Money. Some view it as a dirty word. Others live their entire lives in pursuit of it. There is so much mythology and misinformation about what it really takes to build life-changing levels of wealth. Even if we find a way to be well-informed, and are fortunate to be in a position to be thinking about building wealth, so many are still left to deal with the often triggering family and cultural patterns, assumptions and values we’ve adopted, and been pummeled by, around money.

Money. Some view it as a dirty word. Others live their entire lives in pursuit of it. There is so much mythology and misinformation about what it really takes to build life-changing levels of wealth. Even if we find a way to be well-informed, and are fortunate to be in a position to be thinking about building wealth, so many are still left to deal with the often triggering family and cultural patterns, assumptions and values we’ve adopted, and been pummeled by, around money.

What if you could reshape your entire relationship with money?

I’m willing to bet that at some point you’ve felt confused, overwhelmed, or just plain frustrated when it comes to personal finance. It’s not easy to navigate, especially when so many supposed “experts” seem to be speaking a different language.

But what if you had a guide, a mentor who could decode it all for you in simple, practical steps? Someone to help you adopt a realistic, yet affluence-friendly mindset and stop just getting by paycheck-to-paycheck?

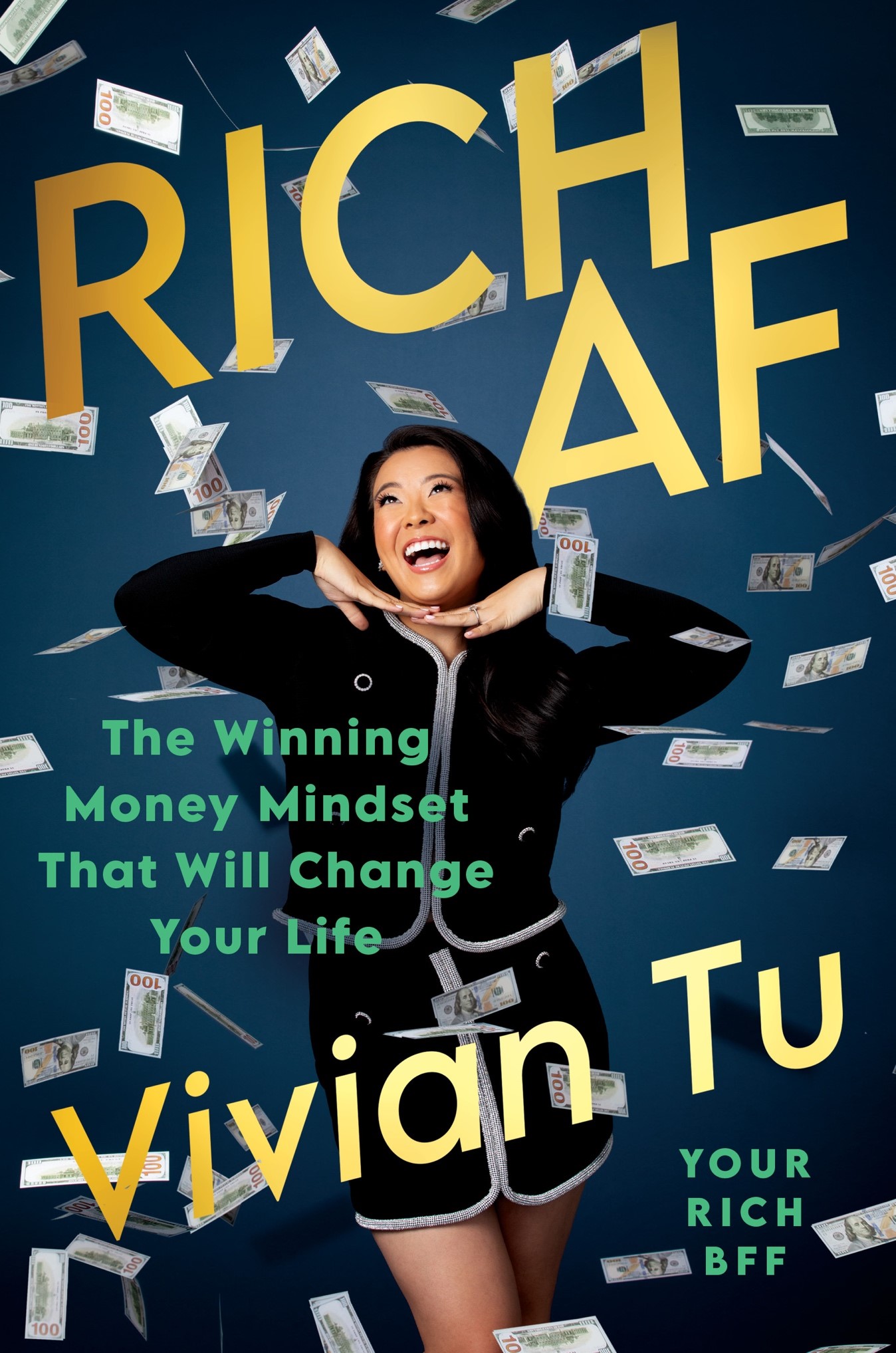

My guest today, Vivian Tu, is on a mission to do just that. She’s a former Wall Street trader turned personal finance phenom, educator, and now author of the new book, Rich AF: The Winning Money Mindset That Will Change Your Life.

After burning out in the toxic environment of high finance, Vivian found a new purpose: making financial literacy accessible – after she realized there was a huge unmet need for judgment-free financial advice. Especially for people who’ve traditionally been excluded from a level of financial intel that can be lifechanging. She started creating viral TikTok videos packed with no-BS money advice. Now, with millions of loyal followers, she’s become a leading voice empowering everyday people to get smart about money and achieve financial freedom.

In our conversation, we dive into the assumptions, misinformation and missteps that so often become the dominant tropes in personal finance. Then, Vivian shares specific insights, strategies and tips designed to help equip you with tools and knowledge to understand finances and build your own generation-changing wealth strategy, no matter where you are in life. We explore ways to maximize earnings, how to negotiate your true worth at work, overcome investing fears, adopting simple, effective habits to grow wealth, and then tap this resource not just for your own security and wellbeing, but also to make the world a better place.

You can find Vivian at: Website | Instagram

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Patrice Washington about wealth and purpose.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Heidi Gutman

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Vivian Tu: [00:00:00] Money is being able to leave a bad boss. Money is being able to leave a bad relationship. Money is being able to leave a bad apartment. It gives you the power and agency to live the life you want to live without fear, because it gives you choices. And so I think it’s so important to encourage people to want money, to want wealth and richness in their life because it gets them out of bad situations and lets them choose exactly how they’re going to live and what a happily ever after means to them. You just need to start, because time in the market beats timing the market or picking the perfect investment every single time.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:37] Money. Some view it as a bit of a dirty word. Others live their entire lives in pursuit of that. There is so much mythology and misinformation about what it really takes to build life-changing levels of wealth. Even if we find a way to be well informed and are fortunate to be in a position to be thinking about building wealth, so many are still left to deal with the often triggering family and cultural patterns, the assumptions and values that we have adopted, often unconsciously and then been pummeled by around money. What if you could reshape your entire relationship with money? I’m willing to bet that at some point you felt confused, or overwhelmed, or just plain frustrated. When it comes to personal finance, it’s not easy to navigate, especially when so many supposed experts seem to be speaking completely different languages. But what if you had a guide, a mentor who could decode it all for you in simple, practical steps? Someone to really help you adopt a realistic yet quote, affluence-friendly mindset and stop just getting by paycheck to paycheck. My guest today, Vivian Tu, is on a mission to do just that. She’s a former Wall Street trader turned personal finance phenom, educator, and now author of the new book Rich AF The Winning Money Mindset That Will Change Your Life. So after burning out in the toxic environment of high finance, which we dive into, Vivian found a new purpose that really took her by surprise, making financial literacy accessible after she realized there was just this huge unmet need for judgment-free, real-world, authentic and actionable financial advice, especially for people who’ve traditionally been excluded from a level of financial Intel that can be life-changing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:17] So she started creating these viral TikTok videos, just packed with straightforward money advice. And now, with millions of loyal followers, she has become a leading voice in empowering everyday folks to get smart about money and achieve financial freedom. In our conversation, we dive into the assumptions, the misinformation, the missteps that so often become the dominant tropes in personal finance. And then Vivian shares specific insights, strategies, and tips designed to help equip you with tools and knowledge to better understand finances and money and build your own generation. Changing Wealth strategy. No matter where you are in your life cycle, we explore ways to maximize earnings, how to negotiate your true worth at work and yes, things like that are a part of personal finance. Things like overcoming investing fears, adopting simple, effective habits to grow wealth, and then tap this resource not just for your own security and well-being, but also to help make the world a better place to be. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:27] So it’s really interesting. You literally start out your new book with the line, “I hate to be the one to tell you this, but the American dream is dead.” Take me there.

Vivian Tu: [00:03:39] Yeah. I mean, I think when I think about my parents’ generation, right? It was a blueprint that you were supposed to follow. You could be a decent student, go to college, get a degree, get a desk job. You could be the sole breadwinner in your house. You could live an amazing middle-class life, go on vacation to Florida or Disney World or whatever. Twice a year you would go on two vacations. You would be able to afford a home. Eventually you would build your wealth along with the real estate market, which only goes one way, frankly, and you would live your happily ever after. And since then, I feel like my I’m a millennial, so my generation and the generation after mine, Gen Z and even Gen Alpha, now we’re looking around and we’re like, hey, I don’t know if this playbook works anymore because we did everything we were told we were good students. We did go get those degrees, and now we have a student debt crisis. There are trillions of dollars of student loan debt that needs to be paid back. And a lot of students ended up getting degrees that didn’t pay back, that didn’t have the ROI they were looking for. Not to mention, wages have stagnated. The cost of housing has in many cases, depending on where you live, somewhere between 3-10x and life just doesn’t necessarily look like it did back in the good old days. And so I think it’s really important for us to address that. The way to wealth, the way to financial security and stability is not the same as it was decades ago.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:21] Yeah. I mean, it’s interesting, right? Because I think we work on a set of assumptions about the way the world is when it comes to opportunity and potentially wealth-building. Just if we do a certain thing, if we show up a certain way that X, Y, and Z will happen, you know, and we trust in that. And, and I feel like what you’re describing is right. You know, that kind of worked for a couple of generations. But the truth is also, I think when you look underneath that, it also kind of worked for certain people. Correct. And it didn’t work for other people, you know. So what you’re describing as that American dream, it was never really the American dream that was inclusive in any meaningful way. This was like for a certain group of people who showed up in a certain place in a certain way. Yes. And now I think what you’re describing is now that sort of, you know, sense of anointing has gone away across the board. Yeah. And people are grappling with this fact, like, okay, so what do we do now? But it’s interesting also because you, you came out of a family in Baltimore, um, from what I understand, your folks were, um, first-generation immigrants.

Vivian Tu: [00:06:27] I’m the First gen. My parents were the actual ones who immigrated. Yeah, on. My dad got a J-1 visa, so he was on a student visa. You know, both of my parents are educated. I’m very lucky in that way. My parents both have college degrees from China, and my dad actually has a master’s degree that he got at Towson University in Maryland. And so they’re nerds. I’m lucky to be the daughter of two big nerds. And because of that, they were able to gain entry to this country in a way that, you know, many immigrants don’t necessarily get that opportunity. Another common visa for countries like India and China is the H-1b visa, where essentially the US government hand-picked engineers, doctors, lawyers, computer scientists, people who were highly educated had a very refined set of technical skills that could then essentially come to the US and make the country better. So when people make the joke or trope of why is everybody’s doctor Asian? Or why are so many engineers Asian? It’s like, what do you mean? Like we literally have immigration policies that made it so. So to your point, I think the American dream was only the American dream for what many people visualize as American when they close their eyes. You’re looking at a white heterosexual family, likely moderate, upper middle class, you know, the white picket fence house. It didn’t work for people of color. It didn’t work for women. It didn’t work for the LGBTQ community. It certainly didn’t work for people who were immigrants or grew up low-income. And now that essentially the middle class is being squeezed, those same people who believed in that American dream are now looking back and saying, I don’t know if this ever really worked for everyone. How can we actually make this fair, and how can we make it just and how can we move forward so that all of us can have that financial equity that we’re all so desperately looking for?

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:27] Yeah, I feel like we really are in that moment right now. I mean, I’m curious also, as a kid then growing up in the household that you just described, what were the conversations around money?

Vivian Tu: [00:08:35] Oh my gosh, my parents are very frugal. Let me put that out there. They have been frugal for as long as I can remember. They’re still frugal today, and their financial situation looks very different now than it did when I was younger. Growing up on evenings, my mom would take safety scissors and I would get the pair of safety scissors, and she would get the regular pair of scissors, and we would sit while we were watching TV or like hanging out for the evening after dinner, and we would clip coupons. And she was like, Vivian, you see, like anything with this, like dotted black line with the scissors around it, like you’re cutting that. And then she would review the coupons I had cut and put them in her little coupon holder. And there was a huge emphasis placed on saving, budgeting. Um, there’s a Chinese phrase in Shanghainese. That’s where my family’s from, Shanghai. It’s essentially translates to money has to be used on the knife’s edge. 还是得把钱用在刀刃上。And it really meant if you can avoid spending your money, do so. So money was really only used for necessary purchases. I think it developed a pretty like big scarcity mindset in my head that I never knew where the next dollar was coming from. I had to squirrel away all of my savings for later in case of a rainy day, so I’ve always been really good at that. But there were certainly no conversations around investing or growing my money, or demanding my worth and asking for more. Like my parents were there to survive. They were not there to make waves or ask for more. They were happy to just get what they could get.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:07] So when you come out of college then and you end up in JPMorgan Chase as an equity trader, what’s going through your mind when you say, like, this is the path I want to step into?

Vivian Tu: [00:10:17] Like, mama, I made it like, right? Not just that, like I had made it, but like, this is the American dream, right? Like daughter of two immigrant parents. I went to public school. I did not have a college counselor helping me write those essays. I go to the University of Chicago. I get this fancy degree. I get the fancy job. Like I made it. I felt like I had won, like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Golden Ticket style had found my one way into being a rich person. I really that’s what I thought.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:50] So two and a half years into that fantasy of being a rich person.

Vivian Tu: [00:10:56] [laughs] Fantasy is a great way to put it, right, right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:58] Everything kind of implodes because like, the money is there.

Vivian Tu: [00:11:01] Oh, frankly, it wasn’t.

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:03] Right because that early in that career it probably like you’re not quite like at that place yet, but um, two and a half years in, like, you have this dream job, you have the thing where you’re like, like you just described. Mom, I made it, right? Yeah, but something is going so wrong that you decide you have to exit this.

Vivian Tu: [00:11:17] Yeah. So full transparency. I think my very first year, my salary was $80,000. I got a $10,000 signing bonus to move from Chicago to New York. And that was more money than I had ever seen in my life. I thought I was a ka-trillionaire, I thought I was Jeff Bezos, but in reality, I was working a 14 to 16-hour day every single day. And it was actually okay. For the first year and a half, I didn’t mind that I was working crazy hours. I felt like I was being paid, so I was like, fine with it. But it all changed when the head of my desk got let go. And when there’s a shakeup like that on Wall Street, the expectation is that the team that the old boss brought in, they probably weren’t super safe in their seats. So basically half of the team gets let go, new boss comes in, brings in a bunch of his cronies. And initially when I had shown up to my desk to my job, there were 30 to 40 white men and my manager. My manager was another Asian woman. I for the first time saw someone who looked like me succeed in this industry, and it was so reassuring that I could do it because she had done it and we looked the same.

Vivian Tu: [00:12:32] But when I was taken away from her to go work for another guy, it started to spiral out of control. When this man started to make comments about my appearance. Things like you’re too girly to be here. Didn’t like how my fingernails click clacked on the keyboard. Didn’t like that I liked pink. Didn’t like that I was just not one of the boys. And unfortunately for me, that wasn’t going to change for me anytime soon. So I’m like, what am I supposed to do about these characteristics, about myself that he hates when this is the guy who determines how much money I make at the end of the year. And one day I came into work with a long cardigan on and he looks me in the eye. He touches his hands together and he bows and he says, is that a kimono? All I could think was how much I wanted to, like, strangle him. Did not do so, obviously. But it’s one of those moments when a lump forms in your throat and your face gets hot and there’s not much you can say. But I decided at that very moment I was like, I’m out of here.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:35] When you were thinking about where to go from there, did you have the lens that well, you know, the entire industry is kind of like this, so I need to completely exit the industry. Or was there a moment which, you know, you ended up doing, but was there something in you that said, well, maybe there’s another angle, another spot, another place, another shop where I could stay in this because it’s interesting. There’s potential here. I’m curious about that. Yeah. Because you had gotten it to this place. You’d worked so hard, things weren’t happening the way that you wanted them to happen in that particular moment. And it was it was people related. Yet when you zoom the lens out and look at an industry like that, I’m wondering if you’re looking at that and saying, pretty much anywhere I go, it’s probably going to be the same. So like, why bother staying and just going in? I’m curious around that sort of like decision-making window.

Vivian Tu: [00:14:24] I feel like my mom put you up to that question.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:28] [laughs] Ee just got off the phone actually.

Vivian Tu: [00:14:30] Yeah, right. I know that’s exactly what you know. Everyone was basically being like, it’s just a person thing. You still need to work in finance. Like you should go find a different job, just, you know, but still do the same thing because you work so hard and you already put so much time and like, effort. And my parents were saying, like, we helped you get through a college degree that was a quarter of $1 million. Like, you’re not about to like, just piss this away. And I will say out of a place of probably like naivety, like I was still recruiting for other finance jobs. Mostly, I would say at hedge funds, a couple other sell-side opportunities. But I really was going to take the first offer. I got to get out of there. And coincidentally, for me, it ended up being in a media company. I went to BuzzFeed. But I’ll be totally honest, I was interviewing with a handful of hedge funds and was getting to like final round interviews with them. It just the timing was running a little slow for good reason too, because they’d be like, hey, can you come in for an interview? I’m like, okay, let me think of like, what excuse I can make up to, like go to this interview because I couldn’t be like, hey, I have to leave work early.

Vivian Tu: [00:15:44] People would be like, you’re supposed to be here 14 hours a day. What do you mean, leave work early? It’s like, well, I have to go to this interview. So I was making up excuses of doctor’s appointments. And, you know, my mom is in town. Like, there was just so many angles that made interviewing at these companies very challenging. But I think I’m really lucky with how it ended up playing out. But I certainly did feel sad to be leaving the industry after putting in that much work, especially because everyone in my life was telling me the exact same thing that you were asking me of. Why let it all go to waste after working so hard after going to UChicago? It’s known to be a Wall Street feeder school after, you know, getting the good grades, after going through like a dozen of interviews to literally land that one seat, like, how do you give it all up? And it’s like at a certain point you have to recognize what is in your best interest because everyone around you has an opinion, but they’re not the one sitting at that desk for 14 to 16 hours a day wanting to pull their hair out. It’s you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:45] Yeah. I mean, it’s the classic sunk cost fallacy, right? It’s sort of like I put so much into this. So many years, so much money. So many people have sacrificed on behalf of, like, making, getting me to this place. How could I possibly walk away from it? No matter how miserable I am and no matter how little hope I see of it changing. But yet I’m so invested in it, we feel like we’re just we are locked into the investments that we’ve made in the past that brought us to this place, rather than looking at the future and saying, but look at the runway I have ahead of me. Yeah, our psychology is so weird around this.

Vivian Tu: [00:17:16] And can I tell you, I have friends from my analyst class. So basically all of like the people my age that started with me who watched me leave were like, congrats on leaving. I can’t believe you did that. And now it’s been, what, 4 or 5 years since I’ve left? They are still in those jobs, and they are still complaining to me about how they’re going to leave, about how they want to leave. And I’m like, you’ve been saying this for five years, and truly now at this point, you are actually at, you know, a VP level, like it’s going to be harder every year to leave because suddenly your compensation isn’t just your salary and your bonus. It’s got an equity package that vests over four years, and now your golden handcuffed to a job or to a shop. And I feel lucky to have gotten out when I did. But there are certainly people who made fun of me when I did it. It wasn’t something that people supported. And now looking back, there are still people who wish they could have done what I did and are still kind of stuck on that hamster wheel.

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:21] Yeah, it is such a tough decision. We share sort of like an odd similarity in that. So I was for I had a hot minute career for five years as a lawyer in New York City, and I was working in one of the giant firms same hours that you were describing 14, 16-hour days, seven hours a week. And I got to a place where I was just so physically and mentally burnt. I was kind of wrecked that I made that same decision, even though I had the job that from the outside looking in, everyone’s like, that’s the job that we aspire to. I knew that like every day that I stayed there longer was maybe it was going to add to my bank account because I literally didn’t have a life where I could spend the money that was coming into it. But if I didn’t have a life, it really didn’t matter anymore. And I exited that and completely left the entire field of law as well. So I’m fascinated by folks who make that decision because I know it can be really hard. There’s a lot of social judgment that often comes along with it, as well as your own internal clock saying, am I doing right? Not just by me, but by those who have supported me to get here. And that sometimes can be a voice which is stronger than your own voice, where personally you’d be willing to take a risk. So it’s it’s awesome to sort of like hear the inner thinking around those decisions, because I think people don’t often share, sort of like, here’s how I thought through it, and here’s what I dealt with along the way. So you end up, as you described at BuzzFeed. Um, from what I understand, um, digital sales. And while you’re there, you start to realize, wait a minute. All of my colleagues are, like, asking me all these money-based questions.

Vivian Tu: [00:19:53] Yeah. You know, I was one desperate for friendship because I didn’t know anybody. So I would sit with a random group of people every single day at lunch, ingratiate myself, be like, what are your names? What do you do? Like try to learn as much about people as I could, and they would ask like, oh, like, what company did you come from? And their assumption was that the answer would be something like, oh, like a, I came from vice or now this or other, you know, a competing media company. And when I would say, oh, I came from Wall Street like I was a trader, they’d be like, what? Like that doesn’t make any sense. And I would explain my career trajectory. And then the immediate follow-up question would be, can you help me rebalance my 401k? Or should we be buying our company stock options? Or which health insurance plan did you pick? Can I just see what selection you made for open enrollment? I’m just going to copy yours. And it was so funny to me because this would be the same three questions that I would get from people who were younger than me, fresh out of college, but also people who were well into their 30s and 40s and very senior, making way more money than I was. And I’m like, wait, you probably make like two, three, four times as much money as I do. How do you not know this? And it made me realize that nobody really gets the financial education that they deserve and or need.

Vivian Tu: [00:21:13] And the only reason that I had gotten it wasn’t even because I’d worked on Wall Street. It was because my very first manager, my very first mentor, the Asian woman I mentioned, her name is Jean. She took me aside and she took me under her wing and basically asked me all of these questions like, are you contributing to your 401 K? Are you using the company benefits to pay for your healthcare? Are you doing this? Are you doing that? And obviously I wasn’t, but she walked me through it and I almost joke that instead of a rich dad, poor dad situation, I was like, I had a rich mom, poor mom situation. And that, like, my parents were able to really teach me about that saving and budgeting piece. But Jeannie was the first person to show me how to grow my money, how to hit conventional wealth in a way that, you know, we envision showed me how to invest, showed me how to do all those things. And now I was able to then pass that on to my co-workers. And what I ended up doing is putting it on the internet, because I was getting the same question so many times. I didn’t want to repeat myself, but little did I know, more than just my coworkers needed that information.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:19] Yeah, I mean, so you start posting. It sounds like pretty quickly a lot of people start paying attention.

Vivian Tu: [00:22:23] First video. Very first video.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:25] That one kind of exploded. Was that a shock for you?

Vivian Tu: [00:22:28] Yeah, because the very first video, like I did not have an editor, I did not have anything fancy. It was like me, my arm and my phone. I had a little script and I basically just said, hey, it’s the middle of the pandemic. I’m seeing a lot of BS going around on the internet. You shouldn’t listen like I do not have a get-rich-quick scheme, but I can teach you about personal finance. It’s not that complicated. I used to work on Wall Street. I can explain it to you and instantaneously. A couple hours later I had thousands of followers, thousands of comments, and by the end of the week, that video had gotten like, I want to say like 3 million views. And I had 100,000 followers on TikTok. And it was a very much an oh no moment. Like, how am I going to keep up with the demands? And like the thousands of questions I’ve gotten and it started to just be like, hey, just take the next step. Don’t worry about what’s, you know, a mile ahead or two miles ahead or five miles ahead. But just answer one more question today. And that’s how the content started.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:28] Yeah. I mean, and now, you know, there’s literally just a handful of years later, three years later or so, like, as we have this conversation, you’ve built a global community where you’re in there serving every single day and answering a lot of questions. It sounds like part of what you realize goes back to the earlier part of our conversation, too, which is that, yes, a lot of people don’t know this information, but also particular communities of people really don’t know this information. It’s almost like there’s a there’s a gatekeeping effect, and it sounds like part of what you start to step into is let me not just kind of show what I know, but I really want to actually heal a chasm here. There’s a very particular thing that I want to speak to, and there’s information that I want to get into the hands of particular groups and communities of people.

Vivian Tu: [00:24:09] Yeah, I love that you bring that up because there is so much emphasis. I call my audience the BFFs, and I’ve lovingly dubbed them The Leftovers because for so long, if you weren’t an old rich white guy wearing a Patagonia vest on CNBC, financial services didn’t cater to you. If you were a woman, you weren’t even allowed to have a credit card in your own name until the mid 70s. If you were a person of color, it was totally. Possible that your community would be redlined and you would be prevented through unethical and certainly illegal means from buying a home in certain neighborhoods. If you were a part of an LGBTQ couple and you walked into a bank to try to get a mortgage. Odds are good you would be discriminated against. You would get a higher mortgage rate with worse terms than if you were part of a heterosexual couple, and people have not had the same opportunities. So I think it’s really important to call out these injustices as well as just make this financial information accessible and understandable, because anybody can Google the financial rules. But I talk about this in my book Rich AF. Like we don’t need just the rules. We need to be taught a strategy, a financial strategy, because you can learn the rules, but you still don’t know how to play the game.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:28] Riffing off that last word game in one of your lenses is like, well, this is kind of a game. And like any game, there are cheats, there are loopholes. And this isn’t like slick, gimmicky type of things. But there are actually there are techniques. There are things that people are just not aware of, that people who have access to different information, to different advisors, to different circumstances are. And one of the things you address is sort of like the power of loopholes when you’re really thinking about like, how do I develop a strategy?

Vivian Tu: [00:25:57] Yeah, I will say this tax codes, financial strategies, career how-tos, how-to budgets, savings, loopholes, anything like that. These were all written by rich people for rich people. And they’ve passed these secrets down in their communities for generations. But many of us don’t know these things. Did you know that you can be taxed less if you contribute to a retirement account? Now suddenly it’s not just today you taking care of future you, but it’s also today you getting a tax break for doing so. You know, do people understand how high-yield savings accounts offer so much more in earnable interest than a traditional brick-and-mortar savings account? If you didn’t know that, you’re missing out and you’re still giving your bank a near interest-free loan, did you know that if you set up direct deposit so that a percentage of your paycheck goes towards a specific savings account instead of all into your checking account, psychologically you are less likely to dip into that money. You’re going to be a better budgeter. You’re going to be able to save more. You’re going to be able to save on your taxes. You’re going to be able to invest. All of these are secrets, but they shouldn’t be. They should be easily accessible to the public. And I just, you know, really think that this information should be taught in public schools. And until it is, I’m going to be shouting it from the rooftops.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:17] So here’s my question then why do you think it’s not? Because it seems like this is information that everybody should know. It’s almost like it’s expressly not taught at, you know, reasonably at an age where people are old enough to understand it and to start to actually act on it, but young enough where if they built certain practices and behaviors into their lives, that it’s really going to make a huge difference over time.

Vivian Tu: [00:27:39] Jonathan, if it is taught federally in schools, who benefits? It’s not the people at the top. It’s not corporations, people who have money. Right now. People who are in power are not incentivized to teach this to the general public. I absolutely hate to sound like tinfoil hat conspiracy theorist, but like by keeping some of this information inaccessible or so jargony that regular person can’t understand it. Or behind a gate-kept wall like we keep our working class working. Somebody has to pump my gas, somebody has to go deliver my DoorDash, somebody has to bag my groceries. And to keep people in these minimum wage jobs in positions where they work, you know, 16 hours a day and don’t see their kids in dangerous and grueling labor that is backbreaking. They can’t know better. And that sucks to say, because we’ve seen it time and time again. These people that are paid the least in our societies often are considered the most crucial, the most essential. I mean, look at Covid 19, right? All of us white-collar employees, we went home. I stood at my little standing desk. I’m like, oh my gosh, unprecedented times to all of my clients. We joked about how we were making sourdough and that whipped coffee. But what about the construction workers? What about the delivery drivers? What about the people who were, you know, picking up the garbage on the side of the street? What about the people who had to go into the hospitals to work, you know, a 24-hour shift as a nurse, like all of these people who likely make less than I did, were forced to go into work under very dangerous situations when they likely didn’t have the right, you know, precautionary tools to take care of them and keep them safe.

Vivian Tu: [00:29:22] And we’re asked to work for much, much less. And people don’t put themselves at risk. People are smart to recognize that, like they are going to buy the best life that they can. They’re going to have the best career. They’re going to have the best house. They’re going to have the best relationship with their kids that money can buy. And if they have the opportunity to do better. They’re not going to keep doing something that is dangerous or precarious, in the same way that when people were getting $2,000 stimulus checks, DoorDash had a shortage of people willing to drive. Because when you have the ability to make a decision out of a place of abundance, and you can take that extra week to find not just a job, but the right job, you don’t want to work the shitty jobs. And so we don’t teach financial literacy at a federal level because people in power corporations, the people who have the dollars to lobby for it, don’t have any incentive to.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:12] Yeah. I mean, when you sort of zoom the lens out like that, it’s sobering.

Vivian Tu: [00:30:16] Sorry, that was really dark.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:17] But it’s sobering. And a lot of what you’re talking about is like, well, okay, if nobody else is going to do it or if it’s not going to be delivered in sort of like a, a standardized educational way, let me actually play the role of the teacher for everybody else. Yeah. Um, let me share what I figured out. And one of the things you also talk about is really just riffing on what you were talking about is this notion of knowing your worth, you know, understanding that there’s a value that I bring to the table. And it’s interesting, right? Because you were just describing a scenario where in the last 3 to 4 years, there’s been this huge shift in power dynamics in the workforce and during the pandemic, and sort of like the emergence the last 2022 ish, a lot of power still remained in the workforce. And because there was a shortage and now I feel like the pendulum has started to swing back, you know, and now people are in this really funky moment where they’re like, ooh, you know, like there’s there was a year and a half to two years where people were tripping over themselves to find people like me. And I could basically say, this is what I want. And people would say, yes, please start tomorrow. And now a lot of people are feeling the pendulum swinging back where the power is shifting again. So we’re in this really funky moment. So when you talk about, you know, the importance of knowing your worth and then asking for it and negotiating it, how do you think about this moment?

Vivian Tu: [00:31:40] I think these macro trends are always going to be occurring. Either it’s going to be mid-great resignation, where everyone can basically say, I want $1 trillion and their boss will say, fine. Or to your point, as the pendulum swings the other way right now, where it feels like almost like, you know, the great layoffs, people feel very, very worried about job security at the end of the day, what I like to remind everyone is that the top performer never gets fired. Never. If you are performing at that high level, if you are out selling, outperforming the people you sit around, the people who are in your team, you will always be safe. And it’s really important to acknowledge that even during times of instability, at a broader level, if you are a strong performer, you can still ask for more money because you still have value and you still have worth, and you are providing something that that company needs. And I think it’s okay to ask, because even if you get told no, you’re no worse off than you were 20s beforehand. And so I think regardless of the year, regardless of the environment, you can still ask and I recommend people ask for 10 to 15% raises every single year, as long as they are performing to that level.

Vivian Tu: [00:33:01] Am I saying you’re going to get that every single year? Not necessarily. But if you don’t get a raise, the same percent that inflation is currently at, you know, at one point it was at like eight 9%. I think right now it’s come in a little bit closer to like 5%. If you’re not getting a raise equivalent to that of inflation, you’re actually going to make less next year than you did this year. And so not only is it critically important to make sure your pay keeps up with inflation, but also seeing how much your corporation values you through pay is a very healthy marker to understand where you sit. And if you have been told year after year, your performance is not where it needs to be to get that raise that tells you something. Or if they consistently say, hey, you’re our top performer, but we don’t have budget, that also tells you something. Maybe it’s time to go somewhere where they will have budget to pay a top performer like you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:33:50] I’d love to get granular for a moment. If you’re open to this. Let’s say somebody is listening to this and they’re like, let’s do it. Yeah, okay. That makes sense to me. And I actually have been a top performer, you know, like there’s been a lot of change, a lot of shifting. But I’m the one who keeps staying here and I feel like I’m doing really good work. But also I see the macro trend here. I see the impact on my company or my team or my division, whatever it is. And I know things are tight, but I still need what I need. Yeah, what would be some basic language that somebody might be able to actually step into to sort of like open this conversation?

Vivian Tu: [00:34:22] Yeah. First and foremost, I highly recommend everybody create a brag book promo pitch raise receipts folder in their email. Essentially, any time you get an email that pats you on the back saying, hey, we could not have gotten this project done without Jonathan. Like Vivian is the best designer on this entire team. Like whatever forward those emails. That way you essentially have a Rolodex of all of the times you knocked it out of the park, and it’s very easy to quantify your successes. I would then set time with your manager 6 to 8 months before your end-of-year review or mid-year review. That’s when you start asking for money, because what everyone likes to do is they wait until November or December and they are too afraid to ask throughout the year. So they, like, bottle it up, bottle it up, and then it starts to bubble to the surface, bubble to the surface, bubble to the surface. And you get to December and you’re like, if I don’t get a raise next year, I’m gonna quit. And your boss is like, where is this coming from? Like, we’ve never talked about this. It feels so out of left field. Whereas if you start six months in advance, eight months in advance, and don’t be annoying, but be persistent, remind them every two months that, hey, these are the goals that I’m setting. Here’s how I’m tracking to reach them. Additionally, I would like or, you know, a raise of XYZ would be commensurate to the type of work and the level that I’m operating at.

Vivian Tu: [00:35:48] Remind them that pay is important to you because they need to know. They need to know that you are always going to be keeping your eye on that dollar sign. And that way when October comes and HR pulls your manager into a back room and is like, this is your budget, you have to now divvy this budget across your entire team. You understand that your boss is going to have you top of mind because you’ve been asking for the past, you know, 6 to 8 months. You’ve probably touched base with them 2 or 3 times. They know you care about money. You’re going to be top of their mind, whereas everyone else is going to be an afterthought because they haven’t asked. Essentially, you have to tell people you’re going to do good work, do the good work, and then take a megaphone and remind everyone of the amazing work you did so that you can be first in line to get that money, because you don’t get paid by putting your head down and being the smartest person in the room. There has been statistic research that the person with the highest IQ is not the one paid the most, it is the person who makes the hardest effort to be known socially, and people think they do more than they actually do.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:48] That last part, um, being known socially is really interesting, especially right now when the shape of work is changing in dramatic ways, where some people in the office, some people are at home, some people are some blend. And that’s really changing very quickly, too. And one of the big concerns has been, well, if I’m not sort of like physically present in front of the people with whom I have to not necessarily curry favor, but just become known on a regular basis for who I am and what I contribute, that it’s going to make it that much harder. And what you’re describing is sort of like, well, even if you’re working entirely remotely, if you’re building your brag file, if you are having the meetings or the conversations where you’re in control of the mechanisms to regularly show people how you show up and what you contribute, then it kind of helps offset the fact that you might not be physically present in the office. Does that make sense?

Vivian Tu: [00:37:43] Yeah. Um, you know, there’s in my mind a concept of like no face time, no pay. And I think that’s true. It’s really easy to have those little fun water cooler moments when you’re in person. Right? It’s as simple as asking somebody on your team to go grab a coffee in the afternoon. If you are working fully remote or even hybrid, you don’t get as many swings at bat, is what I call it, to have those face time moments. So if you know that for a fact, you need to be going out of your way to strategically schedule time not just with your boss, but with people who could potentially do you favors. So when I got to BuzzFeed, I did not know anything about media, couldn’t tell you what an impression was, had no idea how to sell something. I just didn’t know anything. I noticed that there was a social hierarchy, and if you were a part of this upper inner circle of salespeople who closed, who were just known for closing monster deals, always, you know, being at the top of their game, people would bend over backwards for them. And what I did was every day I would spend 15 minutes getting to know someone new on a team that I had to work with tangentially. Not my team, someone tangentially. So I would go out of my way to meet the people in accounting, who were the ones who were making sure that our clients paid us.

Vivian Tu: [00:39:08] I would meet the people in legal who had to make sure that the contracts were signed. I would meet the people in the brand planning team that would help make really big decks and make them fancy. I would meet the people on the distribution team or the social team or whatever, and that way when I needed a favor, I had put in all this face time, which you can still do remotely. Just ask to set up a 15-minute coffee chat to get to know someone. It’s a little harder, but it’s not, you know, impossible. But because these people knew me. Because they knew. That I like to go to Pilates on Friday afternoon. They knew that I cared about the new Goldendoodle dog. They got that I knew what their kid’s name was when I needed a favor. When I needed something done in four minutes instead of four hours, I had a favor to call in, and that made me more effective at my job and putting in all that face time got me paid more. So I do think it’s important to build those relationships. I think with the rise of hybrid and remote work, we’ve started to take that for granted, that we always like to do stuff for people we like, and you’re more likely to do something for a friend than you are a stranger.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:16] Yeah, I mean, that makes so much sense. So here’s what’s coming up in my mind as you’re describing this, a third or so of the population identify as being introverted, and what you’re describing is something where somebody’s listening to this. It sounds very much like the extroverted ideal gets the reward. What if that’s not you? What if you’re the person who you’re like, you know, like you’re actually pretty chill, like you prefer not to be very sort of like, proactively and aggressively social. And it actually is really depleting for you. Do you feel like there’s a disadvantage?

Vivian Tu: [00:40:52] 100% there is a disadvantage if you are not the conventional description of confident of a leader. And this isn’t just necessarily like visually, because that has been the case for me. Like being a young Asian woman has been a disadvantage in that. Like people immediately assume that I’m going to be quiet and demure and going to take a back seat. But it’s also your personality. People who are introverted, people who are neurodivergent learn differently, need different ways to process information. It’s harder for them. It’s always going to be harder for certain people. And if you are not the conventional, confident, loud, willing to raise your hand, willing to go to the happy hour after work and schmooze with people because you happen to have kids or a family or other obligations, it is harder for you. And I don’t think that we acknowledge that enough. I think there are certain things that you can do to still counteract that, whether it’s instead of, you know, doing that big group happy hour, it’s setting that 15 minutes aside one-on-one with people, or even asking for a more extroverted coworker or friend to introduce you to someone. There are ways you can work around it, but I’m not going to lie when I say it’s harder if you are not a conventional learner, if you are not the conventional description of what a confident leading manager looks like, corporate work is harder for you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:15] Yeah. I mean, it’s so interesting because that’s me, by the way. I’m raising my hand here.

Vivian Tu: [00:42:19] You really?

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:20] Yeah.

Vivian Tu: [00:42:20] Introverted.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:21] Oh, 100%. Yeah. And

Vivian Tu: [00:42:23] You know you’re a podcast host, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:25] I do know that. But at the same time, what are we doing? We’re having just like an individual conversation. Yeah. Right. Yeah. So I found ways to build relationships, to build a community, to build business, to build in a way that accommodates my orientation, where I can end each day not feeling empty and depleted, but actually I feel good and still build really deeply meaningful relationships. I think that’s what you’re talking about. It’s like, know this about yourself and know that you may have to step into it differently. And rather than showing up at the happy hour or going out for drinks after work, you know, like literally like ten minutes just in an individual quiet or face-to-face conversation. I’ve actually found that that can be more effective. Yes, because it’s so different. It’s such a different approach. And if you understand how to like, really be present in a conversation with somebody, even for a short amount of time, that is so rare these days that I think it leaves an impression. So I love the idea that you’re saying, let’s acknowledge the fact that some people we start on different starting lines. Yeah, but that doesn’t mean that you’re out of the race. It means that you may have to sort of like step into it differently and think about how you’re going to actually make this happen differently.

Vivian Tu: [00:43:34] Can I tell you no one ever believes me, but I’m kind of an introvert, too, especially as I’ve gotten older. I used to be the queen of networking events. I would like buzz around the room like a butterfly, like a bee. I would get everybody’s contact. Like somehow I was able to do it. As I’ve gotten older, it’s gotten worse. Like, I’m like, I’m not good at this anymore. And I find that I’m so much more effective. To your point, just grabbing a coffee with someone one on one, forcing them to laugh at my like, corny jokes. And then they remember me. And I actually have a system now when I have to go to larger events is I show up early, I show up early. I make sure everybody that needs to know that I was there saw me. You know, I crack a joke or I tell them how pretty their blouse was or whatever. I make sure they know I was there and I’m out of there before that event even hits the halfway mark and the swaths of people start to show up because it gives me anxiety to be in a room with that many people. And it’s like, I. Can barely hear people. You’re yelling. I think it also probably has a lot to do with the fact that, like, I don’t really drink anymore. And in many corporate settings, like alcohol is like a social lubricant. And now that I don’t really utilize it, networking has gotten harder. So again, back to your point. Like, yeah, it is harder for a lot of us, but we’ll find other strategies to make it work.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:02] Yeah. And I think in a weird way, also, I feel like the, um, the move to virtual communication, as hard as it was for people to transition to it because it happens so disruptively it forced everybody to get really comfortable. Now where you have this opportunity to kind of like check in with people in a visual way if you want to even like really quickly in a way that much, people are just much more comfortable doing so. There’s more of a multisensory experience that you can actually drop into. Yeah, I love that. You know, one of the sort of like other categories of things that you talk about in the book is this notion of we’ve been talking a lot about sort of like tracking your career and like the making sure you’ve got enough coming inside, like some of the ideas around that, but also it’s what you do with what you have coming in that makes a really big difference, you know? And like you described earlier in our conversation, a lot of times we think, well, this is really complicated. I’m going to have to spend a ton of time learning how to be a stock picker, learning how to invest, learning how to time the market and gain the market. And when you look at the people who generally like accumulate long-term wealth, as you write about and you talk about all the time, that’s not how it happens.

Vivian Tu: [00:46:11] [laughs] Not even a little bit. Do I have time to tell a quick story?

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:15] Yeah, yeah. Go ahead.

Vivian Tu: [00:46:16] So I mentioned this in my book, but the summer after my internship at JP Morgan, I did my ten weeks. I got my full-time offer. Yay me. And then they canceled my badge. They were like, okay, employment terminated until this next date. You are free and clear to do what you want to do because when you are a Wall Street employee, there are things you can and cannot invest in on your own personal portfolio. And once my employment for that internship was terminated and I knew it wasn’t starting up again until the next June, I was able to invest in whatever I wanted. And that summer I had done a full deep dive research project into a sector. Each in turn was assigned a sector and you had to research three different companies. One which was a long aka something you wanted to buy, one which was a short aka something that you wanted to sell that you thought was a bad investment, and a third, which was like an options play. And for me, I had done so much research into a specific biotech company, I’m not going to name names. I was so excited. I had run my project through the research analyst. They had basically said, everything you’re saying is sound. They had prepped me for my meeting. Just because I may or may not have sucked up to them with a coffee and a donut. But I did this presentation. I will be honest, it was one of the best intern presentations. The sales team was then asked to basically ask questions and try to poke holes in your thesis. Couldn’t get through mine. It was a brick wall. It was solid. And I got back to school and I was like, let me put this trade in action, baby.

Vivian Tu: [00:47:54] I took 50% of what I earned that summer. I put it all into this one stock because I was so confident there was no way I was going to be wrong. There was no way. So that miracle drug that they were working on, it didn’t pass phase three trials and the stock price halved in like a 24-hour period. And I was just like half of my, you know, a quarter of my internship money was gone. And I had earned that money through blood, sweat and tears. I worked weekends when I was an intern. I was like, this is horrible. But for me to feel like poof, you know, two $3,000 are just gone overnight. It was a brutal lesson to learn, but in the grand scheme of things, a pretty affordable and cheap one, because I could have put way more money in. But it taught me that there is no such thing as the perfect investment. There are hedge funds, there are brilliant geniuses whose entire job is to find the perfect investment, the best investment. And they get it wrong all the time. And they have more resources, more time, more technology, full teams of people who are reading through financial statements and they still get it wrong. The amount of time and effort that takes to then be wrong, a pretty fair portion of the time does not make any sense. The people who are able to grow their wealth and grow it consistently have a diversified portfolio of index funds, target date, retirement funds, mutual funds, whatever. They’re essentially just making a bet on the overall health of the American economy or the global economy or a certain sector. They’re not trying to pick the perfect company. They’re not trying to do that, because oftentimes you’ll be wrong.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:34] Yeah. It goes against all the mythology. Yeah. It also goes against the mythology that says that there are a group of people who know better than you. They don’t. I mean, I remember years ago, the Wall Street Journal used to do this thing where they would pit these expert stock pickers against a dartboard where they would just put a paper, the Wall Street Journal, up and throw a dart, and then they would say, like, okay, we’re buying the whatever the dart landed on. And the dart often beat the top experts in the world. And I have a feeling they stopped doing that because they’re probably getting too much. I don’t know what happened there, but it ended eventually. But, you know, it really it’s sobering when you think, wow, if you’re really in this, you actually don’t have to do all that. You don’t have to do all this thing. Yes, like study if you want to. And for a lot of people, it’s just interesting. It’s fascinating to follow along. But what you’re you’re describing, what you talk about all the time when we write about in the book is really let’s keep it a lot simpler than that. You’re like, spend your life doing the thing that you want to do, like focus on, like your relationship, your life, your work, all that other stuff. And. Put your money and your basic index fund and S&P 500 something like this, and take a really long-term perspective here. Let it ride. Know that any given year it’s going to be up, it’s going to be down.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:43] But when you look at ten years or 20 years or 30, there has been a historical trend that is nobody’s going to guarantee it’s going to continue, but it’s most likely to. And so I love the fact that a lot of what you talk about is sort of like, can we dismantle some of the crazy mythology about what you have to do to actually slowly accumulate wealth and talk about the reality of the fact that it’s actually pretty straightforward? There are step-by-step things that anybody can do. It’s similar to the way you describe saving. You know, they’re really simple things that you can do. Earlier in our conversation, you mentioned the simple shift between having to make an intentional decision every paycheck to set aside money to invest versus just making it automatic, you know, and as you described, there’s a research that shows there’s a huge difference in what happens when you just make one decision to make it automatic and then let it ride for years or decades, you know, like it is profoundly different. Um, is there when you think about this sort of what to do with your money side of things? Is there like one big myth or misnomer that really jumps out at you, that bothers you, that like you’d want to speak to? Or is it really just sort of like the accumulation of a lot of just little bits of misinformation that stop us from doing what we need to do?

Vivian Tu: [00:51:54] I would say it’s more like death by a thousand paper cuts. It’s all these little bits of information that people are just missing along the way. I think finance is very, very challenging because it’s almost like speaking a new language. The jargon is so heavy, it’s not abundantly clear what a 401 K is based on the name. If you don’t already know what a 401 K is, it’s not abundantly clear what the Roth in Roth IRA stands for, if you don’t already know. And once you do understand the jargon, it’s just really about setting healthy habits in place. But I do think one of the biggest myths is that only rich people can invest. Because how do you think those rich people got rich in the first place? They were investing. It’s not something that you wait to do later, it’s how you get there. I joke that investing is the only way a single person can be a two-household income, because not only are you working hard for your money, your money is working hard for you. It’s like having a great spouse who also brings in money and helps support the family of one, without having to actually go out and date and find that person, what have you. But it just allows you to make money while you sleep. Because we as humans can feasibly only work so many hours a day. We are made of flesh and bones. Our brains do give out after a certain point. You are not as good of a money-making tool as your money. Your money is a better use, so the faster you can get to your money, making you more money versus your body or your brain making you more money, the better.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:35] If you are going to say, if somebody comes to you and says, hey, listen, finally, I had a point in my life where I’ve got a little bit of money where I can start doing something with and I know you’re probably going to take an issue with even somebody saying, I’m finally at a point because your whole thing is like, it doesn’t matter even if it’s a dollar or $10. Just start now. Yeah, exactly. Like somebody just says, okay, I just want to know, like, what are the three things? If I could only think about, like, my life is so crazy, so busy. Like, I just want to know what are the three things that might be the biggest levers in what I might think about doing with money, even if it’s small bits of money as it comes in, you know, like every other week in a paycheck. What would you say to them?

Vivian Tu: [00:54:12] Yeah, I would say first and foremost, start an emergency fund. It’s really shitty that the number one reason for bankruptcy in this country is medical debt. That seems like that shouldn’t be the case. You don’t choose to get a kidney stone or cancer or get sick, but it’s important to have an emergency fund in case the wheel falls off your car or your roof caves in. You don’t want to go into mountains of debt just because you couldn’t afford that. So I would say for single people, 3 to 6 months of living expenses is good. If you are a head of household, if you have a mortgage, just some more fixed costs. I would say 6 to 12 months is probably a better bet. So first have that emergency fund. Two not all debt is created equal. I would rank your debt from highest to lowest interest rate, and focus on paying off any debt with an interest rate that’s higher than 7%. First, because that is high-interest rate debt. Typically, anything above that is usually credit card debt, and that debt compounds faster than you will likely be able to earn in capital gains if you were to invest. So really, really, you want to pay off any high interest rate debt as soon as humanly possible. It just snowballs so fast that it’s going to be hard to get under control unless you’re making a concerted effort to pay it down and then last. Definitely not least if you have your emergency fund. If you have paid off that high-interest-rate debt, invest early and often. So this is as simple as putting away a dollar to $5 $10 every month and set it up on an automatic direct deposit from your paycheck to your brokerage.

Vivian Tu: [00:55:51] And there are so many brokerages that allow you to essentially automatically allocate your dollars, and you’re going to want to consider index funds, you’re going to consider index funds that track the S&P 500. You might consider something that tracks the total stock market, something that travel tracks global indices or sectors that you’re passionate about, whether that be tech or the pharma field or maybe not pharma, because I got burned by that. But, um, you know, just whatever sectors you’re really passionate about as well as if you’re really saving and investing for a specific goal, a target date retirement fund might make sense, right? You want to save and invest for retirement. All you have to do is essentially calculate the year where you will turn 6065, whatever, and back into which target date fund makes the most sense for you. And it’s essentially a catered way for you to always be investing in something that makes sense for your age. And that’s again catered to the average person. If you are incredibly high net worth, maybe that doesn’t make sense for you, but it’s a great jump-off point and it’s so easy to do. And worst case, if you really feel like investing is still too complicated, just get a robo advisor to do it for you. You take a quiz about your money goals, what you know, how much money you make, what your goals are when you want to retire, how much money you’re spending, what tax bracket you’re in, whatever. And they will pick investments for you. You just need to start because time in the market beats timing the market or picking the perfect investment every single time.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:19] Yeah, that makes so much sense. So zooming the lens out a little bit, we’ve been talking a lot about money, about wealth, about worth. In your mind, what is the real role of money or wealth in a life well lived?

Vivian Tu: [00:57:34] When I first started thinking about money and wanting to be rich, it was for very shallow reasons. I wanted to be able to buy that new designer purse, drive my lime green Lamborghini. I wanted to have the mansion on the hill. But as I’ve started getting to a position where I’m comfortable saying I’m rich, I live an incredibly good life, I am wealthy, I am doing great. Money has become more of the ability to have optionality in my life. Money is power. Money is agency. Money is being able to take an Uber at 11:00 pm at night without double checking how much money is in my bank account, instead of taking the subway, because I’m not sure if I can afford it. Money is being able to leave a bad boss. Money is being able to leave a bad relationship. Money is being able to leave a bad apartment. It gives you the power and agency to live the life you want to live without fear, because it gives you choices. And so I think it’s so important to encourage people to want money, to want wealth and richness in their life because it gets them out of bad situations and lets them choose exactly how they’re going to live and what a happily ever after means to them.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:49] Love that feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So in this container of Good Life Project, if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Vivian Tu: [00:58:58] To live a good life is to have all of your needs met, and then be able to use the resources that you have to not only bring yourself joy, but help provide that joy to others, that comfort to others, and that security to others. I think it’s all about spreading that wealth, because when you are rich, it is not only your obligation, but it’s your privilege to be able to help others, to be able to spread that wealth, to be able to spread that education so that more of us get to live a good life.

Jonathan Fields: [00:59:33] Mm. Thank you.

Vivian Tu: [00:59:34] Of course.

Jonathan Fields: [00:59:36] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode safe bet you’ll also love the conversation that we had with Patrice Washington about wealth and purpose. You’ll find a link to Patrice’s episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help By Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven-second favor, and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better. So we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.