When was the last time you truly played? Not competed, not achieved, not performed… but simply played? As adults, many of us have forgotten how. We’ve buried our natural instinct for play under layers of productivity demands and social expectations. In this conversation, celebrated toy designer and play expert Cas Holman reveals why rekindling our relationship with play isn’t just about fun, it’s essential for our resilience, creativity, and human connection.

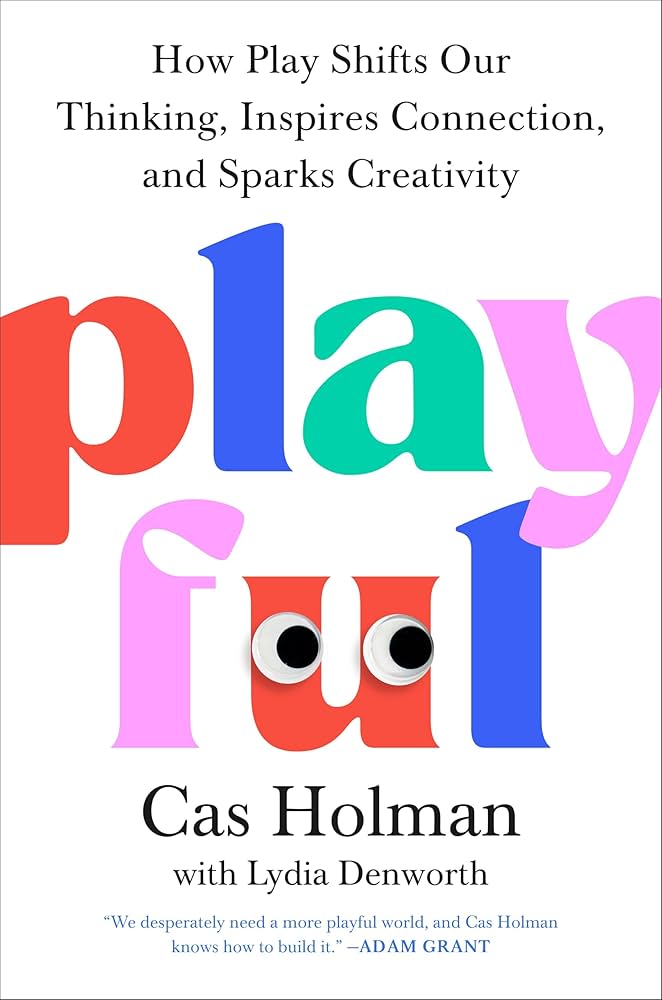

Drawing from her new book Playful: How Play Shifts Our Thinking, Inspires Connection, and Sparks Creativity, Cas shares powerful insights about free play versus gamification, why adults struggle to be playful, and how embracing uncertainty through play can transform our lives and relationships. You’ll learn practical ways to bring more genuine play into your daily life, understand the difference between play and performance, and discover why playing might be one of the most radical acts of self-expression in our achievement-oriented world.

Whether you’re feeling stuck in rigid routines, craving more meaningful connections, or simply wanting to rediscover joy in your everyday experiences, this conversation offers a refreshing perspective on how playfulness can help us navigate life’s challenges while staying true to ourselves.

You can find Cas at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Debbie Millman about designing a life through creativity and story.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Jenna Jones

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:00] So what would happen if you gave yourself permission to play again, not just structured activities or competitive sports, but genuine free spirited play, the kind that makes time disappear and fills you with that lightness of being we so often leave behind in childhood. Turns out, as adults, most of us have kind of pushed play so far to the margins of our lives, we’ve forgotten how transformative and essential it can be, not just for joy and connection, but for our resilience, our creativity, and the ability to navigate uncertainty. My guest today is Cas Holman, founder of toy company heroes Will rise and former professor of industrial design at Risd. She spent decades designing toys and play experiences for organizations like the High Line, Liberty Science Center and companies including Google, Nike, and the Lego Foundation. And her new book, Playful How Play Shifts Our thinking, inspires connection and sparks creativity, challenges everything we think we know about adult play. What fascinated me about this conversation is how Cas reveals play, not just as some sort of nice to have addition to life, but as this vital force for resilience, especially in uncertain times. And she shares stories of bringing eight year olds and 80 year olds together and play, breaking down barriers that words alone couldn’t touch, and offers this completely different fresh take on how we might reconnect with our natural capacity for play. Why it really matters even in the most serious moments in life. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:40] We’ve been having fun starting out these conversations with a little bit of a new five. True or false statement segments. Okay, I’m going to pose five true or false statements to you. And as much as you might want to actually answer with a hedge, to the extent that you can try and answer with just a true or false, and then throughout our conversation, we’ll kind of unpack what we dive into you game?

Cas Holman: [00:02:00] Oh, boy. Okay. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:02] Statement number one play is important for kids, but not for adults.

Cas Holman: [00:02:06] False.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:07] That was a gimme.

Cas Holman: [00:02:08] Piece of cake. Thank you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:10] Number two, if a workplace is built around play, productivity is going to suffer big time.

Cas Holman: [00:02:15] False.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:15] When you’re dealing with serious things in work or life, introducing play is inappropriate if not outright harmful.

Cas Holman: [00:02:22] O false.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:23] Number four. It’s naturally harder for adults to drop into a playful mindset and let go the way we did when we were kids.

Cas Holman: [00:02:31] Very true.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:32] Last one in play. Done right. Everyone’s a winner.

Cas Holman: [00:02:35] True.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:36] All right, so here’s my big opening question for you. Why do us grownups and maybe I shouldn’t include you in that, but why do grownups in general find it so hard to play?

Cas Holman: [00:02:49] Well, it required an entire book, apparently, to answer that question, which I didn’t necessarily expect. I’ve been asked that question by a lot of adults, and I had dodged it to some extent because I felt unqualified. I thought, we need therapy, not a new design. Um, which is also true. I think everyone has their own relationship to cultural norms in our schooling, in the way that we’re raised, whatever version of households we have and family structures. Typically we come up being taught that there are right and wrong answers and that we kind of aspire to be right. We aspire to be good at things. In fact, we spend a lot of our childhood trying to become what we want to be when we grow up and kind of eliminating things along the way if we don’t excel at them. A lot of those things that we eliminate, we actually like quite a bit. A lot of the things that we have to stop doing because they’re not productive or they don’t relate to being graded or getting into college Are things that are really playful and really good for us and feel really good when we do them, but they don’t feel important, so they don’t continue to be priorities.

Cas Holman: [00:04:01] And we’re also, I think as we come up, you know, we learn to hold still, to kind of aspire to be taken seriously. That means to not we learn to not play, and we suppress the kind of instinct and our inner drive to play, which doesn’t mean that it’s not there. It means that we’ve learned to disregard it. I call it a play voice. I think we all still have an inner play voice. It’s just that that voice is not taken as seriously as our adult voice, which is the one that says, no, you can’t go roll down that hill. You can’t like, dance while you’re waiting for gas at the gas station. You know you can’t sing along. There’s people around. We have an interplay voice that’s like beckoning and kind of like, still sees the opportunities and the possibilities of play, but we just kind of ignore it or think it’s, um, not for now.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:50] Yeah. I mean, as you’re describing that the person dancing at the gas station or. Like all these different things. These are movie scenes, right? These are the scenes that we like when we have when there’s that just like person who’s totally free and they just they love themselves and they’ve gotten in touch with their inner child. And, and we see those scenes at the movies and we’re like, ah, that’s awesome. I want to be that person. And I wish I felt that, quote free. And yet, when we step back into our day to day lives, we’re terrified of being that person. And like you said, it sounds like it’s not that we have to learn to be that person again. We have to unlearn not being that person.

Cas Holman: [00:05:24] Exactly, exactly. And I think it doesn’t always have to be grand gestures. I think that there’s a misconception that play is like big and bold and like we but play can be quite pensive. I, I, you know, when I’m walking my dog, I’ll notice in people’s windows what’s going on in their kitchens and kind of imagine what they’re making or what their lives are like. And I think that’s kind of play like that’s imaginative Play or attention play. I think watching birds or even noticing details is a type of play that adults take part in. So there’s all kinds of play that we actually do, whether or not we would call it play or whether or not we like indulge in it, because we often kind of look at our devices instead or think like, oh, I can’t daydream or I can’t space out, right? Everybody else is on their phones. I better look at my phone. You know, I need to feel important or I need to look important or like, ah, this is what we’re doing now, waiting for the subway. So I got to look at my phone, when in fact, taking a beat and resisting the urge to look for entertainment or look to kind of consume play, even in in the types of, um, games and things we might play on our phones, we can tap inside of ourselves with our own attention and create play for ourselves without needing to, you know, look at our phones and perform adult in public.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:42] Yeah. Do you distinguish between play and whimsy?

Cas Holman: [00:06:46] I think Whimsy to me would be a characteristic of playfulness. My understanding of the word is kind of like a lighthearted something, maybe a little bit joyful, or it has a positive connotation. And so I think a lot of play has whimsy in it. And maybe I’ll whimsy is playful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:08] Where do we go wrong here? I mean, what happens between the time that we’re kids, where not only is play celebrated and accepted, but actually, like, it’s literally built into a kid’s day. There’s literally playtime. There is recess in school. There’s all this stuff. Even within the context of classrooms, you know, like, how do we actually play our way to learning the lesson that that I want to actually create in the kids lives? How do we go from literally having an innate impulse to play as a kid, having the people and the environment around us supporting that and saying, this is good, this is awesome, this is helpful. You’re going to develop and be happier. And then at somewhere a point along the way, it’s like the rug gets pulled out from us and said, no, actually, once you hit a certain point in your life, this is not the way to be anymore. And not only that, like, it’s not only not the way to be individually, but also it’s not actually a good thing to keep building environments and cultures that support that. In fact, it’s a bad thing. Like, where does this come from? How does that switch get flipped?

Cas Holman: [00:08:14] Well, I think we’re pretty single minded in our need to be productive, right? I think that we value it’s all about values and we value things that are connected to earning. Right? And that’s a very real need for most people. The need to pay the rent and buy groceries. That feels like the thing we need most for survival. And everything else kind of falls in line with that. Like, I think even the way that we exercise and sleep is now associated to you should exercise because it’ll, you know, meditate so that you can go be more productive at work or sleep better because then you’ll, you know, do better in school or these things. So we tend to like even frame things as value. I mean, look at how we think of time, right? Like time is money. We have all of these ways where we our own behaviors and our time is so directly linked, whether or not we’re aware of it to capital and to this idea of of the need to work, not just that, you know, and work has a different meaning to different people as well. But and so I think that something like play because it’s we don’t understand it as valuable. It’s not a priority. And so it does become kind of the antithesis of what is good, right, or what is valued. I think that we set up our structures accordingly. And I will say, though, that I have seen a shift toward I live in New York, and so I’m seeing more and more streets that are being closed down for the sake of there being more public spaces for people to gather, which I see as a form of play.

Cas Holman: [00:09:47] I think, you know, different communities have different excuses to have parades and festivals and music venues and concerts and things like that. And all of that is adult play in a way that typically there’s, you know, some kind of sponsorship behind it. Of course, in the US, at least in other countries, they have these giant music festivals that are, you know, part of the collective known to be part of the greater good, right? So they happen the same way that like it’s and they’re valued as part of the way what people do and time is taken off or time is given for that. But I think that it has a large part just with like we don’t value it. And so therefore it’s not a priority. And we don’t because we don’t necessarily understand and we’re not connected to our own play. It’s not a thing that we necessarily feel the benefits of. Right? Like when you get enough sleep, you can feel the benefits of that and you feel better the next day. So you’re like, oh, right. That is a thing that makes me feel better. And I think with play, if we can like have enough exposure to it and like get into the start to recognize the places that we do play as play and then give ourselves a little more and more room, then it can become a priority and we will start to value it more and therefore kind of give our let ourselves have the time or in terms of as a collective, dedicate resources to it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:02] It’s so interesting, this relationship you describe between play and productivity. It’s almost like you assume they’re on opposite sides of a duel. It’s like you’re either productive or you’re the playful, but, you know, like never the twain shall meet. So it’s like you have to make a choice. And now that you’re an adult and you’ve got to earn money, and money comes from producing and like, okay, so that’s the thing we have to center. But it really does feel like this false dichotomy. It’s like, but are they really on opposite sides of the seesaw or can they really like coexist and actually or is it really good for them to coexist.

Cas Holman: [00:11:37] Yeah. And they absolutely can. So one of the things that I think is kind of important for me to differentiate is the book is about play in general, but I focus on free play. I think that adults and in talking to people over the last 20 something years in my work, people who reach out and they say, I really miss playing. Like, I know there’s some part of me that would benefit from the same type of play I had as a kid. Like, I remember what that felt like, the flow of it, the like almost spirituality that happens when you connect with yourself while you’re playing and you totally lose track of time, space, like everything, all that matters is whatever thing you’re doing, which is also maybe nothing at all. Right. Free play specifically is something that I designed for, which is different than video games and sports, which are great ways that adults commonly play and also benefit from. But free play is a little different in that it is. I think the biggest difference is intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation and a big part of how we come up in school, which is also related. I think to like the need to earn is extrinsic motivation, right? Like we work really hard. The extrinsic motivator in that is either to get a raise, to earn the money, to get a promotion.

Cas Holman: [00:12:49] When we’re in school, we study in or we study what’s on the test, right? So when we’re children and we’re out playing, children are all free play. They are driven by curiosity and free play. To define it a little bit is a set of behaviors that are freely chosen, intrinsically motivated and personally directed. Again, it’s like it’s something that you want to do. You’re driven to do it from your curiosity and need to explore. And children are doing that all the time, and they’re doing it with their hands, and they’re doing it with their mouth, and there’s smelling the thing and they’re throwing the thing, you know, they want to break it. And all of that is just like an intrinsic curiosity. Then as they come up in school, increasingly they are not learning because they love it and are hungry to understand the world, but because they’re also doing that. But the focus turns to what’s on the test. There’s right and wrong answers. It’s not necessarily about exploring. It shifts up quite a bit to memorize. Understand what we already know we’re not doing great with, like helping children be excited about uncertainty or things we don’t understand, right? In school, they tend to learn things that we already know. It’s like, here’s what we know now.

Cas Holman: [00:14:02] You need to know it, right? And we’re all constructivist learners. Like throughout life, we honor that when we’re in kindergarten. Right. You get to be constructivist and actually build the things and learn with your hands. And then something happens in grade school where we’re like, okay, now we need to like shift it into, away from actually doing. And I think that’s just about the scale. All of these people in the classroom, when you have to get through things quickly and for a lot of reasons, it’s the emphasis shifts to assessment what’s on the test, what’s right and wrong. Right. And so we become pretty uncomfortable with gray areas, which is where play lives. We become very uncomfortable with wrong answers that it was you do it until you do it right or you get it right, and then you’re rewarded. So that’s what makes you feel good. So feeling good and your experience of success becomes linked less to trying and more with achieving or getting it right. Right. This is, I think, why in particular we get acclimated to extrinsic motivation. We have it in our our Fitbit. That’s an extrinsic motivator. Now we we you know you can also take a walk because it feels good. And you see the birds and you chat with your neighbors.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:10] And it’s like you get rewarded. I mean it’s like you get the raise, you know, if you know, by some sort of external metric, you get like all the stuff in life that’s presented to us. It’s like when you check the boxes often that somebody else has created for you. You get this thing that you’re told you’re supposed to want. So it’s sort of like, that’s just the way that life gets structured as you get older.

Cas Holman: [00:15:30] Right? Or culture gets structured? Yeah. And life is attached to culture. But like our person. Yeah. I also experienced this like I, I have a conflicted relationship with the gamification of things because yeah, everything can be playful and yes, make learning playful. But in gamifying things, most of the time we’re just adding an extrinsic motivation to something so that you’re learning in order to win or get more points, but it disconnects you even further from your curiosity about the thing. Now I’m learning it so that I get a point or win a badge, a digital badge, rather than learning it. Because I want to know, and I want to understand how it’s related to everything else I understand or don’t understand. Right. So how does this relate to play? Because freeplay specifically is about saying, what do I need right now? What do I want? And to be in touch with that is actually like helping us this at times, like be attuned to our own needs. Do I need to move my body around? Do I need to sit quietly? Do I need to like stare at a wall? Right.

Cas Holman: [00:16:37] So we’re kind of like tuning in and saying, what do I need? And then how do I get it? I get to figure out what how I, how I am going to move my body around. Like maybe I need to go, like, sweep. That’s what I just did. I was just sweeping the yard, which is I putter, I have a lot of putter play, or maybe I’m going to go across the street and shoot some basketball hoops, or maybe I’m gonna, um, play rowdy with my dog a little bit versus that. You know, a lot of the things that are extrinsic are tracking our time. Now, I keep hearing about the gamification of productivity. And people are like, don’t you like that? That’s making your day playful. And I’m like, is it though? I mean, it’s telling you what to do and when to do it. How is that playful? So you get a digital badge or it beeps at you? I don’t know, is that playful? Maybe that’s gamed, but not play. It’s still telling you what to do and and so no.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:30] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. Hey, here’s my curiosity, okay? And I’m nodding along. I’m like, yeah, this makes total sense. Like, I love it when I get to show up and do something purely for no other reason than a feeling it gives me. I’m not trying to game anything or gain gain anything external. There’s no benefit other than just me loving doing the thing. So business scenario right? There is a car dealership, right? You’ve got 20 salespeople in the car dealership. They’re all trying to hit quota, and the sales manager comes in and says, okay, so we’re going to create a contest, you know, and whoever you know, sells X number of cars gets this special bonus or this special perk, or they get to wear a special jacket and their name goes up on the wall or something like that. Maybe now they’ve taken something where people are showing up largely just for the paycheck. Maybe some people actually kind of really love. They just love the game of selling and figuring out psychology and doing it. Maybe doing right by people. They just genuinely love it, but probably a whole bunch of people there, largely because it’s just the job and they’re doing the thing. Do you feel like then layering this gamification over it, like creating some sort of external thing that people would potentially really want, whether it’s status, whether it’s money, whether it’s whatever it may be, a lot of people would look at that and say, well, isn’t this a good thing? Because then you’re adding another layer that takes something that a lot of people would experience as being kind of mundane without a sense of purpose, and at least giving them a sense of there’s something kind of a little bit more fun or a little bit more playful going on here in this context. Or do you feel like that actually in some way makes it worse?

Cas Holman: [00:19:17] Back to what’s the goal of that, right? So in that case, they gamified something in order to increase sales, right? They weren’t out to, like, necessarily make it more fun and it might have become more fun. So people who hated their job and they were kind of showing up and not trying to sell cars. Maybe now they’re like, okay, I’m going to sell cars now because there’s a contest. I don’t know if that’s going to be more fun. And nothing that you described as playful, right? The goal wasn’t, oh, my salespeople are seem kind of glum. I want to make their lives better by adding an extrinsic motivation to sell things. I think that that’s where it’s kind of like a lot of the Gamifying isn’t setting out to make anybody’s life better, or make people more connected with their peers or their coworkers. In fact, in that scenario, it’s probably going to make the coworkers because they are now competitive. There’s a winner in that version. It is kind of the worst case in terms of mental. You’re not going to make assumptions about people’s mental health, but I don’t think that’s going to make anybody any happier. And there have, in fact been studies about the impact of competition on creativity.

Cas Holman: [00:20:25] And it is like across the board, not helpful. In fact, people are the, um, there was a psychologist who did some research into quite a bit about creativity. Teresa Amabile, and she found that knowing that work was going to be judged or anytime there was competition, the creativity took a huge hit like it was. The work wasn’t as good. People did not enjoy the process at all. They were really glad when it was over versus times that they were told there will be no judge. You have absolute freedom and they wanted to keep going. So in that case, that relates pretty directly to work environments where oftentimes you are working hard toward one event and then you kind of like, ah, and it’s over and you take a break. So I don’t think that competitiveness brings much to that to anybody’s wellness. It may increase sales, which is in fact usually the goal with the manager who brings that sort of thing to the table. But that’s I think that’s a great example of gamification isn’t necessarily about the individual, and it’s definitely not about play.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:23] I mean, it’s interesting also because part of what you’re describing, I feel like it also ties into this concept of the infinite versus the finite game. You know, the infinite game being the game that you play. Not to win or not to get to the end and like and succeed. But the game that you play with, the desire that you hopefully never have to stop playing because it’s just so joyful being in the game itself. Yeah. Versus the finite game where it’s like, okay, there’s an endpoint that you’re working towards. Like, I want to I want to keep leveling up so I can get to the end of this game, which is always interesting because if you’re having so much fun playing a game and it feels good a lot of times to level up, I’m more skilled, I’m more accomplished, I have more tools in my tool belt. Whatever it is, I have more status in the game. And yet the ultimate, the ultimate thing that you’re then striving for is the moment that you no longer are able to do the thing that you’ve been having so much fun doing.

Cas Holman: [00:22:14] If the goal is winning, right? Yeah. So I think in many cases you get to keep going like water. This is one of the I have the three elements that I think will help adults reconnect with replay. And one of them is reframing success. Reframe success, right. If success is winning and the game is over, but you love the process and you’re like, oh man, I’m totally lost. Now what am I going to do with my life? Where will I find fulfillment? Right? But if the goal is, I love this, the game is over, then you keep doing it. I mean, I see this with with sports, with with people. I hear from people who came up playing sports or or, um, I know someone who, who was wanted to be a ballerina. And as soon as they got too tall, everybody was like, well, you can’t be a ballerina now. And they were like, wait, what? Like, I love this. Why do I have to stop? Because I’m tall, right? Or like, with sports, like. All right. Not everybody’s going to go on to be in the Olympics.

Cas Holman: [00:23:07] It doesn’t mean you have to stop playing football or soccer. Our values are a little bit twisted, but by reframing success, it’s like, well, does success look like becoming a professional? Probably not. And the same can be said for art. Does success look like you wind up with a gallery? No. If you love drawing, keep drawing. You know you can show it to people or or not. It could become your shopping list if it’s something that you find fulfillment in. Reframe success and and and stop looking for it to be good or right. Or you know that like in order to give yourself time to do it, to let yourself do it, it has to be something you’re good at. It doesn’t. It can just be something that feels good and you can get a lot out of that. But remove. The second thing is release judgment, right? Release the judgment that we all often are our harshest inner critics. Right? So release judgment of yourself, but also release the assumption that others are going to judge you because you’re an adult who makes bad drawings.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:06] Yeah, I mean, that all makes sense. It’s like if you redefine success as well, I just get to keep doing this thing that I really love doing. Like that is my version of success, and I can do it indefinitely because I’m not striving for some sort of golden ring or something that somebody else says is like, this is what it means when you’re succeeding at this thing. Then as long as you’re like, you can, you’ll just keep finding ways back into it. And I love like the reframe that you also just offered around doing the thing for the feeling is you, rather than doing it because you’re striving towards some sense of mastery. I think we all do feel. We do love feeling like we’re actually getting better at something and feeling more. It’s awesome. Yeah, right. Competence feels great.

Cas Holman: [00:24:47] Yeah. And ambition is very confusing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:50] Right, right. Exactly. Um, I have a friend of mine who has a book out now called In Defense of Dabbling, and she’s like, dude, Karen Walden. And she’s like, just do the thing because you love to do the thing, even though, you know, you may well really kind of suck at it for the entire duration of however long you get to do it, but still just do it. And we really struggle with that because like all the messages that I think we get told, it’s like, unless you’re getting like working towards mastery, it’s just not worth your time.

Cas Holman: [00:25:17] Yeah, yeah. With drawing specifically, I hang out a lot with a five year old and an 11 year old. Mhm. If anybody has a chance to draw with children there’s your audience man. That’s fun. You kind of can’t go wrong. And they’re what they value in a drawing is has nothing to do with what we’ve come to believe. Makes something good. And I love things kind of similarly like I like um, karaoke for this often karaoke isn’t about singing. Well, it’s just about like, effort. It’s about going all in.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:46] Yeah.

Cas Holman: [00:25:47] And maybe bowling is a little bit similar. I don’t typically bowl with people who are good at it, so that’s definitely not the point. Right. So we reframe success as to like who’s going to be fun to hang out with while we, you know, do this weird thing that makes all of us be kind of awkward for a while?

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:03] Do you think there’s a risk, though? Let’s say you start doing something purely for the joy of it. It’s kind of fun. You’re taking pottery classes at your local pottery studio, right? Or let’s use bowling for your example. You do it because you got a couple of goofy friends who love to get together every couple of weeks and just go spend an evening bowling together. None of you are good. You’re just having a great time doing it right. Yeah, but then you’re doing it for six months, and then you’re doing it for a year, and then you start to kind of get like, okay. And then you’re doing it for another year and you’re like, I’m actually pretty good. And then you’re like, all of a sudden you’re in a bowling league when you do it, even if you’re doing it for joy, over time, you may actually get good enough so that that external structure that says there’s another reason to be doing this starts to. It’s like the sirens that lure you into the rocks.

Cas Holman: [00:26:48] I love this as an example, and I think that with the playful mindset, I what would inevitably happen because I too have done this. And like I said, ambition is tricky. And I did play sports. There’s some competitiveness in me, as with many of us. And yeah, when I do something, I want to be good at it often, right. And I check in so I’ll have that instinct. And then so I’ll say like, wow, I’m noticing that I’m getting kind of like embarrassingly attached to the fact that my score is not or like, I’m kind of so I notice, like I’m being wait a minute, this is becoming less fun, for one thing. Or like, I’m getting kind of mad at the friend whose score is better or whatever, right? And then I’ll be like, wow, interesting. Okay, let’s check in. What is the goal here? Is the goal to win, or is the goal to have some quality time with my pals? Right. And if one is inhibiting the other, like the competitiveness or my desire to beat my last month’s score is getting in the way of the goal, which is quality time with my friends, which matters way more than my bowling score. Then I’ll like, take a step and be like, all right, Cas, check in. Let’s reframe. It requires an awareness of our moods or our our like, you know, instinct to want to be good or be frustrated when we, you know, hit a What is it called? The alley. It’s a gutter. The gutter.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:07] The gutter. Yeah. Shows you how often I ball the galley.

Cas Holman: [00:28:10] That’s definitely not it. It’s important to not ever know the lingo to. That helps if you get to invent words along the way. I think that there’s a misconception that in play, everything should be hunky dory and easy and like, feel great. But in fact, because part of what, especially in free play, part of what is required is the releasing judgment and embracing possibility. Embracing possibility is kind of about curiosity and like, I don’t know what’s going to happen. Let’s try and then reframing success, right? Success is fun with my friends, not winning all of those things also, but up against these other habits of the desire to be good, the the maybe need to try to win right in embracing possibility. And when there’s that window where you think like, oh wow, I might be good at this, right? You start to hedge toward these other habits that can be not quite as playful. And we’re vulnerable in those ways, particularly in the trust that is required with the people around us, like when we go dancing. If you’re not a good dancer, often people will have to get a little bit drunk in order to cut loose, right? I hear a lot from people who are like, I’m great at playing after I’ve had a couple drinks, which, you know, okay, we all let off steam. However, what if we could achieve that level of inhibition without the need to drink first, right? So that we could be uninhibited on the way to work or when we’re, you know, taking a road trip with our whole family. I think that part of what I tried to do in the book is figure out, what is it? What are the conditions, and how can we create the conditions for this without our go to tools that we typically use to release inhibition and be in a state that we can be really playful and care less what people think, and be silly and be more open about our, you know, our feelings or make jokes more freely.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:04] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. You just named some of those conditions embracing possibility, releasing judgment, reframing success. I’m nodding along, listening. I’m like, yeah, it’d be awesome if I could just reframe success as just being in it and playing and forgetting about the scorecard and it all being about the feeling I get when I’m doing the thing. And if I could release judgment and let go of having to feel like I have to perform in a particular way, or being seen by other people and not performing up to their expectations, and it’d be great if I could step into this place of possibility. And I’m like, yes, yes, yes. Check, check check. How? Because like, what if you don’t naturally go there? And a lot of the conditions of being a grown up actually are the opposite. They support the opposite behavior. How do we start to actually rewire the conditions so that we can actually do these things?

Cas Holman: [00:30:53] Yeah, I think kind of noticing when you’re setting out to do something that might be different from what you had imagined it being. So for example, if you start cooking dinner and the fish is bad, you thought you were going to have fish and you’re like, I can’t because it’s bad. Like, you can either drive around looking to replace the old fish and be really frustrated and probably hungry, or you can say, okay, was my goal to like, eat this fish? Or was my goal to just make dinner for my friends that are coming over any minute? What have I got right? And remembering, like, you know what? It’s gonna be okay. They will still like me because we’re not going to have the promised fish. Maybe they’ll also laugh, and I’ll involve them in. How are we going to combine these seven ingredients that I have in my fridge? So there’s this again, like coming at anything from a playful mindset means that you’re coming in with kind of a what if sort of attitude and saying like, all right, what if it’s this instead? And always coming back to what is my goal exactly? And maybe your goal was to use up the fish, But I have a feeling then, you know, there’s something. In that case, like. All right, you got to move on, right? Reset. There’s something else here. If you have friends coming over that make something else.

Cas Holman: [00:32:07] But I feel like there’s almost always an opportunity that a playful mindset will help you through something that either whether it’s problem solving in this case, and then, of course, like there’s a much bigger picture function of play, which is building resilience. And also just like staying grounded in who you are and being human as life gets hard, it’s a funny time to be telling people that they should be playing, right? Quite a bit of uncertainty going around, and in fact, this is exactly the time that we should be playing, because play is the thing that makes us more comfortable and uncertainty. Like there’s nothing that’s about to be fixed right now. Like we can’t approach this problem as something we’re going to solve of all the problems that we could be approaching, That’s just not what the world is going to do right now. And what we can do is stay grounded in our communities and ourselves and keep going right and in play. Play itself, and especially free play is about uncertainty. It’s about comfort with like, I don’t know what’s going on. Let’s try this. What about this? Like, okay, reset. How about this instead? And being curious and, um, grabbing the people around you and just kind of being in it together is a huge part of what happens in play.

Jonathan Fields: [00:33:29] I think you write about this also. It’s this notion of, okay, so if you’re living in a in a moment or a season of life or work where it’s all about rigidity, it’s all about rules, it’s all about heaviness, it’s all about just uncertainty and fear that like, play is almost like this micro act of rebellion. It’s almost like saying, I’m acknowledging there’s a lot happening around me that doesn’t feel good to me. And at the same time, if I proactively say, I’m going to take a moment out of my day right now and do something that draws me into this state of play, that’s me saying, even in moments where I feel like I’m being constrained in all sorts of ways, or those around me are being constrained in all sorts of ways which are not okay, and I don’t want that. I still have, like, this microdose of agency that lets me take a hot second out of my life and in some way, shape or form make it good.

Cas Holman: [00:34:24] Yeah. And I would even push that further and say, don’t step out of your life. Be in your life and your play. Continue to to keep play with you in the fight. Right? Like I’m queer. My partner is trans. Things are not comfortable for us. We have some uncertainty and have for some time around us. And the only answer is to keep being. Continue being who we are, how we do it. I mean, queer people have always used play as protest. The Stonewall uprising, for example, was a reaction to oppression, and we mark the occasion with a parade to honor our elders and our peers, their struggle and their pain, but also their joy and love. We play, we dance and gather and dress up, and we mourn and we celebrate. Our play is both how we experience our resilience and how we express it. We’re not going to not play because that’s who. That’s who we are. And I think that’s to all of us are like, play is in all of us in conflict resolution. And this would be a big ask. Like, I don’t expect people who are having a hard time communicating to come together and like, play in order to fix it necessarily. However, I will say for children in play, when they are left to their own devices to resolve conflict, they will.

Cas Holman: [00:35:44] And there’s conflict in play. Absolutely. There’s half of play is negotiating. You watch children play, there’s always like, no, that is not for a fairy. That is for the elephant. No, the spaceship is not going there. There. That is very real conflict. Or I want this. You know I’m using the hammer. No, you can’t have the hammer. You know, whatever. All of the ways. And they’ll resolve it because they want to get back to work. They want to play. And then also, the play itself is a way of understanding people that is much different than verbal communication. And as a designer and as a creative person, like when I collaborate with someone or when I’m making something with somebody, it’s essentially playing that’s like, for me, that’s my primary form of adult play is my work. And when I’m collaborating, I understand someone so much differently. I could sit next to somebody for years and not understand them the way that I do. After just ten minutes of playing in play, we understand people in ways that are so nuanced and human that we haven’t added structure and rules and all of our other complicated grown up ways to.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:56] Yeah, I mean, that makes so much sense. I have, um, a friend of mine runs a foundation called our Lucien, and a lot of what they do is they go into conflict zones, and they’ll go and they’ll bring a whole bunch of oftentimes kids together, oftentimes kids who are on other side, opposite sides of a really major conflict or issue, and they’ll find some public space, like a wall somewhere or even in a refugee camp or something. And they’ll bring them together along with a bunch of local artists, and they’ll make these massive collaborative paintings, murals, and you’ve got these kids who didn’t understand each other like we’re always told stories about, like how they were the enemy in many ways. And all of a sudden, within a short period of time, they’re playing together, they’re collaborating together. They’re seeing each other’s ideas and visions and values through, like the other person’s eyes, just through the act of playing in the form of craft, of painting, of making art together. I think it’s so powerful when you get to do things like that. And yet again, I feel like it’s hard enough to do that as kids. You know, in that situation, you need somebody like a group of people who really facilitating the experience. And I’m sure we’ve all heard about experiences as adults where like there’s some program that brings people together and has people basically in some way, they manufacture an experience where people see the common experiences and history rather than all the things that separate them. Right. A lot of this, though, this gets to something I wanted to touch into also, which is this notion of when you embrace possibility, part of that necessarily means that you also have to embrace uncertainty. You have to step into the space of the unknown. We’re really bad at it and really uncomfortable doing that.

Cas Holman: [00:38:36] Yeah. And I think that’s because that’s that’s the part and parcel with play. If we have more play in our life and if we’re more comfortable playing, I think we’ll will be much more comfortable and uncertainty free. Play it, especially a project that I just did with the UN, the ILO, the International Labor Organization has the International Training Center, so it’s the ITC. Ilo of the UN brought me in for a workshop about the future of learning and obviously because and I’d worked with them before and they love play, and they use play in a lot of their training centers and are in a lot of their process as they work with different countries. This was kind of a peek AI when people were just beginning to kind of tie everything was I mean, it still is. This is two months ago. However, whether or not regardless of the format of learning, the thing we need to learn is each other. And my thesis for this workshop that we did and we brought together, we had eight year olds and people who were between 65 and 82 years old working together and we we paired them one on one. And I set up these different steps throughout the day. But the thesis of the future of learning is learning each other. And it was interesting to have a few different methods. Some were conversational and trying to make it non-hierarchical. This is the other thing about like the beauty of of play, like in and it’s not always easy to create the conditions for non-hierarchical play because so often there’s, you know, a physical advantage in this case with intergenerational play there, the children have an advantage because they’re intuitively driven to play, whereas adults, you know, have the advantage of that.

Cas Holman: [00:40:18] They kind of like have an expert perceived expertise of some kind, or just the habits of an eight year old is used to looking to the 60 year old for what to do. And the 60 year old is used to telling the eight, right. So we had to work pretty hard to set up conditions that were non-hierarchical and where nobody would, would kind of have the instinct to guide, to direct, and at the end of the day, the most powerful moments were when they were making things together, right? So the conversations were playful and there were some other little like they made skits, they had to kind of act out things. All of it was beautiful, but there were just these really quiet moments of them working together on the sets, actually, for their skits. And none of them, you know, the olders in the group weren’t necessarily artists or creative people. The eight year olds, for the most part, all proclaimed that they loved drawing, as most eight year olds do. No one was necessarily in their element, but in play. They all just relaxed.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:23] It’s sort of like if the rules are we’re all out of our element, then we’re all, it’s like it’s normalized, right? And then all of a sudden it’s like, oh yeah, like there’s no expectation I’m going to be good at this or proficient or like I have to perform to some expectation. We’re all just kind of living in the mystery. And and that’s actually like that’s the point.

Cas Holman: [00:41:41] Exactly. And that’s play and that’s uncertainty.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:44] Yeah. And we’ve been talking a little bit more about sort of like this distinction between playing for your own purposes and also collective play, like what happens when we play together. And it sounds like, like these are practices that both of them would be good. Like it would be good to find practices where we can just make play a part of our own lives individually, and also find ways or create the conditions to be able to do this with other people, because it sounds like there are different benefits.

Cas Holman: [00:42:12] For the sake of kind of giving us a collective vocabulary. I define some adult play types. It’s interesting. In early childhood, in particular, I borrow a list of play types from play workers. There’s or trained professionals who work on playground, junk playgrounds and adventure playgrounds. There are a few in the US. They’re all over Europe. Play workers have these play types that they use because they spend a lot of time reflecting and talking about the play with each other and kind of understanding children and observing play as a design professor and teaching design for play for 13 years, I had used these play types, whether my students were designing for children or for adults or for intergenerational play, and hadn’t really critically about, you know, if there needed to be a different version for adults, right. And then when I started writing the book, the thing that made me realize was talking about risk, that made me realize, actually, adults, obviously we play differently. Like developmentally, a 30 year old will play differently than a five year old, right? A five year old plays different than a ten year old because developmentally we’re using play or we we’re getting something different out of play. So developmentally, I knew we were different. But I thought like, the play might be the same.

Cas Holman: [00:43:25] But I realized that one of the big ones is like what we would consider risky play. Like, what’s risky for a child is maybe Be going around the corner from their family at the playground or like 30ft away from their blanket at the beach. Right. And this is back to kind of D.W. Winnicott safe space, right? If you have any experience with Winnicott’s beautiful theories of what is safe and risk and the importance of of risk and play. And the same is said for adults, I think, to be pushed out of our comfort zone. So to step into uncertainty is part of what helps us grow. Like that’s what challenges us, right? That is, there’s still a throughout life to be challenged as part of what makes us feel good again, whether or not we’re good at it. Right. So I was like, well, what’s risky for an adult is actually just playing, right? One of my adult play types is, is behavior play or misbehavior play. And I kind of started to realize that all playing for an adult is misbehaving, which is just such a mess. Like, my hope is that in ten years, I’ll have to revise the book because we’ll all be so playful that it’s no won’t be considered misbehavior for an adult to just, you know, like I said, like sing in public or groove a little bit while you’re waiting for gas.

Cas Holman: [00:44:39] So in the adult play types, it was interesting to separate out that social play. All of them can benefit from social play. All of the play types can be done socially, and all of them have versions that are free play or not free play, but then still try to look at like, how do we play? And like how can we organize them so that we can start to see it and talk about it more? That was fun and interesting and different than how children play. And I think also different from this idea of like our inner child. I don’t want people necessarily to tap into their inner child and and expect to play like that. I want people to tap into your inner you now and play like that. Find where your play is now. And maybe it relates to how you played as a child, but it’s probably changed a bit and what you needed then and how play served you then is going to be different than how play can serve you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:33] Now that makes so much sense to me. Somebody is listening or joining or watching us in this conversation. They’re kind of nodding along. They’re like, yeah, I get this. Like, it makes sense. And I want to actually see if I can bring some more of this into my life. What’s a sort of, um, what’s an easy first step in.

Cas Holman: [00:45:49] I think, releasing judgment? Please do not judge yourself. If you’re not, if you don’t think you’re playful. Right? I’m also like, I’m aware that people that this is not another thing that you have to now be good at, right. Like, oh, God, now I’m supposed to play on top of everything else, like the kids and the things like, no, this is not. Or like now I have to find time or clear time for this, like maybe. And also no, on your way to to work, on your way to, to, um, picking up kids like, the grocery store, like, while you’re cooking, let yourself, you know, kind of embrace the possibility of a new route, like look up from your phone and people watch and remember that, like, people are really interesting. Fascinating in fact. And look with curiosity and you will be entertained most likely. And the same can be said for nature, like nature is pretty cool and the world we live in is actually there’s a lot there to play with in your imagination, with your attention. And so I think, like the habit of escaping are present world into a digital world, right? Or like I just need to like I need to get out of here. Right? We like, go into our devices when I’m scrolling social media on occasion, I’m like, wait, wait, what am I looking for? Why am I in here? Instead of being out here in this actual world with these actual humans that live near me? I think that’s a good step. Releasing judgment and letting yourself be wherever you are and look up from your phone. And if you’re the only one doing it, release the judgment that that’s weird and that people are gonna think you’re weird because you’re looking around or like, oh, you must not be important because you’re not answering emails all day.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:29] I’ve done that in a coffee shop. I’ll sometimes do that as an exercise and like I’ll just stand there waiting. And with that and intentionally with my phone in my pocket and I’m looking around, everyone else is on their devices, and I feel really weird because I’m like, somebody’s going to look up and be like, what’s up with him?

Cas Holman: [00:47:45] Right? And in fact, you are the same way.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:47] It is a weirdest feeling. Yeah, it is bizarre. It’s like, no, I’m just really trying to pay attention to what’s in front of me. Um, I know it’s weird, but, hey, I’m going to roll with it. Um, yeah. It feels like a good place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up.

Cas Holman: [00:48:07] To make decisions and find purpose that gives you meaning?

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:15] Hmm. Thank you. Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode, safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Debbie Millman about designing a life through creativity and story. You can find a link to that episode in the show. Notes for this episode of Good Life Project. was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by, Alejandro Ramirez, and Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music, and of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring, chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor, a seven-second favor, and share it with just one person. I mean, if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too, but just one person even then, invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter, because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time. I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.