been taught about hobbies, creativity, passion, side hustles, careers, and personal growth. And the answers might transform how you think about what makes life worth living. My guest today, Karen Waldron, is also a dear friend and sometimes collaborator and author, leadership consultant, speaker and photographer who helps people live better lives. She’s trained in positive psychology coaching with the Whole Being Institute, and has written multiple acclaimed books. Her latest in defense of dabbling the brilliance of being a total amateur offers a provocative and welcome new perspective on the power of what she calls intentional amateurism. In our conversation, we explore the counterintuitive idea that being mediocre at something that you love can actually lead to greater fulfillment than striving for mastery. And Karen offers really practical wisdom for anyone feeling the pressure to monetize every passion or turn every hobby into a side hustle. We also dive into seven surprising attributes that can turn simple activities into portals for self-discovery and joy. And Karen shares how letting go of the need for excellence opened unexpected doors to joy and community, and even becomes a potential spiritual practice. She reveals why activities like pottery or surfing pursue purely for pleasure might be exactly what our souls are craving in this achievement-obsessed world. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:03] I would love to start with five true false questions. You are going to be inclined to want to answer way beyond true false. I’m going to ask you to just see if you can hold back whatever is bursting to get out and give me a true and a false, and I promise we will make our way back to them and deconstruct them in a lot more detail. Sounds good. Number one, if you’re not working towards excellence or mastery, you’re just wasting your time. False. Two. Sucking at something can feel as good, if not better than be amazing at it.

Karen Walrond: [00:02:37] 100% true.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:38] Three. If a hobby or passion won’t eventually make you money, it’s just not worth the effort.

Karen Walrond: [00:02:44] False.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:46] Okay. Four. Play time is critically important to adult mental health.

Karen Walrond: [00:02:52] True.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:53] All right, last one. It’s more rewarding to devote yourself to a single, deeply passionate pursuit than to spread your energy across many?

Karen Walrond: [00:03:03] Oh, wow. I have to pick true or false? Um.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:08] All right. You can say it depends.

Karen Walrond: [00:03:10] I’m gonna say it depends. Yeah. I’m gonna say it depends on that one.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:13] All right, we’ll dive into that. Let’s talk about each one of these a little bit now. Um, okay. Number one, if you’re not working towards excellence or mastery, you’re just wasting your time. We have all heard some version of this from parents, teachers, people who only wanted the best for us, sometimes our own internal voice. We may have uttered this exact same thing to our children.

Karen Walrond: [00:03:36] So.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:38] Um, you say this is false. Take me into this.

Karen Walrond: [00:03:42] Well, let me start with a preface that I’m not saying that we shouldn’t work hard at things, right. Like, for sure, there are certain things in our lives that we have to work hard at, that it will behoove us to work hard at, like your maybe your job, certainly parenting. Certainly things like that. Like you want to work really, really hard. What I posit and what I think is true also, is that we’ve gotten to a point in life, in our culture where that’s the only thing we should be doing. And I think it’s actually exacerbated by social media. Right. And sort of seeing people do things online like, well, if they’re so great at it, then I shouldn’t even try it because I would never be that good at it. What I found, certainly over the last year and a half of working on this book, is that there is so much joy and self-compassion and self-transcendence that can come from doing something purely for the love of doing it, not doing it for profitability or perfection, but just doing it because it’s fun. And originally, I think when I first started writing In Defense of Dabbling, I thought it was just going to be a lighthearted book about hobbies. And what I quickly realized is that no, no, no. Having something that you can keep going back to just for fun. Having a cadence of returning to it is all about self-care, self-compassion, self-transcendence and it’s just good for us.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:05] Yeah, and you know, it’s interesting because I want to disagree with this in a weird way. I have had the experience where I’ve focused on something and or on a couple of things, and I was like, all right, I’m going to make a long term commitment to this. And part of what I wanted to do was get really good at it. Sure. You know, and so I poured myself into it. I worked really hard, and I did get really good at it. And what I learned was that the feeling of doing the thing is really cool. The feeling of being really good at it is also really cool, but in a different way. And when you add those two together, it feels pretty amazing. But I think you’re right, you know, like we tend to get caught up in the doing the thing for the purpose of becoming amazing at it. And we sacrifice so much of just the experience of doing it along the way, because we’re waiting for that feeling of being amazing. We’re waiting for the feeling of excellence and mastery. Maybe it comes. Maybe it doesn’t. But what we’ve done is we’ve given up so much of the joy along the way by focusing only on the outcome of excellence. And I agree, there are so many signals out there in the world that sort of like, say, this is what we should strive for, and anything less is kind of a waste of time and energy.

Karen Walrond: [00:06:13] Yeah. And I think, I think, you know, in some ways the idea of pursuing intentional amateurism, like the idea of pursuing something just for its sake. I really believe that if you have a practice of going back to something like constantly, like you’re constantly whittling or running or whatever it is that you’re doing, and you keep going back to it, naturally, you’re going to get better. Right. And naturally, you’re going to like, sort of surprise yourself with what you’re able to do and what you’re not. And that’s a great feeling. But I think what we need to do more of is focus on the now of doing it and how it feels to do that in the moment. And they’re going to be let down. Sometimes you’re not going to do great, but that whole sort of curiosity into your own evolution as opposed to I’ve got to get to that, to X brilliance. It’s invigorating, it’s energizing, and it’s a really it’s it’s a lovely thing for you to do for yourself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:15] So here’s my question then. If we are not actively pursuing excellence in something, do we risk becoming slackers and just phoning like spending so much of our time phoning it in? And is that actually a bad thing, if that in fact is part of our the truth of that?

Karen Walrond: [00:07:33] Remember, what we’re talking about here is an avocation is something that’s just for fun, right? If you become a slacker in something that there’s no repercussions, right? There’s no repercussions. If I decide that hula hooping is my thing that I want to do, right? Like, if I fail at it. If I become a slacker at it. So what? It’s a hula hoop. It’s not a big deal. It’s not my job. It’s not parenting. Right. So, yeah, I would argue that depending on what you choose and what we’re talking about is choosing something that you’re not going for profitability or perfection. Right? It’s it’s just something that’s fun. There’s no repercussions other than the fact that maybe you’ll tap into some curiosity or some mindfulness or some play and all of the benefits that come from doing that sort of thing. Like to me, that’s a win, right? Whether or not you become the best Ted talk speaker or whatever it is that you choose that you’re going to be doing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:27] That’s so funny as you’re describing that, like at a vision of Jeff Spicoli from like, that classic 80s movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High, the ultimate slacker, and like, how happy he perpetually was just living his life, right? Yeah. Granted, he was a little bit baked for most of the day, but that’s a whole different issue.

Karen Walrond: [00:08:44] But that’s a whole different thing. And also like, I mean, it’s one thing to like, I would not suggest doing this for something that you have to earn a living at. Yeah, right. Like that. Like, no, no no, no, you really should work hard at your job, or you should work hard at your partnership. I’m talking about the thing that you intentionally step away from the responsibilities of your life, from the crazy that is the world, to just focus on your inner joy, right? Your inner love. And what’s really funny is like, the question that I seem to keep getting is like, well, what about commitment? Isn’t being an amateur? Doesn’t that require a certain amount of commitment? And what I’m talking about here should not feel like a chore. Like if it starts to feel like a chore, that’s probably not your thing, right? It should be the thing that you’re itching to do. Like, for my husband, he’s a mountain biker. That’s his intentional amateurism. And if he’s not on his bike 4 or 5 days, like he becomes really cranky. Like it’s to the point where it’s like, oh, please go, go ride your bike. You will feel better if you ride your bike. That’s the kind of thing I’m thinking about, is the thing that you’re just like, so itching to get back to that, the idea of, oh, I haven’t done it and now I must go back. Like it shouldn’t feel like that. That’s not what we’re talking about.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:55] Okay.

Karen Walrond: [00:09:56] But oh, oh, we’re devil’s advocating today. Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:01] We both have our, like, our ancient lawyer’s hats on. Exactly. It’s like, here’s what’s coming up for me. I’m. I’m a writer. Okay. So yes, in part, I get paid to write like I am an author. I get paid for different types of writing. And I have for a long time. I’m very blessed in that way. Yeah. And still, there’s plenty of writing that I do that has nothing to do with getting paid for it. Like the book that took me the longest. It took me four years to write a book, which I wrote to one person, you know? So writing is a part of me. Writing is that thing. It is that I keep going back to. And yet there will be many times where I go back to it, and it feels like a chore to me. It feels brutally hard. I don’t want to do it, even though I know that there are enough times that when I’m doing it where I feel like it is, I get lost and I get giggly because I’ve just figured out, like three words that fit together in a really beautiful way. That took me ten years to write, but a lot of times when I’m doing it, and maybe for me, there is, I am really locked into the pursuit of excellence with that particular thing. And yes, maybe part of it is that I get paid to do it, but I do a lot of writing where it has nothing to do with getting paid. I don’t ever expect to get paid for it. Sometimes it feels amazing, but other times I show up to do the activity and it does feel like a chore.

Karen Walrond: [00:11:12] Yeah. Who’s the writer that said that? I hate writing, but I like having written.

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:16] Like, I can’t remember who that was, but.

Karen Walrond: [00:11:17] I identify with that so deeply as well. Like, I find writing a really excruciating thing when I’m writing a book, but like, I have a Substack and I write things all the time that have I write on Instagram, right? Like there’s I write things all the time that have nothing to do with it. But for me, writing is while it can be fun, it can be excruciating. Even the fun stuff that I don’t do for pay that for me, feels like honing my craft. That feels like the stuff that I’m doing that ultimately is about the craft of what I’ve chosen to make my profession around. Right. Let’s take photography. So I’m a photographer. I’m an avid photographer. I’ve been shooting for 30 years. I love photography, and I’ve made a very pointed decision to never accept money for it. Because for me, when I do accept money or when I have accepted money in the past, it does suddenly feel like a chore. And I don’t want photography to ever feel that way for me, because that is the thing that I do that is 100% for just fun. So I would argue that maybe that writing is not your intentional amateur thing. It may be something. I mean, I know you live in Boulder, maybe it’s snowboarding, or maybe it’s something that has nothing to do that you just don’t get paid for at all. And the writing that you do for fun is merely sort of you’re honing your craft, right? Like that’s part of what you do to do what you do for a living.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:38] Yeah. I would then submit that, um, probably the purest expression of intentional amateurism for me is eating chocolate, because I never feel like that’s a chore, Sure ever. I will for my entire life. That will never be a chore.

Karen Walrond: [00:12:51] I mean, as long as you don’t get to the point where you’re eating so much chocolate that you’re starting to feel.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:56] There are risks there.

Karen Walrond: [00:12:57] Yes. Yes, But yes, I mean, I too. I’m not. I don’t have a sweet tooth, but chocolate can get me. And yes, I think that’s a noble avocation for you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:07] Okay. So we’ve been kind of referencing that third true false that I asked you also, but let’s speak to it a little bit more directly. And that was if a hobby or a passion won’t eventually make you money, it’s not worth the effort. And you said decidedly false.

Karen Walrond: [00:13:19] If a hobby doesn’t make you fat. Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:21] If a hobby or passion won’t eventually make you money, it’s not worth the effort.

Karen Walrond: [00:13:25] Absolutely. One of the things that I found again when I started writing this book, I thought it was just going to be this light book on hobbies. And one of the things I realized quickly was when we think about the things that are good for you, I’m using air quotes, right? Like one of the things that they always tell you in addition to, like working out and eating right is like you should have some sort of spiritual practice. You should meditate for 30 minutes a day, or you should do yoga or something like that, which I think is wonderful advice, except I’m really bad at both. I don’t have the patience to keep coming back. I’ve got my mind goes in crazy places. But I have found, for example, when I’m doing pottery, my mind quiets. I focus on the moment in front of me because if I don’t focus, the clay is going to go flying off the wheel, right? Like all of the things that they tell you that are really, really good for for your spirit, for your mental health, for all of these things you can find in pursuing a hobby. Right. That thing that you lose time with, that you have to focus on, that you forget about the outside world. All those benefits that you get from maybe a yoga practice you can get from doing something that you naturally do anyway. And I think for those of us for whom a spiritual practice can feel like a chore, it can feel a little bit more challenging. This is a nice, easy way into getting into some of those benefits.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:46] Yeah, I totally agree with that. I think there’s a value that’s often passed on to us. Or again, we absorb it just from the zeitgeist that says we already have not enough hours in our day to do all the things that we’re supposed to do, and we’re going to allocate some of that time to something else. It really needs to have some sort of value associated with it. And the value tend to lock into is it earns money, right. You know, so it’s like you can’t just have a thing that you love to do on the side. Like the next question you must ask is, how do we turn that into a side hustle for sure. And I think sometimes that’s fine. But other times it’s not only not fine, but it’s actually kind of destroys the whole reason that you’re doing it in the first place.

Karen Walrond: [00:15:26] Absolutely. Like if the whole point you started was because your job is so stressful, then why would you want to have another job, right? Like by turning it into a side hustle like that can be really, really tough. That’s not to say that maybe you need money and you have to have another job, but that’s not what we’re talking about here. We’re just talking about what do you do to unplug, to be with yourself?

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:48] Yeah. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. I’m going to bounce back to that second to false statement.

Karen Walrond: [00:15:58] Okay.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:58] Sucking at something can feel as good, if not better than being amazing at it. This is kind of counterintuitive for a lot of people. And you said, yeah, this is actually true.

Karen Walrond: [00:16:09] Yeah, it is true. And I will I my as evidence, I go to my pottery practice. I’m really bad at it. Right. Like like I am I am not good at it at all. I’ve been doing it now for about a year and a half. I make decidedly mediocre pots, but I’ve also made the commitment that I’m never, ever going to take money for them, right? So what ends up happening now is when I go to the pottery and I’m, I’m sitting in front of a lump of clay because I am freed of I need to be perfect at it. I need to be great at it. I get to settle into a sense of curiosity about what’s going to happen in the moment that I do it. If I fail, if it falls apart, if it slumps, I get to be curious about what feelings did that bring up for me and why did that bring up for me, especially for something that’s not making me money, that there’s literally nothing. There’s no repercussions about the fact that it failed. And it’s a really lovely practice of getting to know myself. Right. I don’t want to sound like the Zen monk on the mountain every now and then. Like just the other day, it fell apart and I smashed it really hard. And I was really, really upset by it. But overall, this pottery for me is the thing that allows me that when I’m stressed that I can come to and calm. And I’ve found, interestingly, that when I fail at pottery, it’s usually because I have not let go, right? Like I’m still working through that. And they always say in the pottery, the clay knows, right? It knows your mood. And so like, you got to slow down, you’ve got to stop. And so that kind of thing has been really, really interesting for me. That’s the benefit of the pottery. Even if I’m making ugly little pots that I foist onto family members.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:52] Yeah. I mean, it’s interesting and we’ve talked about this off mic. I’m taking Metalsmithing classes now and I’m still a total newbie. Like absolutely terrible at it. Yeah, I was in the studio this was last week actually, and I was learning how to do just a really, really, really basic thing, something that is like newbie 101 type of thing, and it required bending metal and it required using oxyacetylene torch and heating something. And once you once you did it, once you soldered it, you can’t easily undo that. So I did it and I brought it back to my teacher and I showed her and she’s like too big. Got to redo it. So I literally had to redo this one thing and rebuild the entire thing three times.

Karen Walrond: [00:18:33] Wow.

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:34] And getting to the third time, I’m thinking to myself, like it was weird that I noticed that I wasn’t getting frustrated.

Karen Walrond: [00:18:41] Right!

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:41] I was wondering why? Because I’m like, there are plenty of other things in my life where like if I have to redo something three times, I am beyond annoyed. Yeah. And I was just in it, and I was just like I had forgiven the fact that I needed to be anywhere but the level of proficiency or total lack of proficiency where I was in that moment. And I just wanted to learn. And there was something like really magical about it.

Karen Walrond: [00:19:06] Yes. Exactly. It. There’s something about failing that becomes I, you know, somebody I interviewed in the book says this. There’s something about failing that becomes very fascinating when there’s no repercussions for what you have to do. Right? You’re like, oh, why did that fail? And how did that fail? And how am I going to get better at it? And how can I save it when I can see it’s falling apart? And how can I fix it? And that’s a really we don’t get a lot of opportunities to do that in life where there aren’t repercussions, right? But what ends up happening is that resilience that you’ve practiced by having to do the metalsmithing 2 or 3 times. How magical would that be? That you could take it into your real life? Right. Because now you’ve been sort of exercising that resilience muscle, and now maybe you can take it into your real life when there are repercussions, like, how do I bounce back when something doesn’t go my way, and how do I fix this? And how do I tap into that feeling of curiosity that I had in the Metalsmithing studio, as I’m dealing with this project in my real life?

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:02] And, you know, like as I was doing this, I came out and the next day I was telling somebody I was doing this stuff. And their first question to me was like, oh, like, are you are you going to sell sell your work?

Karen Walrond: [00:20:12] Yeah. Are you?

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:13] No.

Karen Walrond: [00:20:14] [laughing]

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:14] I mean. I mean, look, I can’t say never, you know, but that’s not it’s not my intention. My intention right now is just to show up and do the thing because of the way it makes me feel and nothing else. Maybe someday. And you’re, like, by a thousand years, I’ll be good enough to actually sell something. And maybe at that point I won’t even want to, you know, because of the same reasons that you mentioned. But my knee jerk reaction, as soon as that person said it to me and they weren’t, they were just genuinely curious. They weren’t just like, but I felt I was like, there was a shift where I was like, that’s going to mean I’m going to show up to the studio and do it for a different reason, and I don’t want that.

Karen Walrond: [00:20:48] Yeah, I know. There’s almost like a real resistance that you probably felt. It’s like like, how dare you even suggest such a thing, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:56] Well, and I also wanted to say, if you can see what I’m making right now, you wouldn’t be asking that question, but.

Karen Walrond: [00:21:01] Well, you know what’s really funny? What I found for me is, I mean, I’m really, really mediocre at this. And there are people who took that first pottery class with me that have gone on to do much more intricate things than than I’m able to do. But I did get to a point where, like, I shared something online and somebody said, I would really love to buy that, right? And because I’ve been spending so much time in the pottery and seeing other people work, like I know that I will be able to do so much better than that, right? But it’s so funny how people will ascribe sort of a value to something and you’re like, oh no, no, no, no, no, this is not something that I would feel comfortable accepting money for. And I’ve said that before. I’m like, I could just see, like accepting money. And then five years from now I go back and I’m like, I cannot believe I took money from this person for that thing, because you’re so much better at it. And just having that thing where the, the whole goal of it is just to watch your own evolution in your own time, in your own space, for no goal like that’s a gift to be able to have something that you can do that with. Right? And to be clear, like, I mean, I’m sure Metalsmithing is not the cheapest hobby you could have. Certainly pottery isn’t, but I’m not talking about expensive things. It could be running, it could be stargazing, it could be anything that you want that you suddenly realize, oh, you know, I was interested in the stars. And now I go out into the desert and I know all these constellations that I didn’t know six months ago or whatever. You suddenly realize what you’re learning. It’s transforming the person that you were when you first became. And that in itself is just such a lovely journey to be on with yourself, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:40] Do you think it’s possible to start something, to be a dabbler, to be an intentional amateur, to do it, to immerse yourself in it, to commit yourself to it over time? In the early days, especially for no other reason than the feeling it gives you, you just really enjoy doing it. And over time you start to get better. And then then you do reach a point where what you’re making is sellable, and then maybe you’re just at a point where it’s like, well, like I actually feel like there’s that’s comfortable. People want it, there’s value in it. We get to share something here. Do you think it’s possible to hold on to the original feeling that brought you to it, the early days, if and when? At some point you do turn the corner and say, I’m going to actually accept money for this.

Karen Walrond: [00:23:24] Hmm. That’s such a great question.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:26] Because I think a lot of people will, like, will hit that moment, probably.

Karen Walrond: [00:23:30] I will say in my experience, it’s extremely hard to do that because especially when you start to if it’s an art, like if it’s an art form, you have to take people’s feedback or you often have to take people’s feedback into consideration. So, you know, like I, I see people at the pottery that are like, well, I like that, but could you make the handle different? Or in photography it’s like, well, I love that, but could you Photoshop that out? Right? And it starts to not feel like your own full art, right. Because somebody else is telling you. So in my experience, it’s a really difficult thing to do. That said, I think that it’s possible if you challenge yourself to experiment somehow with that art in a ways that maybe that you don’t sell. So one of the things that I tried in the book was filmmaking, right? And after 30 years of photography, I thought filmmaking is going to be an absolute breeze. It’s totally not. It’s a complete things move in film, right? But it’s been really fun. Now, I don’t accept money for for photography, but I could see that maybe if I were a photographer, like going into this other realm where it’s a little bit different and I’m really sort of a beginner again, and playing with that and not accepting money for that aspect of using my camera, I could see potentially that would do it. But the whole point of amateur is to do it purely for the love of doing it. It’s not supposed to be for profit or so to me. Once you start to accept money, that becomes a whole different thing. Whether or not you love it, it’s just a different thing. It’s not the same.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:59] I remember reading Mason Currey’s original book, Daily Rituals, where he sort of like, revealed the daily rituals of like a whole bunch of really well-known artists and writers and people like that. And actually his brand new book coming out, I think it’s something like making money making art or something like that. I can’t remember exactly what it is, but a lot of the examples that he would give were people of like where they became super well known for their craft, for their art, but many of them had day jobs. They worked for the postal service. They had like fairly straightforward, reliable, secure, you know, day jobs. And many of them never had any desire or intention of leaving. Some did want to leave, but many were like no, no, no. This allows me to go to that other place where when I create, I don’t have to create with anyone in mind or appealing to anyone’s aesthetic sensibility than mine. And that allows me the freedom and the power to really just express who I am, what’s in my heart, my own sense of taste, and if it resonates with people outside of that. Cool. And for many of them, it eventually did, and actually at a much higher level than their sort of like their core job. But it gave them the freedom to go to a place that they never would have have gone had there been a commercial aspect of it from the beginning. I thought it was interesting.

Karen Walrond: [00:26:15] Just think about also like, I mean, I think you and I have both been online for a long time, right? So think about like when blogging first happened, or even when Flickr or Instagram first happened. It felt like a place where people were just sort of experimenting, right? There was no such thing as monetization. There was no such thing, right? People were just writing, and people were just sharing. And think about what the community or the body of work that was being put out compared to what it is now, where everybody seems to be an influencer. Right? You’re constantly talking everybody. It doesn’t even matter if people make a living at it or not. They are sharing pictures of their kids that are ultra curated. And there is something that changes. I think sometimes for the good, sometimes not, but something that changes when you’re making it for other people, right? When you’re doing something for other people, it’s a different animal. And I think intentional amateurism where you’re practicing what I call the seven attributes, right? Curiosity and mindfulness and play where it’s solely for you. I mean, certainly you might be doing something with somebody in the book. I was sailing with my husband, and so surely it was doing that, but it was not for the public at large, right? It wasn’t for people at large. And there’s a different feeling that happens when you’re focusing on doing something just for yourself.

Karen Walrond: [00:27:30] Mhm. So agree with that. It’s more rewarding to devote yourself to a single, deeply passionate pursuit than to spread your energy across many. This is kind of related to the opening one where it said it’s better to pursue mastery, but this is more about just focusing on a single thing. And again this is what’s so often this is the message that has been given to us. You pick your one thing you do. You pour every ounce of yourself into the thing, and every other thing that you do makes ensures that all of them never get the level that you want. And to a certain extent, like this is not entirely untrue.

Karen Walrond: [00:28:09] Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:10] But it’s often again always said in the context of something more professional.

Karen Walrond: [00:28:15] Yes, I think I answered it sort of depends on this one, right?

Karen Walrond: [00:28:18] Yeah.

Karen Walrond: [00:28:19] In the book, I talk about what I consider dabbling, which is like trying a bunch of different things and seeing how you feel when you do them. And that’s what I did. Throughout the book, I try seven different things, ranging from playing the piano to surfing. And then I talk about intentional amateurism, which is the returning to the thing that you really love. And I think there’s value in both of those things. I think if you found the thing that really is energizing and calming and self-compassionate and self-transcendent and you want to focus on all of that, I will be the last person to tell you to stop doing that, right. But I also think that trying a bunch of different things to see. Does that sound fun? Is that. Does that seem like a part of me that I’ve never explored before, that I’d like to see that. For me, that was surfing. Like, I’m not a surfer. I love the ocean, but I’m not a surfer. But it was such an exhilarating experience to try it and to discover a part of me that likes to surf and can actually stand up on a board, which, who knew that was possible? Like, that’s really, really fun to. And it has its benefits. So that’s why I was sort of like, yeah, I don’t know how to answer that one about true or false, because I think there’s benefits in both. Ultimately, it’s about focusing on how to take care of yourself through doing something that you love or finding the thing that you love. And I think that that’s more important than whether or not you do many things that you love or one thing that you love.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:42] I mean, that really lands with me. It’s almost like a yes and yes. Maybe you actually just stumble early in life, even on a thing where you’re just like, yeah, for for some reason, I can’t understand. It just feels amazing. It’s probably never going to be my career, but I just love doing it. And I just want to spend all my time doing that thing. I found that to be the rare case. I think a lot of us have to try a lot of different things, and maybe we end up with 2 or 3, maybe we end up with one. And I think it also can depend on the person. I think some people they’re happier with, like an assortment of things they can rotate between. And some people just want that one thing where they can really deepen into it.

Karen Walrond: [00:30:19] One of the things that I talk about in the book also is, you know, you you said sometimes people early in life might stumble on that one thing. For me, I thought that was piano, right? When I was a kid, I played piano all the time. I played even after I stopped taking lessons. I would teach myself more things, and I returned to it in the writing of this book. And I did it and found out like, yeah, I’m good. Like, like, I really don’t need to do that. And I thought that was really interesting. And maybe it maybe it speaks to the fact that I’m just not the same person I was when I was 15 and playing the piano all the time. But that was in itself was a really interesting discovery, because I really thought that once I had devoted some time to practicing piano again and doing it, that I would suddenly fall in love with it again. And it actually didn’t happen. It was like, yeah, that’s cool. I learned a piece and I’m good. I don’t need to sit at the piano anymore. Um, that feels a little bit like a chore.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:13] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. So the phrase intentional amateurism, you’ve used it a number of times now. How do we actually what is what how do we define this? What is it?

Karen Walrond: [00:31:28] Yeah. So for me, intentional amateurism is literally focusing on something with no intention of becoming a professional at it, with no intention of turning it into a side hustle or turning it into something that I’m recognized for, or that you’re recognized for, and really trying to stay out of perfectionism. Right? Because I think especially in the rest of our lives, we do have this sort of message that we’ve got to excel the whole time. And so I came up with what I call the seven attributes of intentional amateurism, which is if you’re tapping into these things, you’re probably doing it right, right. So if you’re tapping into things like play and it feels like play where you lose track of time and you’re having a great time doing it, or it feels self-compassionate, or it feels like you’re scratching a curiosity itch, or you’re tapping into wonder and awe. Like if you’re doing those things, then you’re probably doing it right. Because if you’re focusing on that, you’re not focusing on the perfection of it. If you’re focusing on those things, you’re not focusing on, well, how can I turn this into an income stream or whatever it is? So it literally, for me, is intentionally returning again and again and again to something without feeling like you have to be perfect at it.

Karen Walrond: [00:32:44] And I was actually really surprised at how difficult that was for me, which is why I came up with those parameters. It was also really difficult to find people who do it, because most people, if they’re really good at something you already know about it, and they may be really finding friends who were doing things that I knew about and suddenly realizing that they had this other little secret life where they were making automata was one thing with like little robot things that the one woman did, um, weaving was one other person. There was a watercolor and all of these things that I, these secret lives that these friends of mine had that I actually didn’t realize that they were doing and it it took a moment to find them, but to a person they were they were all like, I don’t know that I could do my regular life if I didn’t have this practice of intentional amateurism to help return me to myself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:33:38] Yeah, it’s like a grounding practice. I mean, you also and this is something you write about, you describe it also in a way as a spiritual practice, 100%.

Karen Walrond: [00:33:46] And I did not expect that, especially the things like wonder and awe. Right. Like when you think of of wonder and awe, which is that the seventh attribute that I talk about, you think of things like, oh, you’re studying the universe or contemplating how interconnected we are. Now for that practice, I did try to photograph the universe. I tried to photograph the Milky Way, but what I found actually in my own life in the pottery, which is the one that really stuck for me, is in addition to the curiosity, the mindfulness. One of the things I think about all the time is the fact that I am now practicing an art that has been practiced for millennia, that archaeologists literally look for shards of pottery as evidence that a civilization was once here. And to think of myself as now being a part of this community of people that has existed for millennia. That’s the wonder and awe for me. Right. And so it’s really interesting how you think about, oh, I’m part of this tapestry of humanity that has existed forever, or I’m part of this little tiny dot on this little tiny planet hurtling through space, or whatever it is that taps you into a world that is bigger than you are. I mean, that’s the ultimate, right? And that’s very self-transcendent. And it is very spiritual when you start to practice that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:03] Yeah, I can totally see that. It’s like you become without intending, you become part of a lineage, and you become part of a conversation that will both go back in time and can be carried forward in time.

Karen Walrond: [00:35:17] Absolutely.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:18] Which does have this sort of transcendent element to it. You brought up a number of times also these seven attributes of intentional amateurism. We kind of like dance around some of them, but let’s dip into them, because I think one of the questions people joining us are going to have, okay, so how do I know when I’m doing the thing. And this is basically your answer to that. Like these are the qualities where you say like when I’m able to dip into these seven different qualities, it’s a really strong signal that I’m doing the thing that I’m doing this thing that will give me the feeling that I want to have. So let’s walk through them a little bit more intentionally. The first one is curiosity.

Karen Walrond: [00:35:53] Curiosity is not just about it sort of scratches that learning edge. I want to find out more about something, and it could be the practice of metalsmithing, but it can also be how you change and how you react as you’re practicing the metalsmithing. So it’s about this constant like what would happen if what happens if I do this? What does that mean with me when I do this, That curiosity thing is really, really important. And I want to be clear as we go through all seven of these, like the thing that you pick may not hit all seven, but it probably will pick a couple of them, right? 1 or 2 when you do them.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:31] Yeah. It’s like they’re signals.

Karen Walrond: [00:36:32] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:32] It’s interesting. Right. Because I would imagine for you, as you said, you tried a whole bunch of different things. So you gave yourself the ability to see what was repeating, what patterns were recurring as you were doing the different things, and you were really intentionally observing. What are the feelings that I’m having in order to see like, okay, so what are the things that keep bubbling up when I have this feeling and want to keep having, rather than just like saying, trying to deconstruct a single activity?

Karen Walrond: [00:36:55] Exactly right. Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:57] That takes us to mindfulness.

Karen Walrond: [00:36:59] Yeah. So mindfulness I think when I first and it’s really interesting because a couple of times what I had in mind, the attribute was going to be sort of shifted. And I think for mindfulness, I think this one was sort of like losing consciousness of the outside world. Right? Is what I originally thought it was. And I was like, oh, this is really about mindfulness. And for me, mindfulness is the thing where you really focus on the present moment, right? Of whatever you’re doing, it allows you to do that. I started a swimming practice. Right. Because I figured if you’re not focusing on your swimming, you will drown. And I’m not a strong swimmer. As a matter of fact, I’m a really poor swimmer. But I thought, well, let me see how it feels to go to the pool, which I don’t particularly like. I’m an ocean person and just swim and see what happens. And it was really transformational because I went in with a little bit of resistance. And what ended up happening was this the rhythm of doing the strokes and going back and forth in the water was allowed me to not only focus on exactly what I was doing, but sort of let go of the thoughts that were going in my head. I could sometimes focus, like I’d come up with an idea to write or whatever, but it was allowed me to sort of forget the outside world and just focus on what was happening in the present moment.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:15] You know, it’s interesting as you’re describing that the other phrase that kept coming to my mind is flow. This this thing that people describe that’s been well researched also. And there’s a distinction that immediately came to mind because I was I’m thinking, well, what’s the difference between flow and mindfulness? And maybe this is just me, but my experience is that when I’m in a flow state, I have the experience of losing time. When I’m in a mindfulness state, I have the experience of time slowing down.

Karen Walrond: [00:38:41] Mhm. Interesting. I do talk about flow in this book, and there was something that said to me, what I thought about it was that by practicing mindfulness, it helps me enter into a state of flow for me. So like sometimes flow in a lot of ways for me doesn’t feel like it’s within my control, like it just sort of happens. Whereas I can focus on like I can be like, okay, I’m going to constantly keep bringing my attention back to this present moment. And so practicing mindfulness for me was sort of a portal to get into flow. But I love that losing track of time and time slowing down. I love that sort of the dichotomy of that. I hadn’t considered that, but I love that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:20] Yeah. And what you just said makes a lot of sense to me also, because you do have so much more control over the mindfulness aspect of it. It’s an intentional returning to the moment, to the experience. Whereas I agree, I mean, part of the definition that I described in Experiencing Flow is you really become absorbed in the activity of itself, and that’s why you lose a sense of self. So it’s almost like there’s no self to then become the observer for mindfulness anymore. You’re just in it.

Karen Walrond: [00:39:47] You’re just in it. It’s a great feeling.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:49] Yeah. Oh it’s amazing. But it’s also really hard to intentionally create.

Karen Walrond: [00:39:52] Yeah. For sure.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:53] Self-compassion.

Karen Walrond: [00:39:55] Yeah. So this one was actually going to be originally this was one of the ones that shifted as I was writing. It was going to be detachment of ego. Right. Like originally I was like, you got to be able to feel comfortable failing, right? What I kept coming up as I was doing, it was like, oh, this is actually about being compassionate to yourself when you fail. And this was the thing that I did for this, was returning to the piano practice, because I knew I was not going to be good at it. I hadn’t played the piano in 30 years. And so I knew my fingers were going to be doing weird things and that like, things were just not going to come as easily as they did. And I wanted to do something where I kept returning and being able to go, it’s fine, it’s okay. One of the women that I interviewed for this as a child, she was an avid roller skater. And she, you know, she grew up, she hadn’t roller skated very much. And then she had a breast cancer and she ended up having a double mastectomy. It took a lot of time to heal. And apparently I did not know this in the months where she had to have bed rest and was healing from her mastectomy, her body, her muscles atrophied. And when she was finally strong enough, she got the clearance from her doctor to return to the rink. And she went in knowing not only had she not done it for years, but also she was recovering from this, this really huge surgery. And so she had to practice this sort of self-compassion and go, I’m not going to push myself too hard. I’m going to go easy. And that’s a really lovely thing. Like, I think when you’re practicing intentional amateurism, the idea that you’re like, I’m not going to be perfect at this. I’m going to go easy. I’m going to fail. I think that’s really, really an important part of intentional amateurism.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:28] Yeah. And life. Right?

Karen Walrond: [00:41:31] Yeah. And life. Exactly right. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:34] It’s like the self-forgiveness, like actually saying, okay. Like, you know, I’m not who I was ten years ago or just things have changed and I can hold myself to the standard either of what I used to be able to do, or just some utopian standard of perfection where I think I should be able to perform at this level. Or I can own the fact that maybe things have changed in a way where that may actually no longer be accessible to me, at least not in the immediate or near future. And it’s almost like if you surrender that, you’re like, oh, now I actually have permission to just be in it.

Karen Walrond: [00:42:04] To just enjoy it. Yeah, it was really funny. I recently was talking and about this subject, and somebody in the audience said, You know, one of the things that I really love and I’ve loved all my life is basketball. But I’m in my 60s now. I’ve had some health problems, and I don’t want to go back to playing basketball, because I look at these young women in the WNBA and they’re so amazing. And I said, okay, but you do understand that you don’t have to be as good as the WNBA in order to do what you’re doing. Like, you can just go because dribbling a basketball is fun or shooting is fun, like that’s what you’re tapping into is just sort of that practice of what is the thing that’s really fun about without while also letting go of this idea that you have to be perfect in order to practice it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:46] I’m not good at that.

Karen Walrond: [00:42:48] It’s hard. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:49] Like letting go of that is a practice of mine. And I think repeatedly doing things that I know are going to be really hard and take a very long time to actually get good at is, on the one hand, frustrating. But on the other hand, it kind of forces you into that place of just grace and self-forgiveness and self-compassion or else, you know, it’s going to be a long road that’s not going to be enjoyable. And you just kind of like, let me just let that go because I just really want to enjoy this. Which brings us nicely to play also, which is one of the additional elements, the attributes here. Um, and this is one of our earlier questions where we really talked about the fact that we need this in our lives. And there’s research that shows play really matters. It’s not just for kids. Like it’s hugely important to our our physical and mental well-being.

Karen Walrond: [00:43:31] And that people who can be like axe murderers and serial killers, that they found that that probably happened because they didn’t have enough play in their life as children. Right. Like they it is definitely part of our developmental need, but also as an adult. And I just want I want to circle back to one thing. You know, you said that you’re not good at giving yourself grace and self-compassion, and yet you told a story about Metalsmithing where you were okay with going back and failing and going back. And I think that’s a testament to when you find the thing, it will be easier for you to practice that, that self-compassion. If it’s hard for you to do that, it’s probably not your thing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:07] Yeah, actually, I really appreciate that reflection. That helps.

Karen Walrond: [00:44:10] Yeah. So play you know we talked about that. It’s about losing sort of the sense of time losing yourself in the thing. Play generally doesn’t really have much of a purpose to it. Right. You’re just doing it for the fun of it. And yes, we all need more play in our lives. God knows we all need it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:25] Stretch zone. This is one attribute.

Karen Walrond: [00:44:27] Yeah. Yeah. So stretch zone was really interesting. Originally it was going to be comfort zone. Right. And one of the things that I read, which I thought was so interesting, was that, you know, we were all all constantly told you should get out of your comfort zone, you should get out of your comfort zone. And the thing about getting outside of your comfort zone is that you’re probably going to get hurt, right? Like like I forget who said it again, I’ve been quoting all kinds of people and forgetting the source, but the person who said that you should do something that terrifies you every once, every day, like, I think that’s madness. Like, why would I do something? The world is terrifying. Why would I do something like that? But the idea of starting where you’re comfortable and then stretching, being like, okay, I know I can do this. What would happen if I just stretched a little bit farther? Right. Just just enough that you’re within your comfort zone, but you’re actually stretching a little bit more? For me, this was when I did the surfing class. And for me, I love the ocean. I’m from the Caribbean.

Karen Walrond: [00:45:24] I grew up on the ocean. I love the ocean. So the ocean is not scary for me. For some people, people are like, there’s sharks. I’m never going to get in the ocean. Well, then you probably shouldn’t take a surfing class, right? But that wasn’t something. You know, I scuba dive. I’ve been around the ocean. I’m not a strong swimmer, but I’m comfortable with the ocean. So the idea of getting up on a wave and standing on a board and going like that was definitely out of my comfort zone. But it wasn’t for me. Bungee jumping or jumping out of a plane, which you’re never going to see me do because that to me is just terrifying. I would never do that. And so it’s really about how can I stretch myself to do something that maybe I don’t know if I can do it. I don’t know if I’m strong enough or brave enough and I want to try a little bit. So that’s part of the fun, right? Of doing an intention something, an intentional amateur thing where you’re just like, ah, what happens if I push myself just a little bit harder?

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:21] So it’s like stretching, but in a gentle way basically.

Karen Walrond: [00:46:25] Absolutely.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:25] And also I think that, you know, because one of my curiosities around this also is there do we can we reach a point where we’re stretching so much that what becomes a risk that makes sense, that helps open doors and lead to the feeling of growth becomes reckless. And I think you’re really you’re drawing the line well clear of that where it’s like, no, no, no. Like, let’s not even step to that place and just say, okay, so what would make me feel like I’m a little uncomfortable with this, but I don’t feel like there’s a meaningful risk here beyond my own sense of competence. Um.

Karen Walrond: [00:46:56] Exactly right. And for some people, skydiving is their thing. I hate heights, I’m terrified of planes or flying. Like, why would I jump out of a plane? That’s never going to be my thing. But for a long time, scuba diving was one of my avocations. It’s not anymore, but it was for. And there’s a lot of people who looked at me like, you are bananas. Why would you ever do that? But it doesn’t feel like an uncomfortable thing for me. And doing something that feels like life or death, that’s probably going a little bit too far. If it doesn’t feel like life or death, then maybe give it a try.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:28] And for you to like for somebody else. They may be like, bring it.

Karen Walrond: [00:47:31] Yeah, exactly. Exactly right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:33] I don’t know, when I was in my 20s, I drove out to a jump site with a friend to go up and actually, like, take my first jump out of a plane. And the plane was grounded because of high winds. And I took that as a sign from God that I shouldn’t be jumping out of planes. Never went back, never tried again.

Karen Walrond: [00:47:46] Good for you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:47] And I’m, I’m totally good with that decision. I’m 100%. I’m at peace with it.

Karen Walrond: [00:47:51] Absolutely right. And God bless the people like George W Bush or H.W. Bush. You want to jump at 75, 85, 95. Go for it. That is not my ministry. I am not going to be doing that.

Karen Walrond: [00:48:02] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:04] Connection is one of the attributes. I thought this was really interesting and this really speaks to, you know, the notion of, yes, we can be connected between just us and the activity that we’re pursuing, but also there’s a broader experience that sometimes happens when we do something in community.

Karen Walrond: [00:48:18] Yeah for sure. And this actually is a harder thing for me because I am naturally an introvert, right? And I noticed that, like most of the things that I was interested in doing, they’re really kind of messy things, right? Like there are things that I would do. Let’s take, for example, the craze for pickleball, right? Like everybody like pickleball is not something that I’m necessarily turned on to. But people love that idea of going and doing things with, you know, competing with somebody. And when I say competing, it’s competing for that moment, right? Like that I think is really, really healthy. What I did in this case was sailing. I went sailing with my husband and we were we took a sailing class together, and the feeling of the two of us learning something together And honestly, surfing was the same I did surfing with him as well. Like the idea of being able to cheer each other on and laugh when things didn’t quite go well without the feeling like either of us was going to put down the other person, right? Like it was sort of that’s a really, really lovely, healthy thing. And if you can practice amateurism where you’re connecting with family or friends or even strangers, but you’re all getting together to do something together and you have that, that, that lovely thing in common where you’re all doing it and that sort of collective effervescence that might happen. I think that’s I mean, we know there’s all kinds of research. Vivek Murthy, the former surgeon general, has written books about it like this. There’s something that is really, really healing and nurturing about doing things in community.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:51] Yeah, I so agree. I mean, this is, I think, why you also see so many craft based activities have circles or community like knitting circles, like crafting circles where people get together and commune around the shared pursuit of something, and they’re making it. They’re all working on their own projects, but it’s just doing it somehow, when you’re in the presence of others can be really beautiful, even when you’re an introvert, with both of us are. I’ll sometimes do this, and I’m not talking to anybody else, but there is something that just feels nourishing around, like knowing that, okay, so there are eight of us in this room doing this thing. We’re working on our own projects, and maybe it goes all the way back to that earlier part of the conversation where it’s like, now I’m in this micro community and we’re all part of a lineage, a heritage of people, and we’re all having this conversation without ever opening our mouths with each other through doing a shared pursuit of an activity, and also back in time and maybe serving as the people that one day future generations will reach back to and have the conversation with us.

Karen Walrond: [00:50:52] Absolutely. You know, and I’m sure you feel this at your studio, at your Metalsmithing studio. Same thing with me. Like I sort of reluctantly signed up to be a member of a pottery studio. Thinking like I’m such an introvert. I don’t know if I really like, maybe I should just get a wheel and do this at home. But what has happened has been this really lovely thing where we’re all focused on the same thing. We’re giving each other advice. We’re inspiring each other with our work. We don’t really even know what our backgrounds are, right? Like, these are a bunch of people that otherwise I may have never, ever included in my life. I would have just passed them on the street. Even though we’re all from these different backgrounds, we have this one thing in common and we all kind of want to see each other succeed. And that’s just such a lovely that’s a lovely place to be.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:36] Mm. So agree. And I think especially in, you know, in this moment in culture, in society where it seems like all we focus on is how we’re different and how we’re divided. Yeah. To have something where you just know that there’s a shared curiosity, a shared interest, a shared like you’re doing the same thing side by side. Even though you may be from totally different walks of life, it helps. It’s like an opening move, maybe in just seeing the humanity of somebody else.

Karen Walrond: [00:52:02] Yeah. And in fact, the book that I’m working on next is about communal compassion and how we take care of each other. And I think these sort of third space places where we can all gather together to do something together, is a really lovely way to sort of express compassion for each other. And we don’t we don’t even realize we’re doing it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:19] Yeah, I love that and so agree. That brings us to the seventh attribute. And we touch into this again earlier wonder and awe. And I guess one of my early questions is actually I’ve always wondered this. Is there a meaningful distinction between wonder and awe? How do you how do you think about them?

Karen Walrond: [00:52:33] You know, there is, and I apologize. I’m blanking on it right now. Brene Brown has written about it in her Atlas of the heart, about there’s a difference between the wonder that we feel where it’s sort of a curiosity, I think. I think, and then awe is more, um, like almost being overwhelmed by beauty or something like that. So it’s sort of both. There’s a curiosity part of it and the overwhelming of beauty. Me, I think that anytime we tap into either of those things. It actually helps us exercise an empathy muscle, right? Because when we start to think about ourselves not as these huge individuals that are better than everybody else, but actually an interconnected part of the world or of the universe, that it helps us remember that some of the petty differences that we see are just that, they’re just petty, and that we can start to remember that, you know, we’re all on this big blue marble hurtling through space together. And I think, again, it’s just one of those things that’s just good for us to remind, to remind ourselves of that. So, yeah, Wonder in law is probably one of my favorites of the things to tap into that feeling.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:41] I love that, and it resonates also to me. Wonder is often it’s like curiosity on steroids. And awe is something fundamental that I believed has now been shattered. And I have an invitation to reassemble the pieces in a new shape or form, so they kind of play together in a really interesting way. It’s like one leads to the other seven really, really interesting attributes. And I think the invitation here is really is there something that you can do in your life where you can let go of the fact that it has to have some sort of economic value, and you can just play, you can dabble, you can become that, that intentional amateur for no other reason than a feeling it gives you. And some of the feelings to look for are these seven things that you list out here. If somebody is listening to this or watching and they’re like, yeah, I would actually love to have something like this in my life where I can just turn to it on a regular basis and feel all the feelings that you’re describing, but I don’t even know where to start. What would you say to that person?

Karen Walrond: [00:54:44] Self-servingly I would just say, first of all, at the very back of the book of this book, the appendix, there’s like 250, I think things just to peruse and start thinking about. Maybe this would be something that would be fun. The other thing is actually, if you go to the website, I have a little quiz that you can take a little free quiz that will help you think like, what do I need more of in my life? Do I need more curiosity? And and that can lead you the right way? For me, what helped me pick the seven things that I did were often looking back into my childhood and thinking about what were some of the things that I really, really loved to do, or things that I’ve always kind of wished I could try and had never have? One thing that I think about now is, um, the aerial silks, you know, the sort of the circus, like that’s something that I’m like, for years I’ve been like, I really, really want to try to do that. I really want to. I just, I probably would look like a complete fool, but I really would like to do that and really sort of like make a list of those things that sort of keep coming up and then like schedule a class or start looking at you like YouTube University is a real thing, man. Like YouTube will teach you anything or just start playing with some of those ideas. Grab a friend. Write to take a class with you. That maybe would be interesting. That’s how I got into scuba. A friend of mine came to me and said, hey, I’m thinking of taking this class. Do you want to take it with me? And I was like, yeah, absolutely. And it became something that was quite a bit of a passion for a long time. So just really playing with the idea of what was it, the things that I’ve always thought about that’s really cool. I would love to see what would happen if I started doing that and then just taking the first step.

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:24] Yeah, I love that and I think I agree with you. I think YouTube is or like any online video, but obviously YouTube is the biggest. Like literally there’s nothing you can’t find on there anymore, which is probably both good and bad in a lot of different ways. But, um, it’s just a great tool also to kind of be like, oh, this thing popped into my mind. Let me see if there are a couple of videos about it. And like just watching the videos. Is there something, is there like a are you getting a visceral response like, oh, that’s actually kind of I’m interested. That’s it’d be cool to learn more about that. There are so many ways that we can See if there is like an interest in something without actually having to really invest time or money. We can do it from the comfort of our own couch. Yeah, excited to dive in, and I’m going to pay more attention in my own experiments. Now to those seven attributes. And when I do a no, fill them because I think they’re really valuable tells.

Karen Walrond: [00:57:15] Thank you very much. Yeah. It’s and again, you know, like that whole curiosity in yourself and your own evolution like these little tells, they’re just going to make you feel good. They’re just so good for you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:24] Yeah, that’s not a bad thing. It feels like a good place for us to come full circle. I have asked you this question in the past. It’s been a minute. So I’m going to ask you again in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up.

Karen Walrond: [00:57:38] To live a good life means, um, curating and creating a little bit of joy every single day.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:44] Hmm. Thank you.

Karen Walrond: [00:57:46] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:48] Hey, if you loved this episode, you’ll also love the conversation we had with James Victore about making your art and owning your point of view. You can find a link to that episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by Alejandro Ramirez and Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring, chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor. A seven-second favor. Share it with just one person. I mean, if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too. But just one person even. Then invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter. Because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life Project.