Have you ever felt the visceral impact of a poem that seemed to articulate your innermost thoughts and emotions with piercing clarity? In this soul-stirring conversation, renowned poet Sarah Kay invites us to explore the transformative capacity of poetry to dissolve the illusion of separateness and forge profound connections with our shared humanity.

Have you ever felt the visceral impact of a poem that seemed to articulate your innermost thoughts and emotions with piercing clarity? In this soul-stirring conversation, renowned poet Sarah Kay invites us to explore the transformative capacity of poetry to dissolve the illusion of separateness and forge profound connections with our shared humanity.

Sarah’s journey began at a tender age, instinctively turning to metaphor as a lifeline to navigate the depths of her experiences. From scribbling verses in childhood journals to finding her voice amid the raw energy of New York’s spoken word scene, her relationship with poetry has been a constant compass, an ever-evolving dance between the personal and the universal.

Prepare to be captivated as Sarah weaves tales of how a warm, inclusive community welcomed her poetic gifts from a young age, empowering her to share her truth fearlessly. Discover how she continues to create “doorways” that invite others to experience poetry in whichever form resonates most authentically – written, spoken, animated, or beyond.

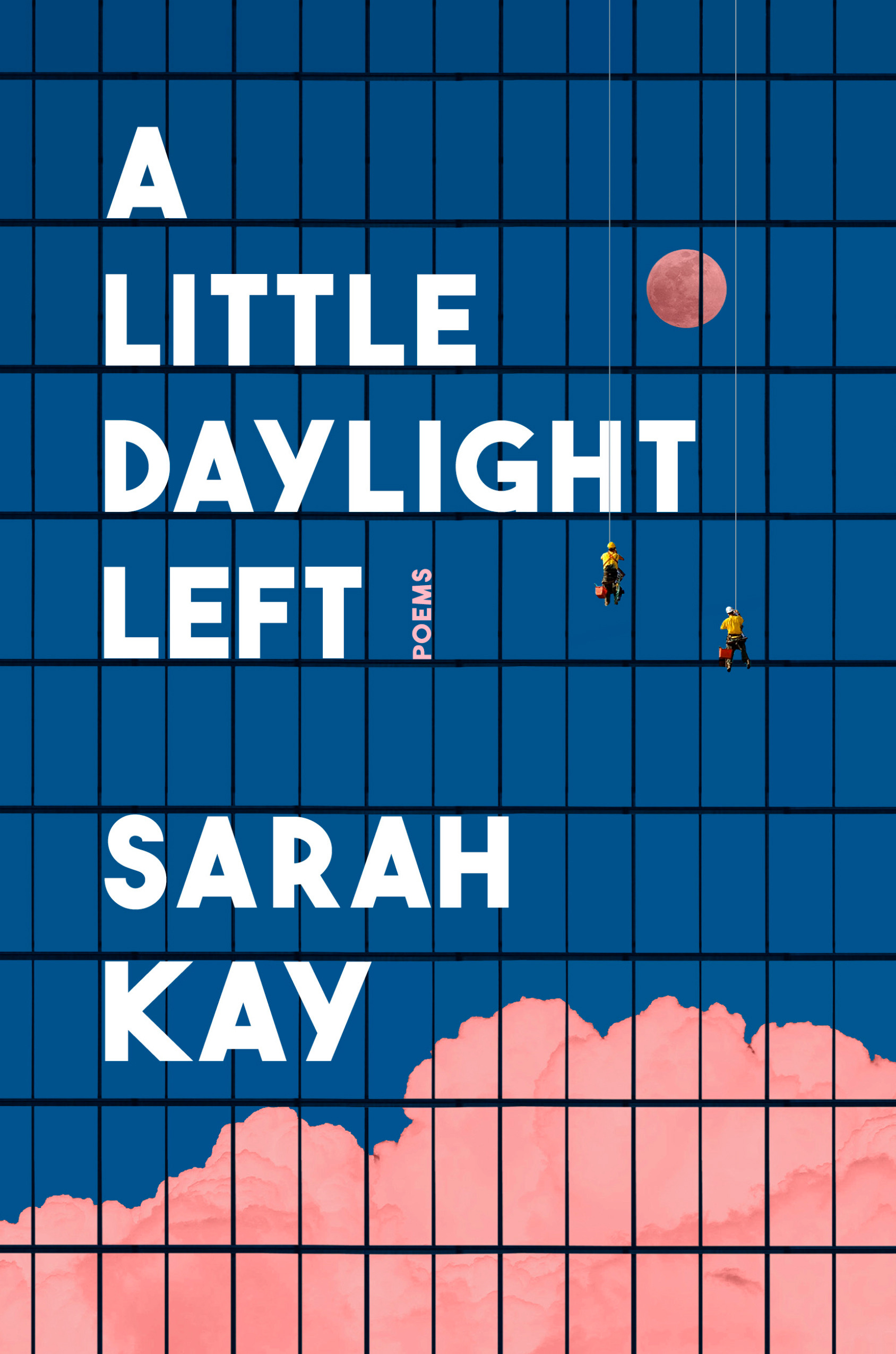

Within the pages of her latest collection, A Little Daylight Left: Poems, Sarah charts her profound relationship with poetry across the spectrum of life’s chapters, from grappling with violence and heartbreak to embracing love, aging, and mortality. Hers is an intimate memoir in verse, a testament to how the right words can illuminate our most searing moments with breathtaking wisdom and grace.

You can find Sarah at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Liz Gilbert about writing yourself letters from love.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Savannah Lauren

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:01] So what if I told you there was a secret language that could dissolve the walls, isolating you from your deepest emotions and the shared human experience? A profound yet ancient code for cracking open your soul and just excavating revelations that unite you with all of humanity’s beauty and pain and enduring truths. Well, that’s exactly what my guest today has tapped into and really mastered. Through a lifelong journey into the transformative power of poetry and the art of spoken word. Sarah Kay is a writer, performer, educator whose poetic genius has been leaving audiences spellbound since childhood with five critically acclaimed books to her name, including her newest collection, A Little Daylight Left Poems. Sarah’s relationship with this ancient art form is a tale like no other, from scribbling metaphor, rich verses and journals as a young girl to finding the courage to share her voice among New York City’s gritty spoken word scene. Her story really captivate you at every turn in our conversation, Sarah pulls back the curtain on how an embracing spoken word community really welcomed her raw, authentic expression from an almost shockingly young age. You’ll discover how the perfect words and images can just illuminate life’s most visceral moments from violence to heartbreak, aging, mortality, everything with sacred wisdom. But maybe most engaging is Sarah’s contagious passion for creating doorways through which anyone can experience poetry and spoken words. Medicine, whether written, whether spoken, whether animated or beyond, and will have the joy of hearing her actually read one of her deeply moving spoken word pieces. So excited to share this conversation with you. I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:50] I’m somebody who’s been a writer for the last couple of decades of my life. I have, on very rare occasion, dabbled in something remotely smacking of something that might resemble in the slightest bit poetry and felt weird, awkward, strange. But, um, captivated. Like when I read poetry or when I see spoken word that just, like, cracks me open in the best of ways. It’s there’s there’s so few other things that do that to me. Um, you have that capacity, and I’m kind of awed by people who have the ability to both craft the words and then share them in a way that moves people deeply. You’ve described your poetry in various terms as a lifeline and a lighthouse. Take me into this.

Sarah Kay: [00:02:39] Yeah. Um, first of all, thank you. That’s very kind words to say. I think that, uh, my relationship to poetry has shifted over my life. I started with poetry from a very, very young age. And when I was putting this book together. And I was trying to figure out what is the project of this book, specifically what poems belong in this book, I realized that the moments that I reach for poetry, the reasons that I reach for poetry, have changed and continue to change. And sometimes those moments are new, but the reaching is not. And the reaching is apparently one of the oldest parts of me. And I guess it’s a way that I navigate. It’s a way that my brain tries to make sense of things. Um, sometimes I use poem as a verb. So when I’m trying to understand something and I can’t figure it out and I just keep hitting my head against it. Sometimes I have to poem my way through it. And when I get to the end of the poem, I go, oh, that’s what was going on. Or sometimes I get to the end of the poem and I still don’t really understand what’s going on, but at least I have a new poem out of the situation. And so I think it started poems started as a way to help me make sense of the world, or some kind of sense of the world.

Sarah Kay: [00:04:28] And sometimes I still use poems for that. And I use poems for other things as well. I don’t know why I’m thinking of this very small story, but when I was a baby, my mom kept a journal and it was full of little notes that just for herself, it was her journal. But it was like her baby journal. And so she wrote down like little moments that struck her as notable. And all of the notes in the journal are written by her, except for one entry. And it’s in my handwriting. So I clearly was like, hey, I need this needs to be on record, apparently. And I think I must have been like, I don’t know, maybe 6 or 7. And the entry is a scene, like written, almost like a play. And it’s like me, mom, me mom, you know, like talking. I had, like, recorded a conversation my mother and I had, and it’s, like, misspelled. It’s, you know, but it was clearly very important to me that I, like, put this in the official record of my living that my mother was keeping. And the scene is I say something about like, I’m feeling weird. And my mother asks, are you anxious? And I said, no.

Sarah Kay: [00:05:56] There’s a woman weaving on a loom inside me. And sometimes the loom, the strings get tied in knots. And she was like, yeah, that’s anxious. But I think, um, like, it’s notable to me that before I was writing poetry, I was reaching for metaphor, not knowing what a metaphor was. Right? I was like the effort to try to explain myself by saying, what does this remind me of? Or what is this like? Is in the earliest part of me, before I even was trying to craft art out of it. Right. But the like reaching towards metaphor and using metaphor to help me make sense of my feelings and myself. And also notable that, like I wanted record of that, like I wanted someone, I wanted it to be clear that’s what I was doing. Yeah. Which is really wild and probably should be dug into with a therapist. But so that reaching for poetry, reaching for metaphor, my brain always going, what is this like? What does this remind me of? What else is like this? What else feels like this? I that is as early as I have memory. And so I guess, first and foremost, poetry is what I reached for when I was like trying to make sense of myself and my humanness.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:32] Yeah. I mean, without even knowing at that point it’s poetry. It’s just like there’s a way to describe it that’s emerging from me that I need to actually put language to. But that impulse that you described also to not just say, okay, I’m feeling this way, but I’m seeing my mom write these these things down. And like. This needs to be a part of that public record. Like the impulse to document and share, you know, because there are two different things. Like one is let me describe what like my internal landscape. Right. Let me see if I can put language to it. But then the other is the impulse to let me make it known to others. It’s a very different impulse and big time, unusual for almost anyone, but especially a kid that age.

Sarah Kay: [00:08:13] Yeah, I mean, I there’s a big turning point in my life and my relationship to poetry that happened when I was a teenager, and it’s sort of like a before and after, I think.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:24] Take me.

Sarah Kay: [00:08:25] Like before. When I was a kid, I loved language and I loved wordplay, and I loved poems, even when I didn’t really know what poems were. When I was in elementary school, my parents every day would pack me lunch and they would take turns. Day one was my mom. Day two is my dad. Day three was my mom, and each of them each day would write a little poem and fold it and put it in my lunchbox. And it’s funny now because it’s it sounds like an origin story, but they didn’t know that this wasn’t their plan, you know? Like, joke’s on them. They didn’t think this would happen. They were just finding opportunities to create little moments of joy and wonder and beauty for their kid, which is what they did across the board throughout my childhood. But they also inadvertently initiated my relationship to what a poem was and specifically, like, defined a poem as something that was a gift, something that was a surprise, but something that was also as dependable as clockwork, something that I understood to be a gesture of care and love from a person who loved me. Right. So, like, that’s what a poem was. And it was just for me, right? I opened my poem in my lunchbox for me.

Sarah Kay: [00:09:53] And so it was a solitary experience. It was one that I had internally. And that is what my relationship to poetry was for my childhood was. I wrote my little poems in my journal when I got old enough. I, you know, was not a performer. I did not do any acting. I did not do nothing on a stage. And then when I was about 13, 14, I got a letter in the mail that said, congratulations, you have been registered to compete in the New York City Teen Poetry Slam, and I had never heard of a poetry slam. I had never seen a poetry slam. I’m an elder millennial, so we didn’t have YouTube back then, so I couldn’t look up what that was. All I understood was that this was going to be a gathering of other teenagers who also liked poetry, and I was like, okay, that sounds cool. And I went to this event, and it was the first time that I witnessed poetry as a communal art form, and all of a sudden it was poetry in a room full of people who were excited to hear poetry, see poetry, share poetry with each other. The kids who had written poems were experimenting with a freedom to write about what they wanted to write about in the language that was authentic to how they actually communicate.

Sarah Kay: [00:11:22] And they were listening to each other and applauding each other and hyping each other up. And I was on the younger end. It was for all teenagers in New York City. So it was from 13 to 19, and I was in the 1314 age group. And it just blew my mind. I had never seen anything like it. And that shift from this is an art form that exists alone and only for you by yourself into this is a thing you can do with other people is, I think, what really moved my whole excitement around the art form and a sort of fun. A fun fact is that the event, the teen event was in. They had rented out this dive bar on the Lower East Side for the event. And on my way out, I saw these like bar flyers that said, you know, Thursday night poetry slam. And I was like, this event changed my life. I mean, I didn’t have those words, but I was like, this was the best thing that ever happened. I got to come back, I’m going to come back Thursday. And so I did, but I didn’t understand that 364 days a year. It was a dive bar.

Sarah Kay: [00:12:42] And so now I was a 14 year old in a dive bar being like, hello, I’m here for the poetry. And they were like, ah, okay, sit over there and don’t order any drinks. Right. And so I did, and I spent the four years of high school every week going to this dive bar sitting. I would sit underneath the bar, literally, because it was the best view up the aisle to the stage. I would sit under the bar and I would just watch poets. And so that era of my life, my poetry education, was kind of in the form of unofficial apprenticeship. I just watched a lot of poets share. And because I was lucky enough to grow up in New York City, a lot of people came through, and so I got to see really phenomenal poets of all different styles and all different ages and all different walks of life. And I learned so much in that space, obviously, about poetry, but also about life and community and healing and craft and, you know, so much more through the little window that I found in this dive bar. But I would say the big before and after was poetry, which is something I do by myself. To poetry can be something I do with others.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:17] Yeah. Did you during that time at all those that for your window, did you take the stage at all or was it was this more you sort of like watching and learning?

Sarah Kay: [00:14:25] Yeah. You know, the night was organized. They would have an open mic Mike and anyone could sign up for the open mic and then they would have a feature. Whoever was in town would do like a little feature that was usually an out of town poet visiting, and then they would have a poetry slam, which was a competition. And the first several times that I attended, all I did was sit and watch, sit and watch, sit and watch, sit and watch, sit and watch. And then finally one day they were like, hey, the open mics kind of quiet tonight. Like, we don’t have that many people signed up. Do you want to be on the open mic? And I was like, oh, well, uh, okay. Yeah, I could that, I could do that. And so I did, and it didn’t kill me and I loved it. And I also discovered that even in a room full of adults, they would still make room for me and listen to my 14 year old poem and take it as seriously as they took everybody else’s and clap when I was done. And so then I started to get brave enough, and I was on the open mic every week. And then one day they were like, hey, we actually need eight people for the slam and we’ve got seven, so we’re going to put you in the slam tonight. And I was like, what do you mean what? What does that mean? You know, I mean, I guess by that time I knew what it meant.

Sarah Kay: [00:15:51] I knew it meant you had to have three poems because there were three rounds. So just in case you made it to the final round, you needed three poems. And I think by that time I like had perhaps a grand total of three, three poems that I could do. And so then I started to be included in that. And so again, these adult poets just kept making room for me is how I always phrase it and how it felt. And it was a huge gift in my life, and also created kind of the work for me of the rest of my life, which is how can I make room for others. In poetry, the way people made room for me. And so a huge part of what I think about and what I work on and what I dream towards, is welcoming people into poetry, especially people who don’t realize that they are welcome there or have been made to feel unwelcome there in the past. Um, and also imagining like, what are the very many doors that people can enter into poetry, right? Like, I didn’t fall in love with poetry in a book. I fell in love with poetry in a dive bar. So if that’s how I met poetry, surely there are other weirder ways of meeting poetry. And so I like trying to think through what are different doors into poetry that people could hypothetically walk through.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:22] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. So powerful the way that you are just sort of seen at a really young age. Welcomed and not judged because, you know, like if one person had listened to you say something who you know, you saw as an authority or you respect and being like, nah, like, sorry, kid, you don’t have it. That would have been devastating, you know? And a lot of kids, you know, in their teens would have just said, you know, like slink away and said, like, not for me. Like, but you had this incredible experience of people just opening their arms and saying, no, keep coming. You know, keep doing this thing and then giving you opportunities. And then when you were doing it, saying more like, there’s something here. Um, I saw this a documentary at the local film festival a couple of weeks back about a songwriter named Diane Warren. Um, and when she was about 12 years old, similar to you, she got the bug in her head that that people could actually, she was looking at albums and realizing that the people writing the songs weren’t always the people performing the songs.

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:26] She’s like, oh, there’s this thing called songwriting. And back then, you know, Capital Records in LA used to have like a weekly thing where young songwriters can come and just offer, like their song of the week and 12 years old. She kind of, like, takes her old guitar and shows up and plays her song and, you know, a couple of weeks in and they’re like, no, no, no, not good, not right. But she keeps going. A couple weeks in, I guess it must have been a senior executive. She’s telling this story comes over and he’s like, look, this isn’t good. But you are there something like, keep showing up, you know, and I can’t tell you how many people I’ve spoken to over the years where there’s some version of this story where you’re young, there’s some ember burning inside of you, or you don’t even know it’s burning yet. You’re just there’s a curiosity and somebody or some group of people, some community is like, huh, interesting. Keep coming. And I feel like communities like that are getting lost a lot. For a lot of people, they just never exist in the first place.

Sarah Kay: [00:19:27] Yeah. I mean, I will say one thing that was helpful, probably without realizing it, is that the expectations around poetry are. I don’t know if the word is low, but it’s definitely not as set in concrete. You know, it’s a little more flexible, which is to say, I think when someone is like young and singing, right, there’s this societal projection, which is, okay, well, are they good enough to be a professional singer and have the singing be the thing they are known for, the thing they get paid for, the thing other people want from them, you know, like that’s the implied test put upon them even from a young age, you know. And so when someone’s like, no, you can’t or no, you’re not good enough or whatever. That’s what they’re suggesting, right? Is like, it’s cute that you like your little singing, but like, you don’t have what it takes to make it big. Right. But there’s not really a make it big in poetry. Or at least like we don’t understand there to be that. And so I think it would have been so strange for someone to be like, hey, kid, you expressing how you feel? Cut it out. You don’t have what it takes to keep doing that for the rest of your life. Like, you know, I think part of the piece that made it so beautiful is like, what were we there to do? We were there to gather. We were there to be together. We were there to share our unique human foibles and passions and fears and dreams in the form of using the language that we had cobbled together.

Sarah Kay: [00:21:23] And that was what we were there to do. And so there wasn’t I mean, yes, there were poetry slams, but poetry slams were very self-aware. At least the ones I was part of were very much like, this is a goofy thing. We’ve, you know, come up with to bring in an audience for poetry. But the competition part is, like, so goofy that it isn’t taken seriously in that regard. And so I think that had a lot to do with it is it’s like the adults who were gathered there were there to do what they saw me there to do. And I do think that an increasingly online world has brought certain lovely opportunities for people to be introduced to poetry in ways they wouldn’t have been able to before. For people to share poems with each other in ways that they haven’t been able to. For people to again find doorways in that weren’t there before. And I think an increasingly online world has made it so that the gathering aspect of sharing live art is harder to come by. And that is tough because I do think that it’s not replaceable. I do think that there is something that happens inside of us when we gather with intention, and when we gather with the desire to be together and share time and art and breath and, you know, all of these things that I got to experience as a young person. Um, and so that’s a big part of why I’m still doing it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:15] Yeah, it’s such an interesting observation to write that, you know, unlike music, where there is a juggernaut, there is an industry there. There are a limited number of spots and millions of people who are vying for those spots, and then gatekeepers and organizations and billions and billions of dollars. Like, like there is a path. Um, it’s brutally hard and very few make it. But there is this thing. So people are like, there are a lot of sharp elbows in that space. And what you’re describing is that there’s it’s interesting in that the fact that that doesn’t really exist.

Sarah Kay: [00:23:45] Well, I think it does exist. No, it definitely exists. Like poetry is also, you know, capital P poetry has like a lot of sharp corners. There’s unfortunately like a big scarcity understanding of poetry. There’s not that many jobs in academia. There’s not that many publications. There’s not a lot of grant money. Like all of that is true. Um, and certainly deciding to follow poetry as your career, or as the thing by which you hope to make money is perhaps not, uh, what I would recommend to anyone. But the good news is that writing poems is something you can do without other people’s permission, and sharing poems with each other is something we can do without a monetary exchange. And I think there is still ways that poetry can like there’s certainly fear and competition, you know, that exists around everything. Unfortunately, anything people are trying to make lives around. But also there are ways still to make poetry, share poetry, gather for poetry. You know, that is outside of those limitations and and that those sharp edges.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:16] Yeah. And I would imagine the vast majority of people who are in this, um, they’re not in the poetry industry, they’re in their in it for the experience of, of the creative experience, like the process of it, the gathering around it, the experiencing of it, you know?

Sarah Kay: [00:25:33] I hope so. And I also think, like a really amazing thing about poetry, too, maybe because of because the expectations are different and because the offerings are different and because we aren’t sure what it means to, quote unquote, make it big in the way that we are when it comes to songwriting or singing, for example. Because of that, there are so many ways to have poetry be part of your life, and those ways are all so valid and important. You know, I think the One of the greatest gifts of my life has been that I follow poetry. Poetry is my compass, and when I follow poetry, I get to meet people through poetry who have poetry in their lives in so many different ways. And I get to see different examples of how people orbit poetry, or how people exchange poetry, or how they cling to it, or how they, you know, share it. And there aren’t wrong ways of doing it. There are new ways of doing it and old ways of doing it. And I love getting to witness that and see all of those different ways. So by which I mean one of my favorite poets is someone who until very recently had published zero books And was a farmer, and would scribble their poems on the backs of scrap paper and envelopes, and wrote some of the most important poems to me in the world. And I know so many poets who work on 9 to 5 in a cubicle and also write beautiful poetry. And I know people who, you know, have this invisible thread that runs through our lives without it being their job or without it being without being part of the capital. B poetry capital I industry.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:45] Yeah. I mean, it is interesting, right? The um, when I think about, you know, obviously like everyone knows a lot of the big name poets, especially around these days, and we’ve seen pieces pop off like both visual pieces, spoken word pieces and also written pieces, you know, like, and on in the online world, you know the potential for poetry, to, quote, go viral. You know, is something that didn’t exist. Not too long ago. And it’s sometimes I wonder about the difference between okay, so you know. So okay. So Maggie Smith writes good Bones that wasn’t a spoken word piece, but it goes out into the universe and just boom, explosive response. And people are sharing, sharing sharing sharing sharing. So they’re responding to something in the actual written word itself, right? The cadence, the rhythm, the tone, the story, like the field of vibe of it, is entirely internal to them. Nobody is actually performing this to them, right? And yet there’s something that is still so stunningly powerful about it and a very different experience from, you know, had Maggie or somebody else penned that, and then there’d be a video of a really powerful performance of that same thing, very different thing. Totally. You know, and I would imagine two different people, one would respond really powerfully just to the written word. Watch the video and be like, huh? And the other would watch a video and be bowled over by it. But if all they saw was text, they’d be like, oh, cool. It’s it’s so interesting how as individuals, the exact same words, depending on how they’re shared, can land so profoundly differently.

Sarah Kay: [00:29:20] Well, that’s that’s what I mean when I talk about doors into poetry. So I’m always thinking like, okay, are you the kind of person who would pick up a book with a beautiful cover? If so, great news. I’ve got one for you. And are you the type of person who would never pick up a poetry book, but you might listen to an audiobook? I’ve got one of those too. If you are like, no audiobook, but I would watch a three minute YouTube video of a live performance. Got plenty of those. If you’re like, I’m not interested in a live performance, I would rather read the text, but I am nervous about the quote unquote right way to read poetry. And I’ve never done that before. And I need someone to show me how to do it. I got a chance to help curate this series, where we asked poets and people who love poetry to read a poem they love, and the visual is the text on the page and the audio is this person reading the poem? So you get a chance to see how someone would read it, and it kind of shows you. It guides you through that. But the visual is the text, right? And if that sounds not for you, maybe you’d be interested in a short animation. I’ve curated videos where it’s a collaboration between an animator and a poet, and if you’re not into animation, maybe you’d be into, you know. So I’m always thinking about the person who doesn’t realize that there is a place for them in the House of poetry, And there’s no wrong door to enter through.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:02] But there’s a place for poetry in the house of them.

Sarah Kay: [00:31:05] Yeah? Yeah. Beautiful. Yeah, exactly. Um, and so I, I agree. Like, there’s people for whom they would be deeply moved by a poem in a certain form and in a different form. It wouldn’t be for them. And that just means, you know, they need to meet the poem that is right for them in the moment. That is right for them. But we can certainly try to help by offering a lot of options.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:32] Yeah. No, that makes total sense. I mean, you know, example of you, you know, standing before Ted sharing a long form poem, you know, and this is an unusual audience, I would say for, for, you know, so you get there. And this is not your typical audience. These aren’t people who’ve raised their hand and saying, I’m showing up here exclusively to hear a poet stand before me and actually do a spoken word piece. These are people there. These are movers and shakers from around the world. It’s a large audience, and they gather to hear a lot of intellectual talks and big ideas and this and this. When you step up on a stage like that and do a deeply personal piece, what’s that like for you?

Sarah Kay: [00:32:14] Well, I have spent most of my life stepping into different kinds of rooms to share poems. Those rooms include dive bars. They also include middle school gymnasiums.

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:37] Maybe the toughest audience listens.

Sarah Kay: [00:32:41] They include weird conference, ballroom business. Multimedia room at the Hilton. Then they include, you know, someone’s living room, a backyard. I’ve been in so many different spaces because I really believe that poetry can exist in all those spaces. And I really do believe that sometimes people don’t know that poetry is available to them. And I like being part of the journey and sometimes being people’s gateway drug to more poetry. So in some ways, stepping onto a stage like Ted is the same puzzle that it always is, which is who is here. What are they expecting and what am I here to communicate to them? And that is what my brain is doing anytime I’m on stage. Whether it’s a room full of middle schoolers or otherwise. And sometimes you’re right. Sometimes I’m stepping in front of an audience of people who came here to hear poetry and they, you know, bought a ticket to see a show of me doing poems. And that is a very different set of expectations and context, as opposed to people who don’t even know that poetry is about to happen. And so sometimes I have to walk people or don’t have to, but I like to walk people in to the poem in a way that allows them to feel comfortable before they realize that a poem is happening.

Sarah Kay: [00:34:45] Sometimes I like to start and go, you know, Energetically like, okay, here comes a poem ready poem. But actually, more often than not, I don’t do that. More often than not, we’re just talking. Here I am, I’m Sarahh, we’re having a conversation. I’m telling you about some things. I’m telling you. I’m starting to tell you a little story. And then I’m already halfway into a poem when people are like, now hold on a second. Is a poem what’s happening right now? Yeah, exactly. And I think that it is an effort to sort of, um, demystify poetry sometimes or just to when people have their guard up around poetry, um, to not give them a chance to, like, raise that guard before they get an opportunity to maybe just feel and be. But all of that, all of those little sort of choices and strategies are all kind of part of the same Series of questions, which is, you know who’s here? Where are they at? And how do I reach them?

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:55] Yeah. I feel like in in a certain way, um, spoken word poetry can be pretty subversive, especially depending on the room that you’re in and the expectations. You know, but not subversive in a bad way, but subversive in that. It’s almost like there’s, um, like in a Trojan horse way in that, you know, you can embed some really powerful, some really hard, some really tough, some vulnerable issues and thoughts and stories and feelings and a poem. And if you just came out on stage and you said, okay, so we’re going to talk about this, you know, here’s my presentation, here are my slides. And like here’s the data. You know, people would immediately recoil and not be open to it. But if you actually do it in a really artful way in spoken word. You know, all those people that would have been like leaning back or heading towards the door. You find them leaning in and feeling and their minds opening to it, and it’s like they may not even realize what’s just happened until it’s already happened. I’ve had that happen to me, and I’ve seen that happen in rooms where everyone’s like, whoa, um, did not see that coming. Might not have been up for it had I known. But now that I’ve experienced it, just just. Wow.

Sarah Kay: [00:37:19] Yeah. I mean, I think a lot about just how many different vessels and different shaped vessels there are for wisdom and truth and beauty. And there are certain vessels that we societally, let’s say, are more familiar with or that we consider more authoritative. For different purposes. And some we should. But I think a lot of times the vessel, the form of poem is not is just one that people aren’t as familiar with largely. And but it is a meaningful vessel and an ancient vessel. And we have humans have passed wisdom and beauty and truth and humanity to each other in the vessels of poetry and continue to. And so I think people having their eyes opened to that vessel as a possible vessel in their lives helps tremendously, Even just knowing that that’s possible.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:44] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. You mentioned earlier that from the earliest days, you know, like you’ve been even before you knew what a metaphor was, you’ve been looking for metaphor to try and describe your, your, your inner world. How can metaphors, which are such an essential part of poetry, help us when we’re experiencing moments of shattering, of awe, of, you know, like decompensation, whatever words you want to use. You know, so often we’re saying we’re told to just go directly into it. Metaphors is is a really interesting tool for those same experiences. And take me into your, your your thoughts on this.

Sarah Kay: [00:39:33] Oh man. We could talk for a whole hour. Just on on metaphors. I mean, everything runs on metaphor, the metaphors we use to describe the world to each other and to ourselves define how we interact with the world and ourselves. Right. The poet Ocean Vuong.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:56] Yeah, we’ve had him on the podcast.

Sarah Kay: [00:39:57] Just stunning and speaks a lot about the ways in which, for example, success is often framed with language of war and violence. Right. Oh, you killed that. Oh. You slayed. You know, like that. You know, we’re going to nail them. We’re going to. We’re going to destroy them. Right. And that’s not without impact. To have the metaphor of war and dominance be what we reach for when we mean Triumph. Even people who think they don’t want anything to do with poetry, that poetry isn’t for them. They don’t get it. They don’t like it. Even those people still rely on metaphors to make sense of themselves and each other. So much of my experience of therapy is searching for the right metaphors and analogies. You know, I gave the example of there’s a woman weaving inside me and she just made a knot. That was me trying at age seven. But I’m still doing that. I’m still trying to find metaphors to understand how I interact with, you know, others, and I think other people do, too. And even people who think they don’t like poetry, don’t want poetry, still often reach out to me, for example, or others. In very specific moments when they need a poem.

Sarah Kay: [00:41:47] Moments like my sister’s getting married and I want to read a poem at the wedding. My father died and I want to read a poem at the funeral. I have fallen in love, and my whole world has been turned upside down. And I can’t make sense of it. And I don’t know what to do. And there’s a reason why poetry is reached for in those moments. And that’s because a lot of times, poetry offers language for what we previously thought was unthinkable. And I think when people have the instinct to say I am feeling something good or bad or complicated or wrought and I feel alone in it, surely nobody has ever felt as good or bad or wrought as I feel in this moment. Discovering that not only have other people felt this way, but they have also done the work of searching for language to help share it and share what it feels like to me. There’s almost no greater feeling than stumbling upon a poem in the exact moment you need it and going, oh my God, they found language for the thing that I didn’t even know I needed language for until I read their poem. And because that’s such a powerful moment that I have had.

Sarah Kay: [00:43:35] I also love trying to make that moment happen for other people. You know, when people say like, oh, my sister’s getting married and I need a poem. Do you have any recommendations? You better believe. Um, my sleeves are rolled up like I’m ready. That’s that’s. But I like it. Even I like it in even less obvious. You know, wedding time feels like that’s when everyone reaches for a poem. But there is a very brief period of time where I got to do this, this really sweet project for the Paris Review Online, where myself and Akbar and Claire Schwartz to other wonderful poets and friends, we co-authored this sort of faux advice column. We called it poetry. And people could write in with their very specific heart ache, and we would prescribe a poem for their troubles. And, you know, tongue in cheek, obviously, but, uh, but the most delightful was the most specific of request. Right? Like, I submitted for a job that I’m not going to get, and I already know, but I have to send the application anyway. Do you have a poem for this? And being able to go? Yes, I, I do.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:53] Which. Which one? There’s somebody. Yeah.

Sarah Kay: [00:44:56] Right, right. But I think that that is talking or like that’s touching on to be human is to experience so much and to have the sinking suspicion that you’re the only one that’s ever felt it. And if we’re lucky to also find art or conversation that shows us we are not the only ones. And we share this actually, and it is communal. And look at the way someone else has found language to help them navigate it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:35] Yeah. I mean, it’s like, you know, the way you’re describing it. Poems don’t resolve anything. They don’t provide answers to burning questions or solutions to complex problems. What they do is just dissolve the illusion of separateness, you know, which is maybe the greatest pain we suffer. So in doing so. Like, maybe that’s enough.

Sarah Kay: [00:45:56] I have seen people use poems and need poems for so many different things. And certainly companionship or. Feeling part of something. Feeling connected to something is a Particularly powerful aspect of poetry for me at least.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:32] And I think it’s something so many people don’t feel these days, increasingly. Um, I do want to talk a bit about the new collection. A little daylight left if I have this right. Is this the first collection you release in about a decade now?

Sarah Kay: [00:46:50] That is correct, yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:51] So. And I would imagine that during that entire decade, you’re still writing.

Sarah Kay: [00:46:55] Ah, yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:56] Right. So I can’t even imagine the task of then looking back over a decade and saying, okay, what goes into like, this book? Because the volume of stuff that must have been left out of it has got to be exponentially larger. How do you even wrap your head around saying, okay, ten years worth of work? I need to actually, I’m putting together one book, um, one collection. How do you wrap your head around what actually goes into crafting that.

Sarah Kay: [00:47:26] I do think that because I love poetry in so many forms. I also don’t create a hierarchy in my head for the form. Which is to say, sometimes I write a poem, and the purpose of writing that poem was for me to write it, and I put it in a drawer. And that’s all that that poem needed to do. And sometimes I write a poem, and I share it with a room full of people, and that feels great. And that is what that poem was for. Sometimes I let someone or ask someone to put a video of it out there, and then people have access to the video. Sometimes I see if I can get the text published online. And so I didn’t feel, for example, that the poems that ended up in the book were somehow like that. The book itself made the poems more important, or more special or more real than the other poems. And that freed me to say, okay, so I’m going to make a book. And what is the most exciting version of a book to me? And to me, my most excitement around any piece of art is when there is something about the form that is justified in the art. So, for example, the worst feeling is when I’m reading a book and I’m like, oh, this book is so fun, but it’s going to make a better movie and I can tell are going to make it into a movie, you know? A great feeling is when I’m reading a book and I’m like, oh, this had to be a book.

Sarah Kay: [00:49:21] This isn’t going to work in any other form than the one I’m encountering. And one of the things I do when I’m performing poetry is I try to make choices in performance that allow the people in the room to have the feeling somewhere inside of them, or the the small experience of, ooh, I really had to be here. I wouldn’t have been able to see that wink or that gesture, or hear her tone of voice when she said that one line, even if they’re not thinking those thoughts consciously, that there’s something about the performance that feels like this is the form that I. That I needed to see this poem in. So to make a book, I thought, I want someone reading the book to go, ooh, I really had to read this book. This book needed to be in this form, in this order. I wanted to think about the way your eye moves on the page, and how to pace both a poem and also an arc inside a book. And so I really thought about the experience of this one book, and what poems would allow me to create the best version of this form, which I know sounds like maybe so granular, but that’s what I was doing. And so I realized pretty early with my amazing editor, Maya millet, that I have so many poems that kind of chart the evolution of my reaching for poetry, which is a little meta, but is the case.

Sarah Kay: [00:51:14] So I have poems that show me using poetry to help me process. Growing out of childhood and in my case also that coinciding with violence, entering my life and consciousness, interpersonal violence, gendered violence. And so the first section of the book is showing how this character reaches for poems to help her process childhood, leaving childhood and violence. The second section of this book shows how I reached for poetry to process falling in love and being in love. And spoiler alert, heartbreak. And the third section shows how I continue to use poetry to reach for poetry, to help me process aging and mortality. And. The questions I’m asking now. And so once I saw that potential pattern and that there were poems that showed that it showed a life of grappling with what poems can and can’t do and what poems are for or aren’t for. When poetry is helpful, when poetry is not helpful to me, when it feels like a gift. When it feels like a burden. When it feels like a friend. When it feels like a compass. And so the book ended up being more memoir rustic than I intended or imagined it when I started. But I think I really wanted there to be a reward for a person who reads the book from beginning to end. I wanted there to be an arc. I wanted there to be a story. I wanted us to explore something together. Um, and that’s what sort of earned each poem its place in this book.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:31] Hmm. Now. And the arc is definitely apparent, you know, as you move through it. Um, it does feel. It’s interesting you use the word memoir because it’s kind of like as I was like, oh, this actually feels like there is that there’s this narrative that sort of like moves through, weaves through all the different poems and different seasons of life and experience. Um, could I invite you to potentially read something for us? I’m thinking about something from that part three, actually. Sure. I have I literally have like, digitally dog eared, like literally almost every poem in this book. It’s like so nice. This is I’ll ask you to read this or this or this. And I’m like, okay, that’s all of them. We can’t do that. So maybe my curiosity is what feels most alive in you right now that you’d be interested in reading.

Sarah Kay: [00:54:17] Well, we’ve been talking so much about the right way to beat poetry and how there’s so many doors that you can enter through, and how excited I am for people to enter through any door. Um, and so there’s a poem pretty late in this book, very close to the end, which is me really thinking about the person holding this book and my desire to directly address them. And there’s a common, uh, you know, literary trope of like, dear reader. And, um, so I thought I’d write a poem. Um, in that spirit, uh, which is called reader, dear, maybe where you are. It is nighttime, or maybe it is day. Maybe someone is reading this to you the way any dear one of mine would warn you that going into a bookstore with me entails being read to like. The poetry section is the dressing room I’ve parked myself outside of where I keep making you try on poems until we find one that’s a good fit. Or maybe you’re reading to yourself unaccompanied, maybe out loud, or maybe in silence. Maybe in a special accent you have for poetry that nobody else can hear. Maybe you haven’t committed yet. Maybe you are skimming through pages and trying to decide whether you can justify another book, especially one without a twist ending.

Sarah Kay: [00:56:03] Maybe you are looking for a gift for someone and you heard somewhere a book of poems is a good offering. One time someone broke into my rental car and opened a box of my books and took the books out, but left them all behind. And sometimes I imagine they stopped mid burglary and flipped through a couple poems before deciding. Not for me. So maybe that’s what’s going on right now. Maybe you have broken into my rental car and are standing there thinking, not again. Maybe you’re heartbroken and you’re looking for someone else to find language for what doesn’t feel language able. Maybe I’ve been there. Maybe you’ve borrowed this. Maybe somebody lent it to you. Maybe the library or a friend. Maybe you stole it. Maybe on purpose. Or maybe the way I borrowed Jeff McDaniel’s poetry book from the Urban Word Library once, when I was 14 and just forgot and never gave it back. Because sometimes that is also how burglary works. So slow and ordinary and unnoticed by even you who are doing the stealing. And then boom, years have gone by and you’re holding something that isn’t yours.

Sarah Kay: [00:57:10] And somewhere there’s a hole that you caused in the fabric of everything. Maybe you’re sorry, maybe you’re guilty. Maybe you’re as disenchanted as I am by the kingdom of ownership and are ready to disavow it entirely, to embark somewhere. The entire premise is absurd. The only rule my parents had when I was growing up was we share in this family, which they used to scold me if I was withholding something my brother wanted, but somewhere along the way it morphed into a guideline. If I have something, then I have something to share and that’s it, I guess. Half my sandwich and also my couch. Also my afternoon. Also. What happened, what I’ve learned, what makes me laugh? What made me think of you. What I think the poem of means. The metaphors I’m using to explain things to myself. What I can’t figure out, what I don’t want people to know about me, and what I don’t want to know about me. And it isn’t a superpower. It isn’t a curse. It isn’t a legacy. It isn’t a trap. It is what it is, and it is what I’ve got. And you can’t steal it. Because right about now is when it becomes yours too.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:30] Beautiful. Thank you. Thank you. That’s a good place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up.

Sarah Kay: [00:58:43] To live a good life? Make room for yourself and make room for each other.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:51] Thank you. Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode, safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Liz Gilbert about writing yourself letters from love. You’ll find a link to Liz’s episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help By, Alejandro Ramirez, and Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring. Chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor. A seven-second favor. Share it with just one person. I mean, if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too. But just one person, even then, invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter. Because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time. I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.